In 1972, Air Force test pilot Lt. Col. Charlie Duke celebrated the service’s 25th birthday nearly alone and far from home in unfamiliar territory.

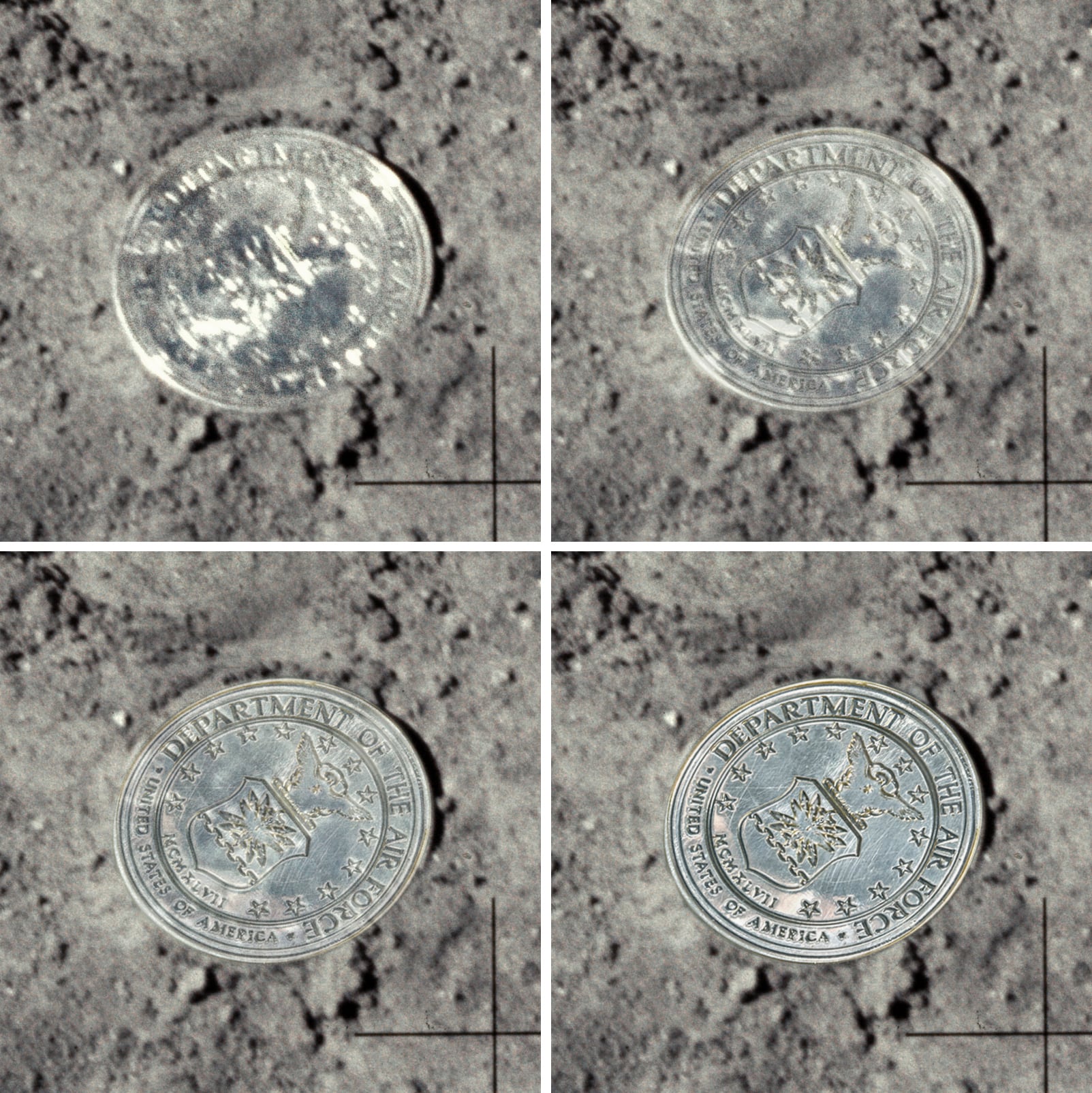

He placed a specially engraved coin on the dusty ground, large and silver and embossed with the Air Force seal, along with other mementos that reminded him of America.

“A special salute from me to the United States Air Force on their silver anniversary this year, from one of the boys in blue that’s pretty far out right now,” said Duke, according to a contemporaneous transcript.

Duke, an Apollo 16 astronaut, was sending his regards from the moon.

The Air Force medallion is thought to remain in the same spot 50 years later, as another milestone approaches and the Space Force begins to carry on the Air Force’s legacy in the cosmos.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of Apollo 16 — the penultimate moon landing by American astronauts in the Apollo era — in the same year as the Air Force turns 75.

Andy Saunders, a space hobbyist-turned-NASA imagery expert, is unveiling new high-resolution photos from Duke’s visit to coincide with Apollo 16′s half-century anniversary. They are part of his forthcoming book of restored NASA images, “Apollo Remastered,” due out in September.

“A lot of the images of these incredibly historic moments are actually really poorly represented, even on NASA’s website,” Saunders recently told Air Force Times.

Photos from the Apollo missions were taken on analog film, which can make images too grainy when enlarged online. To create crisp remastered images, Saunders takes extremely high-resolution scans of that film — which NASA stores in a freezer in Houston — then layers the images with frames from the originals to make the details pop.

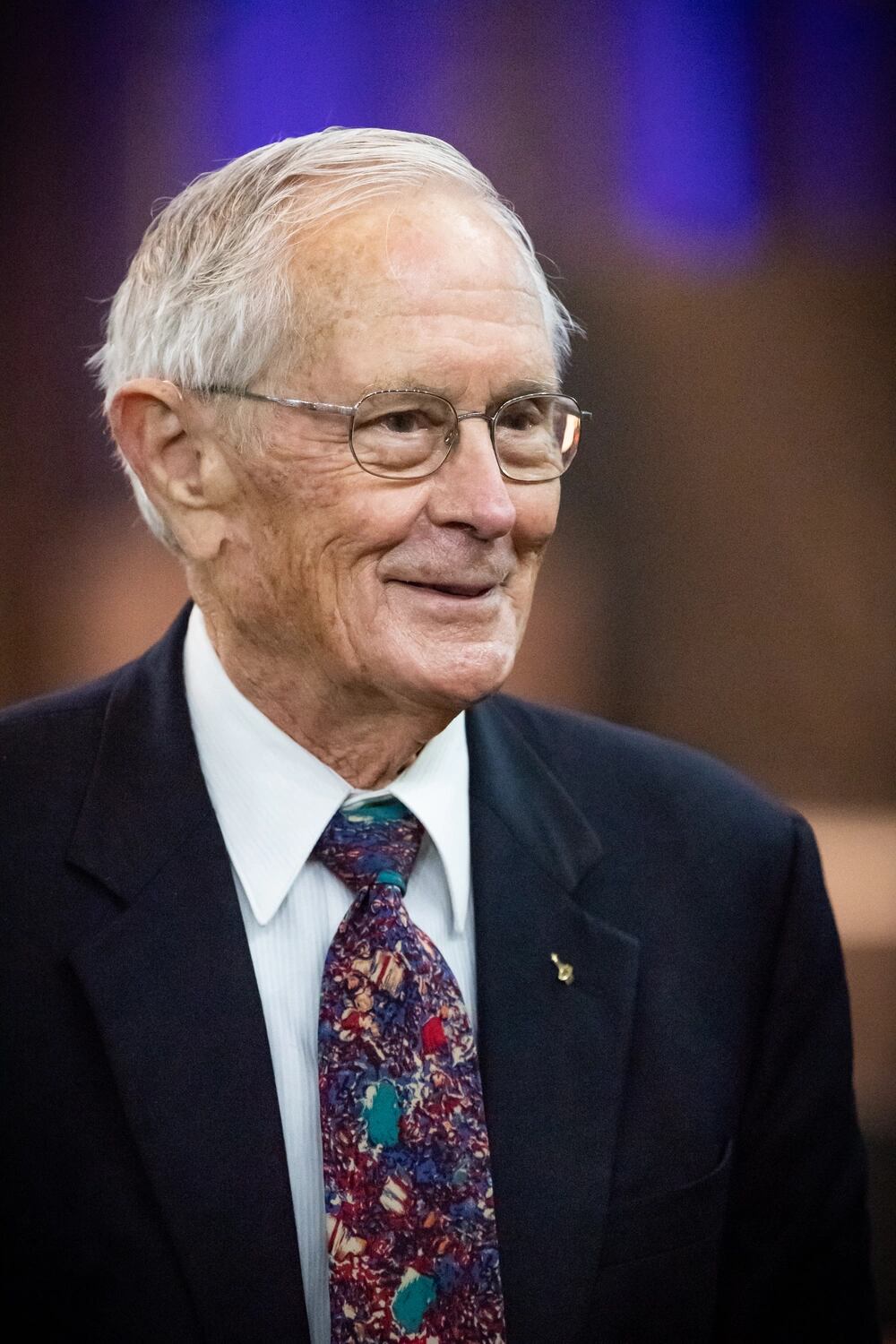

Duke, now 86, was the 10th of just 12 astronauts to set foot on the moon, and the youngest to do so at age 36. He piloted the lunar module on Apollo 16 and served in supporting roles on four other Apollo missions.

“It was a tremendously exciting adventure,” Duke told Air Force Times in an April 13 interview.

He is a 1957 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, where he fell in love not with ships, but with airplanes. His few rides in the N3N-3 “Yellow Peril” biplane at Annapolis sparked a desire to fly, and he transferred into the Air Force to begin flight school.

Duke completed his first solo flight in late September 1957, getting one step closer to his goal of becoming a fighter pilot. But the space race was about to catch up with him.

Less than a month later — on Oct. 4, 1957 — the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite in space.

The United States created NASA one year later and picked the first American astronauts. At the time, Duke was serving in the 526th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Germany’s Ramstein Air Base. He hadn’t yet begun to dream about a new kind of flight.

Then in 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space; the U.S. followed by launching Navy Cmdr. Alan Shepard on his own suborbital flight. President John F. Kennedy followed up that achievement by announcing the plan to put an American on the moon by the end of 1969.

Duke met astronauts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology while studying for his master’s degree in aeronautics. Their enthusiasm convinced him to pursue a spot as a military test pilot — the breeding ground for many astronauts of that era.

He took on the challenge as part of Class 64-C, or “64-Charlie,” and graduated in 1965. Col. Chuck Yeager, the first man to break the sound barrier and head of the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at the time, encouraged Duke to stay on as an instructor pilot.

When NASA put out a call for new astronauts, Duke found that he fit the bill. NASA selected him as part of its fifth group of 19 astronauts in 1966.

The 12 men who formed Class 64-C had particularly good luck with the jump to spaceflight: four headed to space and three walked on or orbited the moon, Duke said. So they created a souvenir — a piece of spacesuit fabric with “64-C” scrawled on it — that would travel with them as a reminder of where they started.

“The 64-Charlie little beta cloth made it on a number of flights,” Duke said, including to the moon and as part of the space shuttle program.

When it came time for Apollo 16 in April 1972, Duke realized that year marked the 25th anniversary of the Air Force’s founding. He was slated to be the only Air Force officer to fly into space that year, too.

“I got hold of the Air Force up at the Pentagon and started talking to the chief of staff’s office,” Duke recalled. “I said, ‘I want to do a ‘Happy birthday, U.S. Air Force’ while I’m on the moon,’ and they thought that was a great idea.”

Apollo 16 launched on April 16, 1972; its three-man crew touched down at the moon’s Descartes highlands four days later on April 20. It would prove to be the United States’ second-to-last moon landing of the first space race.

NASA notes that Navy Cmdr. John Young, the mission commander, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Ken Mattingly and Duke “drove more than 16 miles over three moonwalks on the Lunar Roving Vehicle” and collected more than 200 pounds of rock and soil samples in their 71 hours on the surface.

Duke left tokens behind as well.

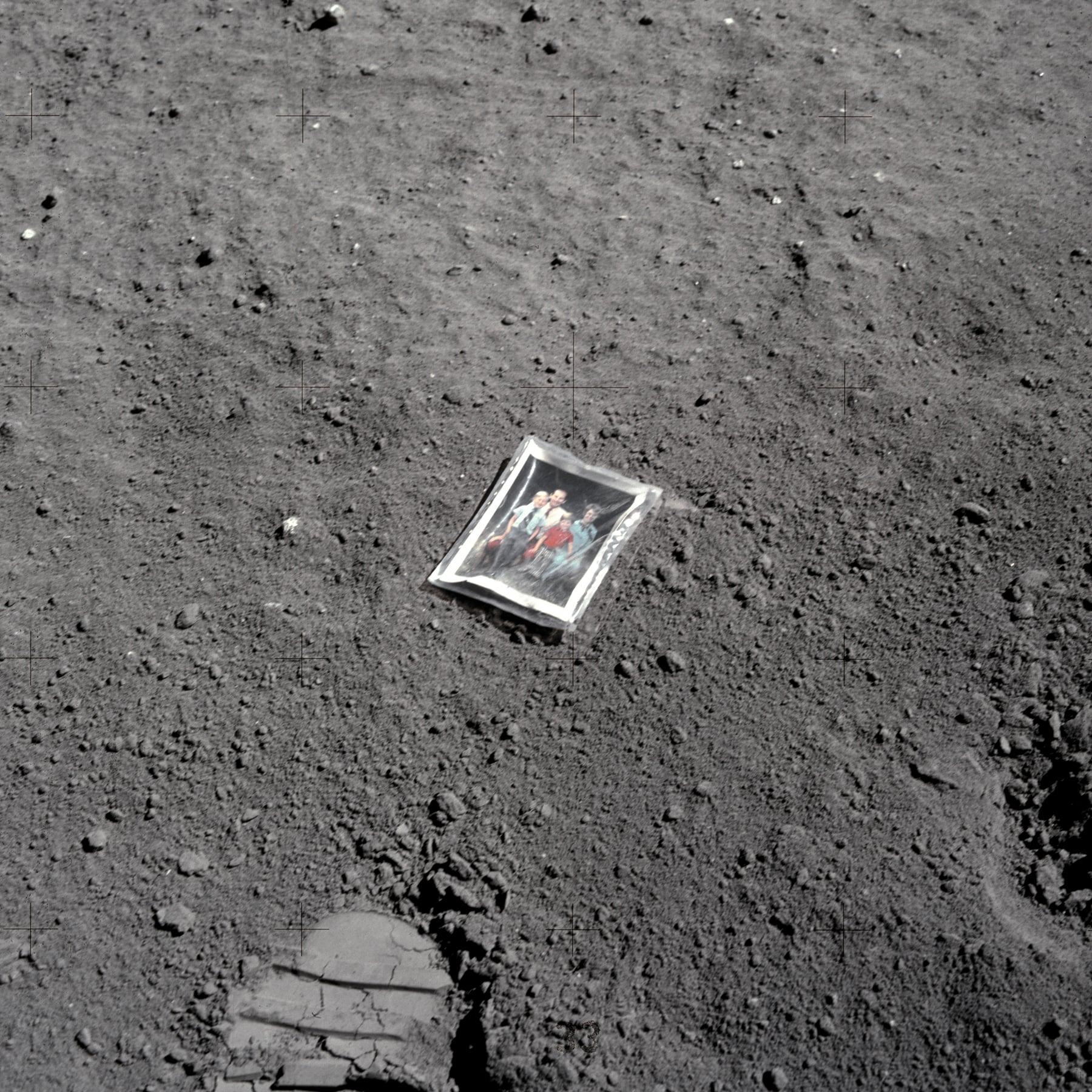

In advance of his trip, the Air Force had minted two silver coins with its official seal to commemorate the service’s 25th anniversary. Duke took both to the moon, plus the 64-Charlie cloth, a miniature flag and a snapshot of his family.

“Hey, Tony,” he said to the spacecraft communicator in Houston from the moon, according to a NASA transcript of the mission. “Is Stu [Roosa] around? … Tell him 64-Charlie just topped the Mount Whitney event.”

Duke later said he was referring to their test pilot school class’s trip to the top of Mount Whitney in California.

He laid one coin and the family photograph on the moon’s surface, where they likely remain today.

“You can see exactly where it landed and then bounced,” Saunders said of the coin that remains on the moon. “You see a huge amount of detail in the photographs.”

Saunders noted that radiation from space would have crinkled up and faded the picture, but he plans to send a small copy of the photo back to the moon in a more resilient capsule on a commercial lunar mission at the end of the year.

Duke brought the other coin, the flag and a moon rock back to the Air Force. Those items now reside in the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Though Duke took a picture of the test pilot class memento in space, he said he doesn’t recall whether he left it there.

Saunders believes the cloth is still on the surface, though likely not in its original spot because of its lighter weight. He expects the coin will last millions of years, however, even with micrometeorite strikes.

No one knows exactly where the artifacts are, but they are thought to sit near where the lunar module was parked, he added.

“It certainly brings it alive with the definition that these pictures have,” Duke said. “To be the only Air Force officer to have a chance to say happy birthday from the moon was very, very special for me.”

The airman-turned-astronaut spent about two decades on active duty and reached the rank of colonel before joining the Air Force Reserve in 1976. He worked in training and recruiting and flew T-38s before retiring near the 30-year mark as a brigadier general.

He has logged almost 266 hours in space and 4,150 hours in aircraft.

Duke is also known for serving as a spacecraft communicator, or CAPCOM, on the Apollo 11 mission that saw Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin plant the first human footsteps on the moon in 1969.

He prepared for his own possible trip to the moon as part of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission in 1970, but was famously sidelined from the backup crew when he caught the measles from his son.

“It all worked out,” Duke said. “Mattingly came back on our [Apollo 16] crew and we became good friends and worked really wonderfully together.”

As the United States prepares to return to the moon and beyond, Duke is excited for what he sees as a natural next step in space exploration.

He believes the commercial spaceflight boom will lead to a division of roles: NASA can focus on deep space exploration with its Artemis missions to the moon and then to Mars, while private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin can handle military, civilian and tourist work closer to Earth.

“I see a lot of big cooperation with near space and I’m very excited about the commercialization of space,” he said. “It’s going to result in, I think, some really, really big breakthroughs.”

When Duke looks at the moon now, he sees his own “object reached … with a sense of satisfaction and pride.”

“A small-town boy from South Carolina getting to go to the moon was never even a dream of mine,” he said. “Yet it happened.”

This story was updated April 23 at 6:07 p.m. to correct the year NASA was founded. It was 1958, the year after Sputnik launched.

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.