Less than five years after he'd played a critical role in desegregating the defense industry, A. Philip Randolph joined other civil rights leaders in a meeting with the president of the United States … and let him have it.

"I said, 'Mr. President, the Negroes are in the mood not to bear arms for the country unless Jim Crow in the Armed Forces is abolished,'" Randolph recalled telling Harry Truman.

The president was less than pleased with the assessment, Randolph said in a 1968 oral history housed by the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library. That didn't stop Randolph from pressing forward.

"The Negroes, Mr. President, have never had a fair break in the Armed Forces," he told the president. "This isn't anything new. Not only have they not had a fair break, but they have been the objects of affront and insult all over this country; and we have fought and bled in every war, but they have not gotten adequate recognition and consideration."

The president's reply, as Randolph recalled it: "Well, what do you want done?"

It may seem like an atypical reply for the leader of a superpower to give to anyone, but Randolph's stature in the civil rights landscape by 1948 made it understandable.

DELIVERING A MESSAGE

Three decades earlier, he'd launched The Messenger, which billed itself as "The only radical Negro magazine in America." He and his publication opposed U.S. involvement in World War I while railing against a segregated military and defense industry. His views led to his arrest under the Espionage Act; charges were later dropped, according to his New York Times obituary.

In 1925, Randolph founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and began what would be a dozen-year quest to secure a labor agreement with the Pullman Company. Randolph and his organization would survive threats, accusations of Communist ties and other attacks from management until the deal was done in 1937.

The group's position in the African-American community extended far beyond that of a typical union. Members would deliver copies of The Chicago Defender, keystone of the African-American press at the time, well beyond city limits. Randolph's message of desegregation became more than a workplace matter – especially as another world war loomed.

The U.S. defense industry joined the fight in Europe before American military units did. But while gains in that sector had created jobs and revitalized economic indicators, segregation prevented those benefits from reaching all sectors of the population.

Randolph and others wanted that changed. His idea, which he brought to President Franklin Roosevelt in early 1941, was to organize a march on Washington.

"… [H]e told me definitely that he didn't want a march on Washington because it would end up in violence and bloodshed and no doubt some people might get killed," Randolph recalled in the oral history. "And he said if a precedent such as that were to be established, it would simply stimulate other groups to plan marches on Washington and there would be no end to it. And he wouldn't be able to control it."

The argument didn't sway Randolph, who wanted an executive order desegregating the defense industry. He recalled inviting Roosevelt to speak at the march, even requesting the War Department provide tents for the protesters. The president declined.

Randolph set a July 1 date for the march, and crowd estimates soon crept into the tens of thousands, or larger. Roosevelt installed Fiorello LaGuardia, then-mayor of New York City, as an intermediary of sorts, putting him in charge of a committee to address the matter. The mayor eventually would advocate for an executive order, and Randolph recalled a committee member reading him a draft.

A. Philip Randolph, foreground, testifies before the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 1948. He told the panel that millions of blacks would refuse to register to serve under draft and military training unless racial segregation and discrimination are ended.

Photo Credit: AP photo

There was a problem.

"It doesn't apply to the federal government," Randolph recalled pointing out. "They said, 'Well, you can't apply this to the federal government. The federal government is above everything.' I said, 'But the federal government is guilty, too, of discrimination against Negroes as far as jobs are concerned.' And he said, 'Well, now you're going to throw this whole thing into the fire.'"

Out of the fire would emerge Executive Order 8802, signed June 25, 1941, in which Roosevelt would, in part, "reaffirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin. …"

The "or government" part is in Roosevelt's handwriting, not typed. Randolph called off the march.

MILITARY DESEGREGATION

While defense industry workers, at least in theory, wouldn't suffer discrimination, service members spent World War II in segregated units. As Truman made his push for a peacetime military draft, one that would take form as the Selective Service Act of 1948, Randolph and other civil rights leaders lodged their concerns and levied their accusations of mistreatment by the military of black service members.

So, what did Randolph want done?

"I said, 'Well, some action ought to be taken in the form of an Executive Order barring and banning Jim Crow in the Armed Forces, eliminating discrimination and segregation,' " Randolph recalled in the oral history. "He says, 'I agree with you.'"

But the military draft law went through without any desegregation language, and Randolph set about organizing civil disobedience across the country, asking African-Americans not to register for the draft.

On July 26, 1948, Executive Order 9981 would take effect. The same day, according to the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, anonymous Army staff officers told the press that the order didn't mean the service would be forced to integrate its units. Truman clarified the intent days later at a news conference, but Randolph didn't call off plans for resisting the draft law until August.

Despite the early stumble, "there were definite changes that took place in the Armed Forces," Randolph said in the oral history. "Negroes began moving into everything, various areas, and so forth. The young Negroes began going into the army, in larger numbers because there was some security involved and there was opportunity for promotion."

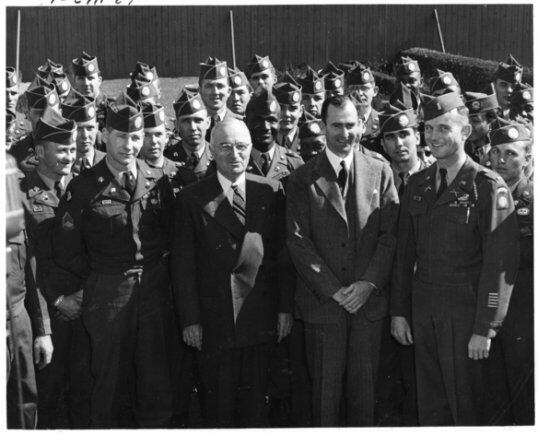

President Harry S. Truman and Army Secretary Frank Pace Jr. pose with members of the integrated 82nd Airborne Division on Feb. 27, 1951, at the White House Rose Garden. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 in 1948.

ONE MORE MARCH

As integration moved forward in the military and began in fits and starts around the nation, Randolph had nearly completed his transition from young, jailed firebrand to elder statesman. Once under fire for advocating socialism, a Truman Library document from presidential adviser David Niles in 1948 labels Randolph as "not a left-winger" and one of a group of "pretty conservative Negroes."

But he wasn't done meeting with presidents. Randolph led the organization of what would become the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, doing so with direct input from President Kennedy, who initially lobbied for it not to take place. While some doubted whether Randolph would've been able to muster 100,000 for his threatened 1941 march, most estimates put the 1963 event – which included Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech – at 250,000 marchers.

Randolph and Bayard Rustin, a fellow established civil rights leader and march co-organizer, would read a list of the march's demands after King's speech, asking for, among other items, the desegregation of all school districts, comprehensive federal civil rights legislation and a federal aid program to train displaced workers of all races.

Randolph would step down from the union he founded in 1968. He died in 1979 at age 90. There are statues honoring him in both Boston and Washington, D.C. – both in train stations.

Kevin Lilley is the features editor of Military Times.