Sitting in his Pentagon office in the twilight of a nearly 44-year career, Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Larry Spencer's mind flashed back to a lonely road in Korea on the way to a town called Yechon.

That's where his father, Alfonzo Spencer, an Army heavy equipment operator transporting a bulldozer, either fell off or dove off to evade enemy fire during the Korean War. Alfonzo Spencer's left hand got caught in the bulldozer's gears and was mauled. Nobody knew he was there, and he slipped into a coma for days while gangrene set in — and nearly took his life.

But that wasn't the end of Alfonzo Spencer. And the tenacity he showed would eventually inspire his eldest son, Larry, to constantly push himself to excel — first enlisting in the Air Force, then studying for his college degree at night and on weekends, earning his commission as an Air Force officer, and climbing the ranks until he became a four-star general — a fairly rare occurrence for a prior-enlisted airman — and the vice chief of staff of the Air Force.

Spencer never forgot his enlisted origins. Decades later, he still speaks highly of two chief master sergeants who mentored him and encouraged him to get his commission. And he said his time as an enlisted man helped shape his leadership style by reminding him how important enlisted airmen are.

"I feel fortunate that I was able to start off as a one-striper," Spencer said in a July 22 interview. "The Air Force mission gets done by the enlisted force, and we have the best enlisted force in the world. That shapes everything I do."

As the Air Force's second-highest ranking officer, Spencer oversees the Air Staff and helps Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh organize, train and equip the 664,000 total force airmen. He also serves on the Joint Chiefs of Staff requirements oversight council and deputy advisory working group.

Spencer previously served as the Joint Staff's director of force structure, resources and assessments, and was the first Air Force officer to be assistant chief of staff in the White House military office in the mid-1990s.

In a March address outlining her plans to increase diversity in the Air Force, Secretary Deborah Lee James held Spencer up as an example of the untapped potential contained among enlisted airmen, and why the Air Force needs to give them more opportunities to earn their commissions.

"How many more potential Larry Spencers do we have out there, who are in our enlisted corps?" James said.

And on June 29, James unveiled a new Gen. Larry O. Spencer Innovation Award, to honor him for his efforts to push the Air Force to cultivate new ideas from airmen on how the service can do things better. Spencer said working on programs such as Make Every Dollar Count and Airmen Powered By Innovation were some of his greatest accomplishments.

Spencer also pointed to his work on sexual assault prevention and response as another key accomplishment.

Spencer married his wife, Ora, in 1974, and they have two sons and a daughter: Larry, Derrick and Shannon.

Spencer's last day before going on terminal leave for his retirement will be Aug. 7. The following week, he will become the new president of the Air Force Association.

Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Larry Spencer never forgot his enlisted origins. Decades later, he still speaks highly of two chief master sergeants who mentored him and encouraged him to get his commission.

Photo Credit: File

Inherited work ethic

These days, Spencer said, wounded warriors commonly continue serving for years after sustaining traumatic injuries. In his father's day, however, losing a limb typically meant the end of one's career. But Alfonzo Spencer was not the type to give up easily, his son said.

During his several-day coma, Alfonzo Spencer had a dream about chopping a tree down for firewood on the Red House, Virginia, farm where he grew up.

"He came to the point where he needed one more swing to fell the tree, and he decided, for whatever reason, he didn't want to," Spencer said. "He laid the ax down, and at that point is when he woke up from his coma."

Alfonzo Spencer was rescued and taken to Japan, where his mangled hand was amputated and he spent time in an iron lung to pull him back from the brink of death.

After returning home from Korea, Alfonzo Spencer was stationed at the former Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he helped develop and test prosthetics — and where Larry Spencer was born in 1954. His father wore a hook that he opened and closed using wires strung through a hole in his bicep, and the expert marksman requalified using a rifle modified to work with that hook.

Spencer said his father instilled discipline in his six children. The Spencers lived in what he described as "a fairly rough, old neighborhood" in Southeast Washington D.C., but they had the nicest house around, because his father saw to it that young Larry was out mowing the lawn and performing other maintenance.

"He had a tremendous work ethic," Spencer said. "I didn't like it back then; I appreciate it now. We weren't allowed to go hang out at night like my friends. They would tease me all the time because I had to go back in the house when the streetlights came on. I had to do my homework, I was in Boy Scouts. Trust me, walking through a D.C. neighborhood in a Boy Scout uniform was not a cool thing to do."

After graduating high school, Spencer played linebacker and offensive guard for a semipro football team in Washington — everybody played iron man football in those days, he said — and worked a summer job for the Census Bureau in Suitland, Maryland.

Spencer loved football, and played it with ferocity that drew attention from college coaches. He recalled one game where he delivered a bone-crushing hit on an opposing player during a kickoff return, which made the other player so mad they started tussling on the field before resuming play. After the game, Spencer saw that player storming across the field with a tire iron in his hand, so he and his teammates quickly got on the bus and peeled out of there.

"I just laid him out, because I just love that kind of contact," Spencer said with a laugh. "He didn't appreciate it at all."

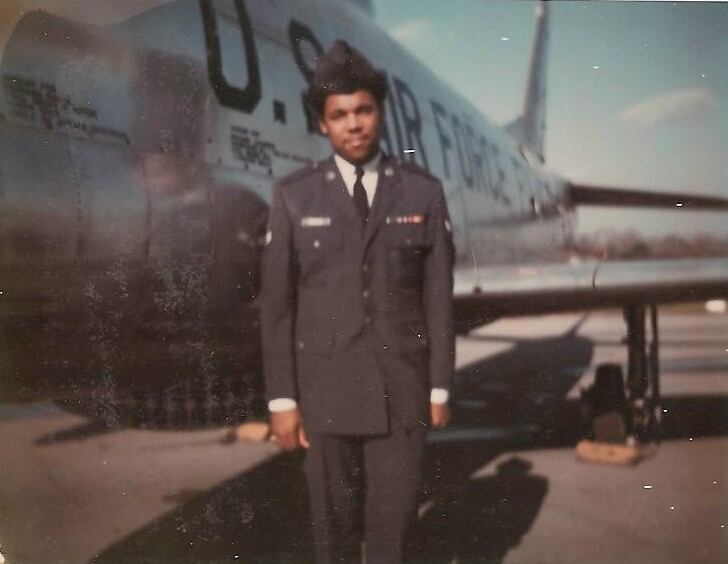

Larry Spencer as a young airman.

Photo Credit: Air Force

Air Force is the answer

But Spencer didn't know what he was going to do with his life. One day in 1971, he went to the mall in Suitland on a whim and wandered into a recruiting office. By the time he walked out, he had signed up for the Air Force.

Spencer said the Vietnam War may have been part of what motivated him. People kept telling him if he had to join the military, it was best to go Air Force and not end up on the ground as part of the Army or Marine Corps.

But Spencer said his father's example may have also influenced him, if only subconsciously.

"I always appreciated the way he carried himself, the way he was disciplined, the way he seemed different from a lot of the other people in the neighborhood," Spencer said. "He was really well-respected because he was in the military. Without being mean, he taught us things. We had to work. We couldn't just sit around the house watching TV. And I think there was something missing [in his life] that I didn't know what it was. That sort of helped me get on track. I didn't really know where I was going. Obviously, playing semipro football, there's not much future in that."

Spencer's first job was in admin, and he enjoyed the Air Force. But things were different in the '70s, he said. After a short stint at Pope Air Force Base in North Carolina, he was assigned to Taiwan, where he and his friends made a bet to see how long they could go without cutting their hair. Spencer won — he grew a gigantic Afro, and made it through the entire year's tour without being caught by a noncommissioned officer with a nose for regulations.

"It was huge," Spencer said of his hair. "We packed it down with a stocking cap at night ... because it had gotten so out of control. My wife would braid my hair on the weekends. Keep in mind, I didn't stand out. Everybody was trying to get away with what they could get away with, in terms of the grooming standards."

Spencer's Afro days were numbered once he returned to the States for an assignment to Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, working for Strategic Air Command.

"That was a no-nonsense, you-stick-by-the-rules, kind of command," he said.

Spencer, by this point an airman 1st class, said that a chief master sergeant walked by his office one day, noticed his unruly hair, "moonwalked back, and was just absolutely shocked" and chewed Spencer out.

"He took me to the barber shop, paid the barber, sat me in the chair and watched me get my hair cut," Spencer said. "To his credit, he never said anything to my boss. And he became a mentor of mine after that."

Path to college, OTS

That chief helped set Spencer on the path to getting his college degree. Spencer's enlistment was almost up and Clemson University offered him a scholarship to play football. But Spencer had a wife and two sons by that point, and while the chance to play ball again was enticing, he didn't know how he would provide for them.

So he passed up Clemson and instead re-enlisted, and promised himself by the time his second enlistment was up, he would have a degree.

"From that point forward, I bore down on college like you would not believe," Spencer said. "It was tough."

He returned to Pope and started taking classes every weekend from Southern Illinois University professors who were flown in specifically to teach troops. He also took elective classes at local schools three days a week.

He got his bachelor's degree in industrial engineering technology from Southern Illinois in 1979, and another chief encouraged him to try for Officer Training School, and helped him get in. He became a distinguished graduate of OTS and got his second lieutenant bars in February 1980.

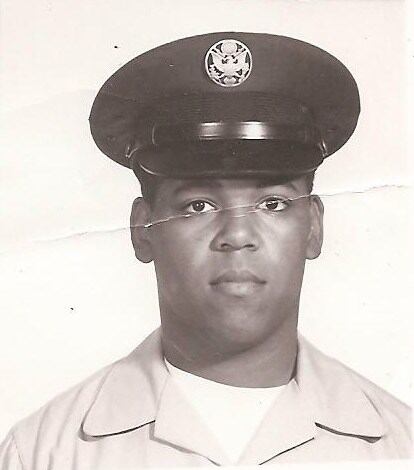

Larry Spencer as a young airman.

Photo Credit: Air Force

Today's Air Force

Spencer said that he's seen the Air Force take great strides in improving its diversity and racial tolerance during his career. When he joined, he said, the Air Force had never had a black four-star general, or a black officer serving as budget director, which is a two-star position. He occasionally heard racial slurs directed his way. One day, while playing at a park on Robins Air Force Base in Georgia, Spencer said his 6-year-old son overheard another parent use a racial slur to describe him.

But that kind of talk was already uncommon in his younger days, Spencer said, and is virtually unheard today. More women and minorities hold leadership roles, reflecting the nation's demographic shift.

"I think the military is adjusting to the new demographics that we have," Spencer said. "In terms of diversity, we still have a lot of work to do, but we have made tremendous progress."

Today, having reached the top of the Air Force, Spencer felt it was important to keep looking out for younger airmen, the way those chiefs helped him decades ago when he was finding his way — and also listening to their ideas. Spencer held regular Web chats with young airmen between the age of 18 and 24, focusing on issues such as how to stop sexual assault and the Make Every Dollar Count campaign to collect their money-saving ideas.

He also held focus groups and invited young airmen into his office to have lunch with him. He said these conversations with young enlisted airmen helped him gather some unique and unexpected perspectives on issues such as potential changes to basic allowance for housing, retirement systems and commissaries.

"Everything I do and everything I recommend to the chief and the secretary is through that lens, of how is this going to help our enlisted force," Spencer said. "We sort of assume sometimes that they don't want things to change, but when you talk to them, they are actually a lot more open to change than the senior leaders are sometimes."

One of the most pressing issues for Spencer lately is how to stop sexual assault in the Air Force, and setting up bystander intervention programs to stop assaults from happening. He said that his conversations with young airmen have helped him understand that they need a more candid and open discussion with their commanders about what is going on with sexual assault, and what is holding back prevention efforts.

More than four decades after Spencer joined the Air Force, it's nearly an entirely different organization. At the tail end of the Vietnam War, the service communicated through typewriters and color-coded carbon copies, and the best intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance available was a still camera mounted on a low-flying F-4. Today, the Air Force uses supercomputers and drones to spy on — and sometimes drop missiles on — adversaries half a world away.

"We've come a tremendous way, just in my career," Spencer said. "The technology that we have now, compared to the technology we had when I came in, is astronomical. What I challenge folks today is, you need to think about what the Air Force is going to look like when you get ready to retire. Because it's going to be nothing like it is now."

But Spencer said he always wished he could have gotten out of the Pentagon more and spent more time with airmen out in the field.

"It's just such an enlightening and motivating and exhilarating experience to be out amongst airmen and see how good they are, how motivated they are, to be able to talk to them," Spencer said. "I can't tell you the number of airmen that come up to me — it's pretty close to every day. 'I heard you enlisted, how did you get commissioned?' 'Will you give me a letter of recommendation?' I try to encourage them. I would do more of that if I could."

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.