On December 25, 1944 – Christmas Day – Cpl. James Baldwin and the 784th Tank Battalion landed in Soissons, France, to fight in the Allied liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe.

The 19-year-old Baldwin, of tiny Wagram, North Carolina, had entered the service two years earlier through the U.S. Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which was created “to ensure a continuous flow of technically and professionally trained men” for the war effort. He had qualified for the program by achieving high marks on the Army General Classification Test, but when the program was suspended, Baldwin found himself in the regular army and headed into combat.

As Baldwin and the 784th rolled through the forests of France to confront the German war machine, they were attached to the 35th Infantry Division (Wagonwheel Division).

But unlike most armored and infantry battalions, the 784th was unique – it was a segregated battalion. Its soldiers, Baldwin included, were black.

Now, 75 years later, a new research project aims to illuminate the forgotten history and legacy of the “Black Liberators” of the Netherlands and the 172 black soldiers who remain buried there today.

Revisiting history’s forgotten soldiers

A decade ago, in anticipation of the 65th anniversary, Mieke Kirkels led a research effort in the Netherlands to compile oral histories from the war, including from Dutch farmers who lived under Nazi occupation. Through them, Kirkels heard accounts of black service members who had labored tirelessly to transport and bury the dead at temporary collection points and field cemeteries.

These sites would become the Netherlands American Cemetery at Margraten.

Soon after, researchers located Jefferson Wiggins, a sharecropper’s son who joined the Army at the age of 16 to escape the Jim Crow South and the terror of the Ku Klux Klan. As a first sergeant, Wiggins served with the 960th Quartermaster Service Company (QSC). He later received a battlefield commission to become a second lieutenant from Gen. George S. Patton himself.

Along with hundreds of other black soldiers, Wiggins was tasked with burying nearly 20,000 soldiers killed in action during the ongoing battles for liberation. Digging graves in the middle of winter, these men labored in 12-hour shifts for three months straight, according to Wiggins’ account.

The segregated units of the QSC received sub-optimal housing and poor hardware, adding to the trauma of working with maimed and frozen bodies. Like many black soldiers who manned transportation routes, Wiggins’ company was tasked with ferrying the corpses of their fellow yet segregated soldiers from the front to makeshift, wartime cemeteries.

With limited resources and harsh conditions, Wiggins and his fellow soldiers attempted to add a small amount of dignity to the burials, conducting “makeshift services” with prayers and hymns from home, according to his account.

But their stories were largely forgotten, divided among the memories of those who served, the lore of living family members, and the partially destroyed war records in the archives.

When Dutch researchers located Wiggins, he had already written two books about his experiences in a segregated military, been awarded a Meritorious Unit Commendation in 2007 and delivered the graduation ceremony keynote address at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 2009.

That year, he returned to Margraten, Netherlands, for the first time since the war, the place where he worked digging graves and burying corpses.

“We had been commanded to give respect to those we could not even associate with in life,” Wiggins said during the visit. “But on that first day, we realized that whatever life experiences we’d had as African Americans, this was our obligation - to set aside our prejudices, our colors, and our fears, and give to these young Americans the honor, the respect, and the dignity they so well deserved.”

Wiggins, who went on to receive an honorary doctorate, died in 2013, shortly before his story – and those of his fellow black soldiers – was memorialized in Mieke Kirkels’ book, “From Alabama to Margraten: Memories of Grave Digger Jefferson Wiggins.”

Kirkels later expanded her research to document the stories of the children of Dutch women and black GIs in “Children of Black Liberators.”

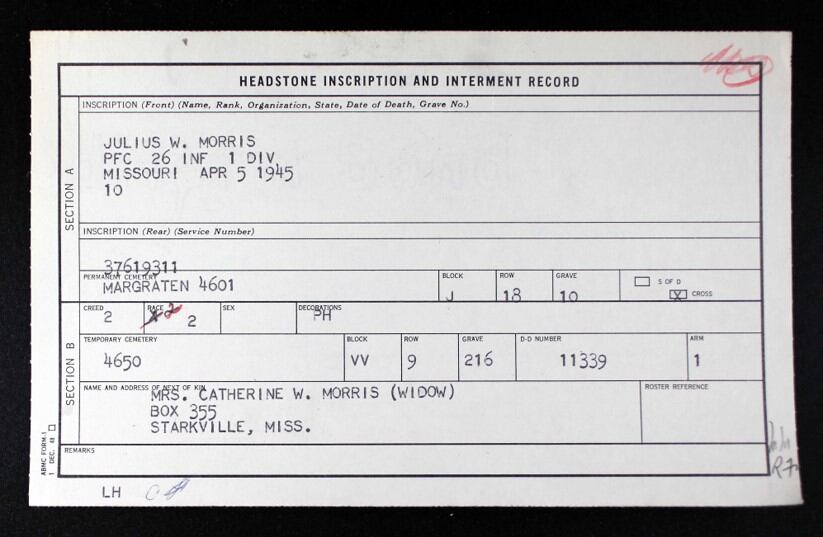

Wiggins was not alone, however, in his quest for recognition of the black liberators, and researchers began to explore the lives of the 172 black soldiers buried in Margraten, among their 8,000 additional white compatriots.

The Black Liberators Project was born with the goal of capturing the experiences of the living veterans and highlighting the memories of the 172 fallen, partly through reconnecting with their descendants.

Documenting the Netherlands’ Black Liberators

On a rainy afternoon last Thursday near Embassy Row in Northwest Washington, D.C., Cpl. James Baldwin entered the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Donning his “World War II Veteran” hat and a row of service medals on his Army jacket, the now 96-year-old Baldwin sat in the front row as researchers presented their findings. Baldwin recounted his story of serving in a segregated military and liberating the Netherlands.

“December 25, 1944: that’s when we had our first baptism of violence,” Baldwin said. “We wanted to go in to prove that we [African Americans] could fight.”

At the time, the prevailing stereotype was that most black service members should be sidelined in noncombat roles. Baldwin said the 784th had white officers, who often favored the unit’s white infantrymen over the black tank drivers and crewmen.

“I said, ‘I’m black and they’re white. We are going to fight the same enemy. Why the difference?’” Baldwin added.

“Segregation pervaded every aspect of African American soldiers’ experiences in World War II,” said Dr. Tyler Bamford, Leventhal Research Fellow at the National World War II Museum. “More than one million African Americans served in the Armed Forces, yet they could not even use the same facilities as white soldiers, even on military bases.”

For black soldiers, many of the freedoms they were fighting and dying to protect in foreign countries were not afforded to them at home. To protest this hypocrisy, and push for the end of segregation and discrimination, leaders in the black community announced the “Double V Campaign” in the Pittsburgh Courier, “the most influential black newspaper in the country.” The campaign sought victory against foreign enemies abroad and victory against prejudice and racism at home.

Still, black soldiers faced routine discrimination in the segregated military.

“The Army believed white southerners were best qualified to command black troops by virtue of their experience growing up in the segregated South,” said Bamford. “In practice, many white officers resented the assignment and took opportunities to denigrate and abuse African American soldiers.”

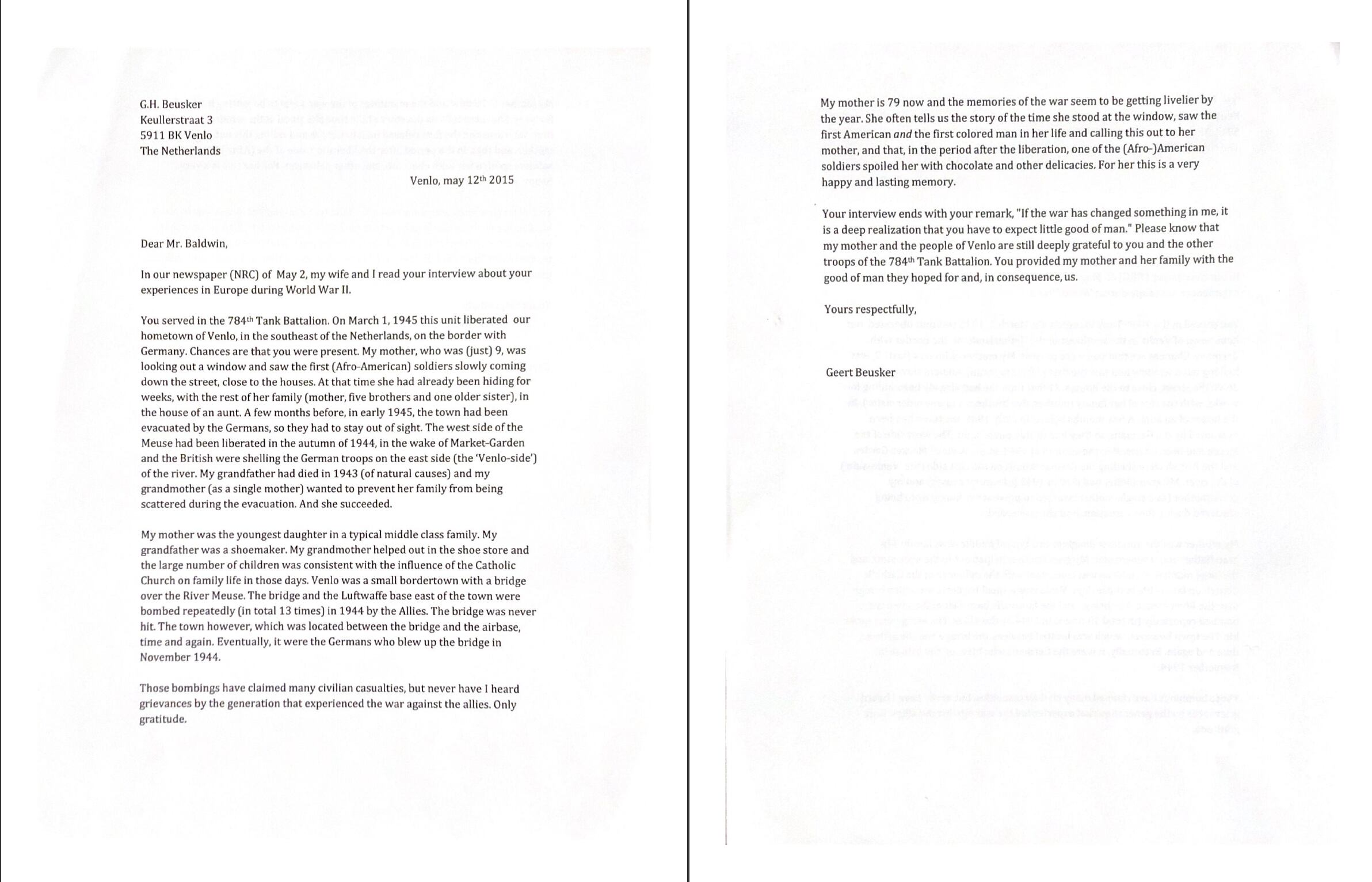

The segregated tank battalions, however, did enter combat. According to the U.S. Army Center of Military History, on March 1, 1945, the 784th Tank Battalion joined a task force that “moved so swiftly that the enemy, surprised,” was quickly overwhelmed and defeated. The task force had captured 20 towns and villages and rolled into Venlo, Netherlands, liberating the city.

Another black armored battalion, the 761st Tank Battalion, also participated in the liberation of Europe, including the Netherlands. This unit entered combat in November 1944, and consisted of six white officers, 30 black officers and nearly 700 enlisted black soldiers. The battalion fought at Bastogne, Belgium, as part of the famed Battle of the Bulge, before liberating several Dutch towns on the German border.

“This is for many an unknown story, now told,” said Air Commodore Paul Herber, Dutch defense attaché, at the event. “Research has shown that contributions of African American soldiers were unjustly overlooked by history. Through these new collaborations, we have corrected that oversight.”

The research was headed by Sebastiaan Vonk and Maarten Vleeming in the Netherlands, who soon connected with American researchers Myra Miller, team leader at Footsteps Researchers, and Ric Murphy, vice president of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society.

Vonk and Vleeming began with personnel files at the 65.5-acre Netherlands American Cemetery at Margraten. Filtering by “race codes” for the deceased, the pair located records for the 172 black soldiers. Then, they reached out to their American counterparts, traveled to the World War II archives in Missouri and dug through thousands of boxes of fire-tinged personnel records. (A massive fire in 1973 destroyed 80 percent of U.S. Army records from 1912 to 1960).

Through local chapters of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, the team began crowd-sourcing stories about the deceased, utilizing census records, oral histories and family documents.

“When we talk about World War II, we often hear about it was a fight for democracy, for freedom. But when you look at those black soldiers, they were told to go overseas and fight for freedom that they didn’t enjoy at home,” Vonk said. “I felt it was important to bring it out. These men made very vital contributions to the war effort.”

“We have an opportunity to give proper recognition to their service and sacrifice. What we are doing here in part is correcting our military history, our history of the Netherlands," Vonk added.

Completing family history

For Murphy, the lack of emphasis in historical discussions of the service and deaths of the “Black Liberators” demonstrates a larger trend of downplaying the sacrifice of black military veterans.

“The perception is that [African Americans] tend not to look for our ancestors because we think they are not in the files,” Murphy said. “Our ancestors are there, and we are finding our ancestors are speaking to us and saying, ‘Come find me.’”

For many veterans of the war – black or white – retelling stories of their service was not easy.

“It’s the things they don’t want to think about. They want to come back to normalcy,” Murphy said. “It’s not unusual for any soldier of war to come back and not share stories.”

Add to this fact the tradition of oral storytelling and lost records, and it makes recreating these men’s lives difficult.

“One of the things we encourage people to do is ask questions of their family members,” said Hannah Scruggs, a public historian at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “We ask family members who have seen truly horrific things and don’t want to share, to please write them down. It’s so important to have these stories recorded, to continue to share these stories.”

Despite these difficulties, many families members have tried to reconnect with their loved one’s service. Now, the Black Liberators Project means the service and sacrifice of the 172 black soldiers will become a permanent piece of their family’s history.

LaVonne Taliaferro-Bunch, whose great uncle, Lenwood Taliaferro, is buried in Margraten, shared that her grandfather had traveled around Europe decades earlier searching for his brother’s final resting place.

“I think it’s important for my family because my grandfather talked to us about the rich history [of service]. When you see people substantiating some of the stories he told me...it’s important,” said Taliaferro-Bunch. "To see this [project], to me, adds closure for him.”

“We talk about the struggles that we’ve had in this country, but we also struggled to liberate peoples around the world. That makes us global citizens,” Taliaferro added.

And for Cpl. James Baldwin, he, too, has received recognition, 75 years later. At the embassy on Thursday, Baldwin received a certificate of appreciation from the Dutch people for his contribution to their liberation. For his 100th birthday, Baldwin plans to visit Margraten to see his old friends one last time.

Dylan Gresik is a reporting intern for Military Times through Northwestern University's Journalism Residency program.