As a young African-American officer, Larry Spencer regularly sought out career advice from black senior officers. All too often, the message he received was unsettling.

"Every one of them told me the same thing: 'I don't like telling you this, and it's not right,' but they felt like they had to work harder than their peers to get to the same point," Spencer, the former vice chief of staff, said in a Feb. 16 interview. "I just accepted that. Maybe I shouldn't have, but I did. I do feel like I really had to work harder sometimes."

The advice, unpleasant as it may have been, served him well. Spencer ultimately earned promotion to four-star general and appointment as the service's second in command, where he served three years until retiring last year.

But despite his considerable success, Spencer remains concerned about the lack of diversity at the top of the force, and roadblocks minority airmen may encounter.

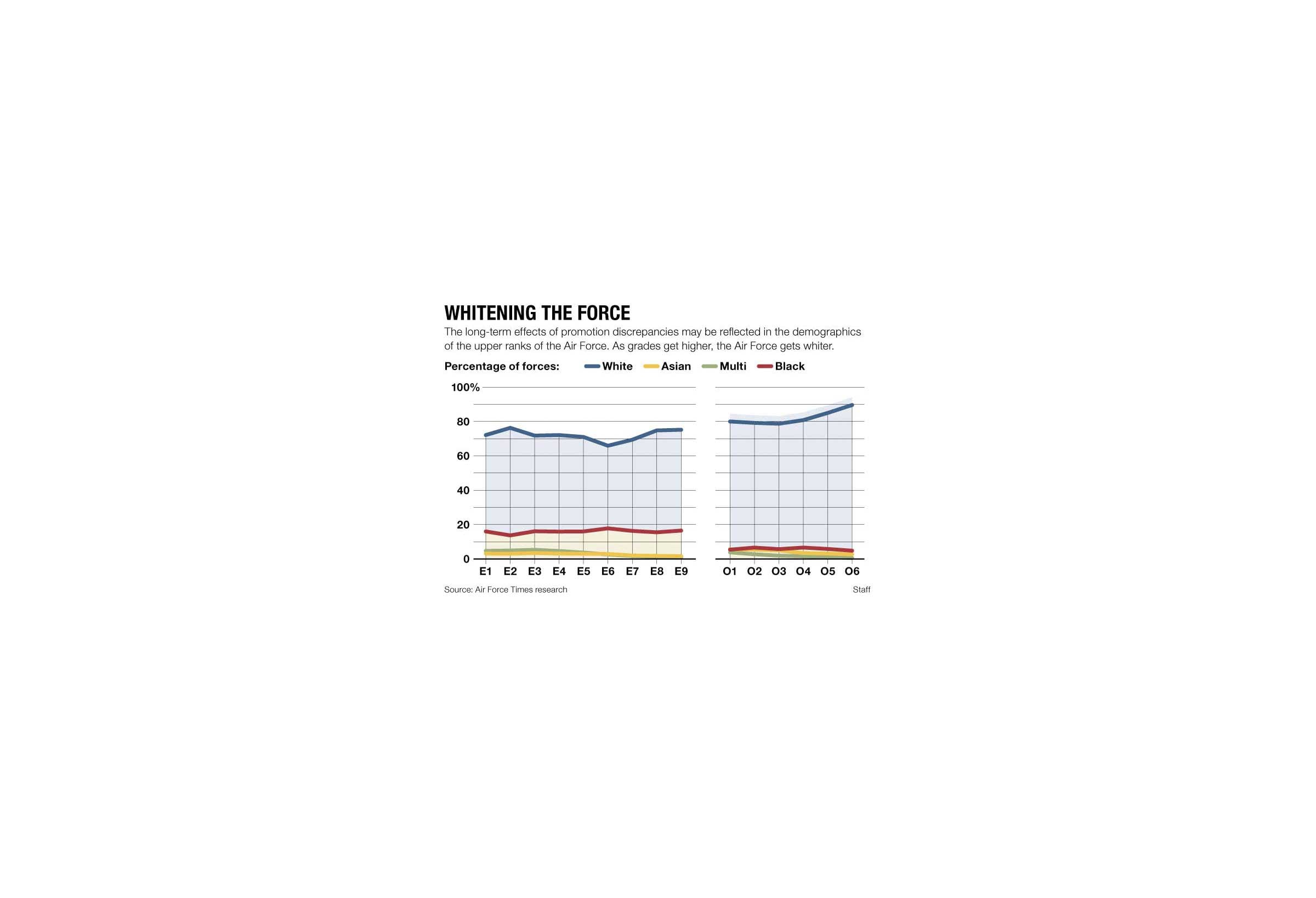

Six years of statistics on promotions and selection rates analyzed by Air Force Times indicate that if you're a minority, your odds of being tapped for promotion — especially to the most senior officer and enlisted ranks — are not as good as they are for white airmen.

And experts believe that these disparities contribute to a gradual — but noticeable — whitening of the Air Force as airmen progress higher up the ranks. As one looks at the top senior non-commissioned officer and general officer ranks, it becomes harder and harder to find faces of color.

In a Feb. 18 interview, Brig. Gen. Brian Kelly, director of military force management policy, said the Air Force saw similar patterns as Air Force Times when it analyzed promotion trends.

"It's not necessarily a straight conclusion to say, this is a promotion board issue, because there's a bigger context to it," Kelly said. "It's about development, it's about recruiting, it's about retention, it's about jobs and opportunities people get. And for us as a whole, looking at, how do we maximize the talent that's available to us in the United States and make sure we have the best talent in the Air Force."

Air Force Times research

Photo Credit: Staff

The data provided by the Air Force include promotion percentages by rank and race but does not break that down into promotions by branches or specialty codes. Nevertheless, the data make it clear that white airmen in all grades consistently have enjoyed higher selection rates than airmen who are of Asian descent, black, or multi-racial.

Much of that, experts believe, owes to a longstanding practice of minorities being overrepresented in administrative and support assignments as opposed to combat and technical specialties that often provide greater promotion rates. Minorities for generations have joined the military at a time when they had limited career options, or to gain basic job skills that would make them more employable in a civilian society that otherwise made it difficult for them to join the workforce.

Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James has made improving the service's diversity a key goal of her tenure.

"Diversity and inclusion will help us to become more strategically agile in our Air Force," James said during a major address last March, in which she announced a panel of nine initiatives she hoped would increase opportunities for women and minorities. James was unavailable to comment on this story.

Those initiatives included launching a new and revamped online mentor-matching program last July, which was called the Career Path Tool and is now called MyVector, setting diversity and inclusion requirements for career field development team chairs, and sending a memorandum of instruction to promotion boards asking members "to find officers who have demonstrated they will nurture and lead in a diverse and inclusive Air Force culture."

The racial gap in Air Force promotions is not hard to identify. Look, for example, at the 2015 Line of the Air Force lieutenant colonel's board. That year, 1,027 white in-the-zone officers were selected for O-5 out of 1,416 eligible, for a selection rate of 73.2 percent. That is far higher than the 63.8 percent selection rate for black majors who were up for promotion last year, the 67.5 percent selection rate for officers of Asian descent, and the 47.6 percent selection rate for multi-racial officers.

Brig. Gen. Brian Kelly

Photo Credit: Air Force Times staff file

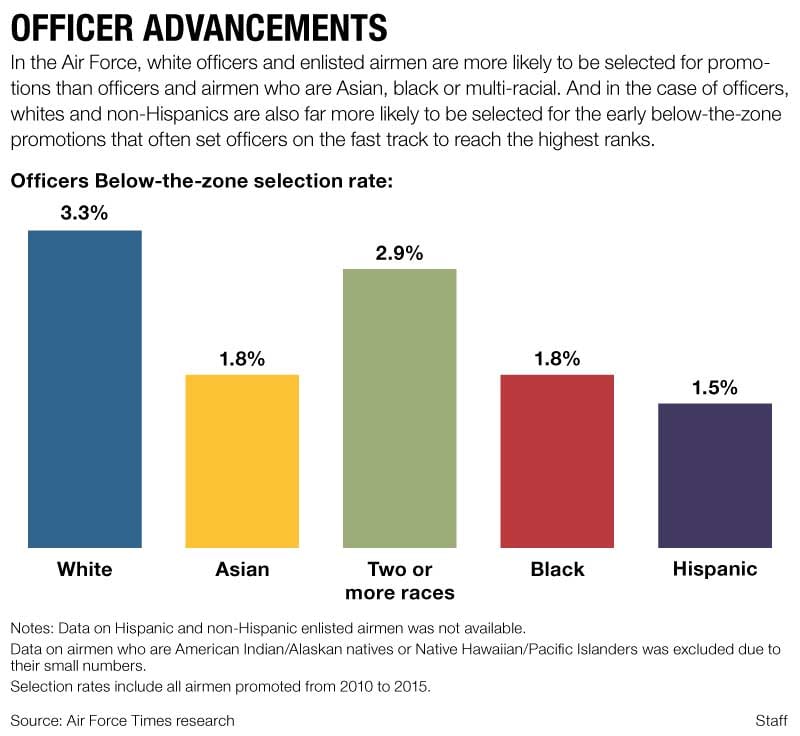

While some of that owes to more whites being concentrated in jobs with better promotion opportunities, and vice versa, data show that whites are also being tapped at greater rates for fast-track careers: They are far more likely to be picked for the early below-the-zone promotions, a crucial factor in filling some of the top jobs in the Air Force.

From 2010 to 2015, overall, 3.3 percent of white officers eligible for a below-the-zone promotion were selected to advance — twice the 1.8 percent selection rate for both Asian and black officers, and still better than the 2.9 percent selection rate for multiracial officers.

Air Force Times Research

Photo Credit: Staff

When statistics for all officer promotion boards in all years going back to 2010 are combined, an overall picture of the disparities emerges. Data shows that 80.7 percent of eligible white officers were selected for in-the-zone promotions, as opposed to 79.3 percent of Asian officers, 78.8 percent of multiracial officers, and 72.3 percent of black officers.

Below-zone selection rates matter a great deal, Spencer said — because it shapes the Air Force's top leadership for years to come. "Below-the-zone is where, probably 99.9 percent of the time, general officers come from," he said. "Those are your future general officers. That's when the Air Force, as a system, starts breaking out superstars who have the greatest potential. There's a lot that goes into that. Obviously potential and talent goes into it, but also mentoring and the ratings you get and those type of things."

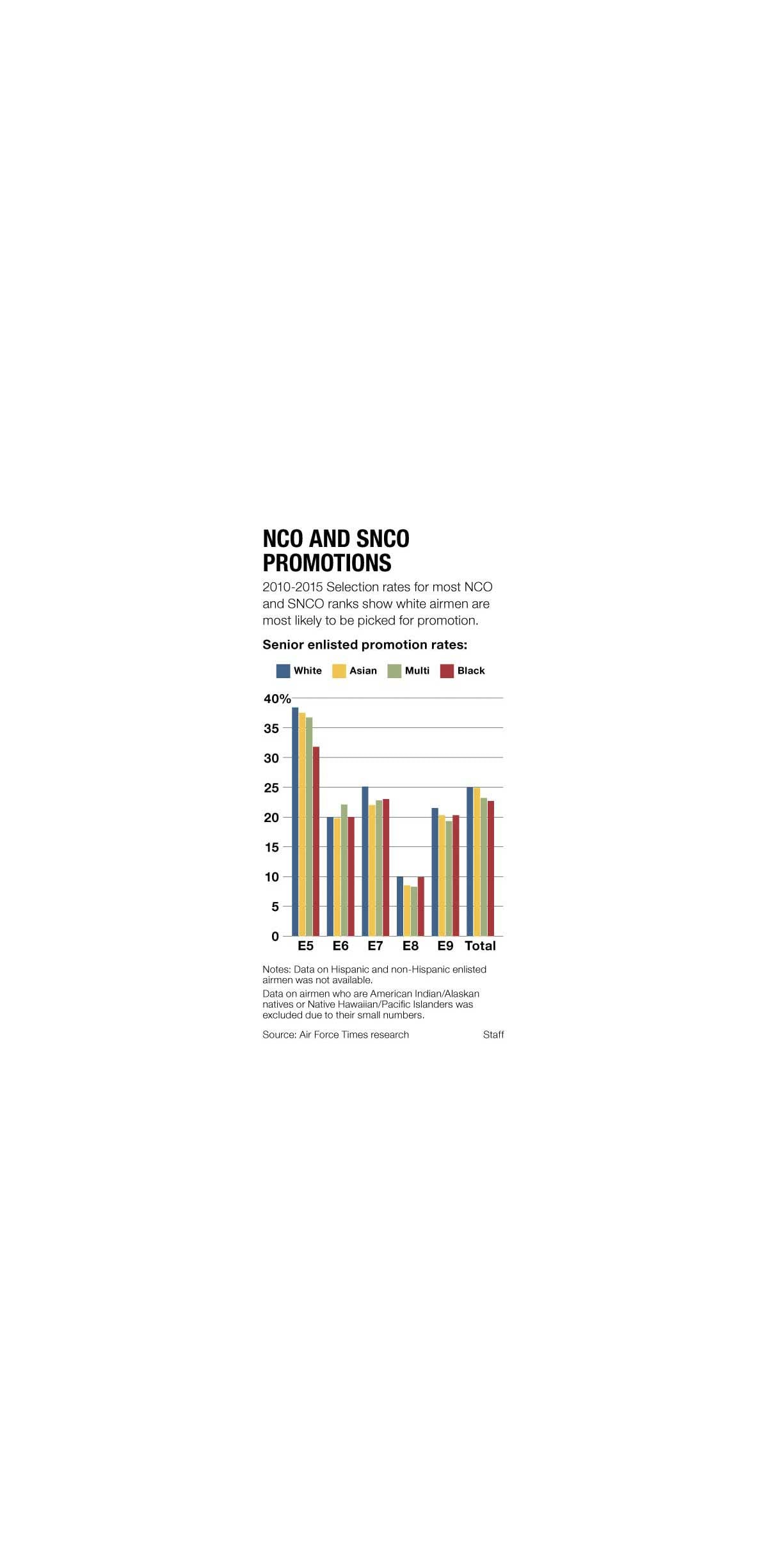

When it comes to enlisted airmen, the patterns are not as consistent, but still noticeable. Selection rates for white enlisted airmen were higher than members of other races who were up for promotion to staff sergeant, master sergeant and chief master sergeant. For technical sergeant, multi-racial airmen had higher selection rates than white and black airmen, and for senior master sergeant, white and black airmen had similar selection rates. But when all grades were taken into account, white enlisted airmen had the highest selection rates of all, slightly above Asian airmen.

Air Force Times research

Photo Credit: Staff

All of which suggests that, while the Air Force is trying to make strides on improving its diversity, it still has a way to go. "This is a very complex issue," Spencer said.

The problem isn't that the promotion board process is inherently biased, but that the pipeline for promotion under existing Air Force practices puts minorities as a disadvantage,said Nelson Lim, a researcher and social scientist at the RAND Corporation who co-authored a 2014 study titled "Improving Demographic Diversity in the U.S. Air Force Officer Corps." In fact, he said, officers in operational roles have the advantage — and most of them are white.

The RAND study found that, when minority and female officers were compared to white male officers with nearly identical records, they were promoted at the same rate, 93 percent of the time. That suggested that "systematic bias is not present in the Air Force's promotion system," the report said.

But getting minority officers to the same point as white officers is far trickier.

Spencer said that officers who take operational roles — that is, pilots — tend to be the ones who get promoted to colonel and above, and get picked for the plum leadership jobs in the Air Force. Indeed, all but three of the service's current 11 four-star generals are pilots.

Furthermore, 25 of its 40 or so three-star generals — nearly two-thirds — are pilots. The remaining three-star billets are scattered among navigators, flight surgeons, lawyers, engineers, personnelists, contractors, logistical officers or space officers.

But often, Spencer said that minority officers don't tend to go into pilot career fields, and instead find themselves in support jobs.

"When you look around the Air Force at the [major command] commanders or the senior commanders, they're all wearing wings," Spencer said. "I'm not saying that's a bad thing. But if you start out with a lower percentage of minorities who are wearing wings, then that's the way that's going to end up. That in and of itself is a problem."

This places them at a disadvantage — one that is only exacerbated over time, Lim said. For example, the report said that for an unknown reason, minority groups in the Air Force are less likely to have early markers of career success such as high Air Force Academy order of merit scores than their white counterparts.

Officers with high order of merit scores are often those chosen to attend Squadron Officer School in-residence, the report said, which helps them get distinctions such as being named distinguished graduate, which leads to those officers getting a boost when promotion time comes around.

This is the accumulated advantage phenomenon of the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, Lim said. "As you gain momentum in your career, you get traction, and you get assignments and you've got different achievements, you are put into a different path. And whether you are on that path or not can be determined relatively young. And so you got this halo effect that consistently has an impact."

And sometimes, Spencer said, unconscious bias or pressure may play a role that limits minority officers' ability to get ahead. Spencer said that years ago, when he was a colonel, a two-star general asked him what he wanted his next assignment to be. Spencer asked to be the military assistant to the next secretary of the Air Force. But because the rumored top candidate was black, the two-star said that wouldn't work.

"It won't look right for a black secretary to hire a black military assistant," Spencer said he was told. "I looked at him, and I said, as a colonel can say to a two-star, 'But white secretaries hire white military assistants all the time. Why is that not a problem?' His only answer was, that's different."

Spencer said he talked to many senior black officers in the Air Force over the years who felt pressure to not hire assistants who look like them, fearing that it would look like favoritism. He said top women leaders in the Air Force face the same pressure.

"It is something that you have to think about, which is a different experience if you are not in the majority," Spencer said. None of the services has ever had a minority in the top job, but several have appointed minorities to the number two spot.

But fixing the problem is bound to be far more difficult — and will need to be tackled on multiple fronts.

The RAND study co-authored by Lim concluded that the Air Force needs to take a closer look at its recruiting processes. Not only does the service need to recruit from minority populations, but it needs to make sure the minority candidates it recruits are highly qualified. This could include changing the mix of schools with Reserve Officer Training Corps detachments, and possibly moving ROTC detachments to more-selective schools, the study said. The Air Force could also change the mix of high schools the academy recruits from.

Spencer said before he retired, he personally met with several members of the Congressional Black Caucus to persuade them to increase their sponsorship of minority cadets to the academy, and said they are doing so.

The Air Force also needs to step up its mentoring of young minority airmen, he said.

And Spencer also thinks the Air Force needs to rethink its image of an ideal leader, and broaden it to include officers who aren't rated pilots.

"Who said that senior positions need to be held by those that are operators?" Spencer said. "Obviously a lot of them do, but why do so many of them need to be? That's always been a little bit controversial."

Spencer also said that as new minority airmen come in, the Air Force needs to do more to encourage them to consider piloting, as well as other fields such as space and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

But convincing them might be easier said than done.

Spencer — who grew up in Southeast Washington, D.C. — is concerned that when he speaks to young black men in junior high and high schools, he's not seeing a lot of interest in the military.

"When I speak to inner city schools here in D.C., especially a lot of young males, when I ask them what they want to be, the answer is the same," Spencer said. "They want to be the next LeBron James, or they want to be the next Dr. Dre or the next Jay-Z. There's nothing else in between."

Even when he talked to minority students who were interested in the military, Spencer was surprised to find they weren't even thinking about becoming pilots.

Spencer said that during a mentorship opportunity last year, he visited schools in D.C. and Baltimore, speaking to young, smart minority students who were interested in engineering. They were spellbound as he showed them pictures and movies of F-22s and F-35s.

But afterward, he asked them how many wanted to fly.

"I got no hands," Spencer said. "They all wanted to come into the Air Force, they wanted to be engineers, they wanted to go into finance. But as impressed as they were with flying, they didn't want to do it. Which I just found fascinating. Here are bright students who could come in and be chief of staff someday, just were not at all interested in flying."

And the same was true when Spencer was growing up, he said. He never saw a pilot — Air Force or otherwise — who was black when he was young.

"I couldn't even dream of that," Spencer said. "I didn't know that even existed."

And today, young white kids can see films depicting white pilots like Maverick and Goose in "Top Gun." But while Hollywood is more diverse these days, similar depictions of minority pilots are still harder to come by. Spencer thinks the implicit message — that flying is not for them — had unconsciously sunk in to those students.

"I can't explain it any other way," Spencer said. "That blew me away. It's dismaying, it's disappointing. But I understand it because I was them, and I wasn't interested either."

Spencer thinks more female and minority officers who are rated pilots need to keep reaching out to young female and minority students, visiting high schools wearing their flight suits, and talking to them about how neat it is to fly an airplane. That way, he said, the kids can see people who look like them have succeeded.

"I can't tell you the number of times I went into inner-city high schools, and people came up to me and said, 'Man, I didn't know they had black generals in the Air Force,'" Spencer said.

Chevy Cleaves, the Air Force's director of diversity and inclusion, largely agreed with Spencer's observations. He said that the overall populace these days is often less aware of military service than it has been in the past, which presents a challenge for all branches of the military. And he said that the challenge may be exacerbated in minority communities.

And the Air Force needs to look at not just mentoring of minority officers, Cleaves said, but also what kind of messages they receive about how the organization of the service works and what career advice they get.

"What you may have then, is a challenge that reinforces itself," Cleaves said. "When we talk about why minorities may select support roles, I think it becomes a more complex conversation in terms of who their mentors were, and what advice was given, and what knowledge base they were working from when they were told, if you were considering the Air Force as a career, they need to understand how that organization works. And operations, however that's defined, will have a strong role at senior levels. I'm not sure those conversations are occurring in the way that we hope they'll occur in the future."

One thing that Spencer and Kelly both agreed should be off the table is imposing diversity quotas guaranteeing minorities receive a certain percentage of promotions.

Not only would that be illegal, Kelly said, "It's not a good way to do business."

Instead, Cleaves said, the Air Force is trying to work more closely with organizations such as the National Society of Black Engineers, the Society of Women Engineers, and the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers to reach out to those communities.

But the Air Force also needs to do a lot more to study how minorities progress through their careers once they don their blues, Cleaves said.

"There's a lot of work that we have to do to understand how talent progresses through the Air Force, and if there are any barriers that need to be addressed, that might impact anyone's experience so that we can ensure that they all have the opportunity to go to the maximum of their potential," Cleaves said. "That is great for them, but it is also great for the Air Force, because of the mission that we all share."

Video interview with Gen. Spencer was conducted at the Air Force Association's Air Warfare Symposium in Orlando, Florida, on Feb. 25.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.