On the first full day of the Tet Offensive, F-100 Super Sabre pilot 1st Lt. “Fearless” Fred Abrams was given a mission like no other.

The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army had sprung multiple, coordinated surprise attacks on U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. The situation was especially dire at Bien Hoa Air Base, where Abrams was stationed with the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron and where Viet Cong forces launched an early morning attack on Jan. 31, 1968.

By the end of the day, Abrams and his flight lead, the late Maj. Joe Bulger, had carried out danger-close airstrikes on the building where the VC had dug in to make their last stand, ending the battle. Abrams said it is believed to be the only time in Air Force history that the service’s fighter jets were scrambled to carry out airstrikes on their own base.

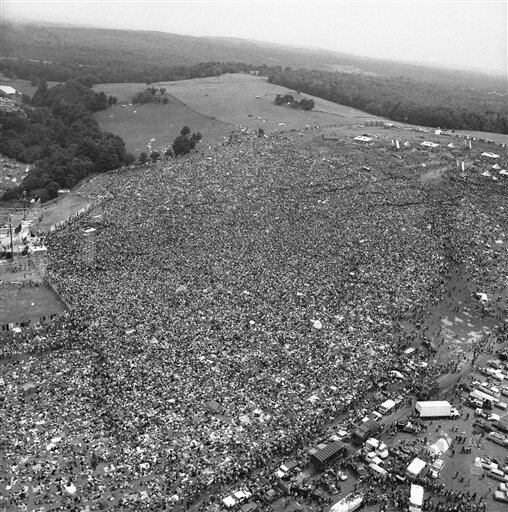

Fifty years later, almost to the very hour, Abrams and other F-100 pilots gathered at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, to commemorate the battle. The event, organized by the Super Sabre Society, took place in the shadow of an F-100 that was stationed at Bien Hoa ― about 16 miles northeast of the city formerly known as Saigon ― during the Tet Offensive, though not one of the two that flew that day. A painting of the F-100 taking off during the battle by renowned aviation artist Keith Ferris was unveiled during the ceremony and added to the Smithsonian’s F-100 display.

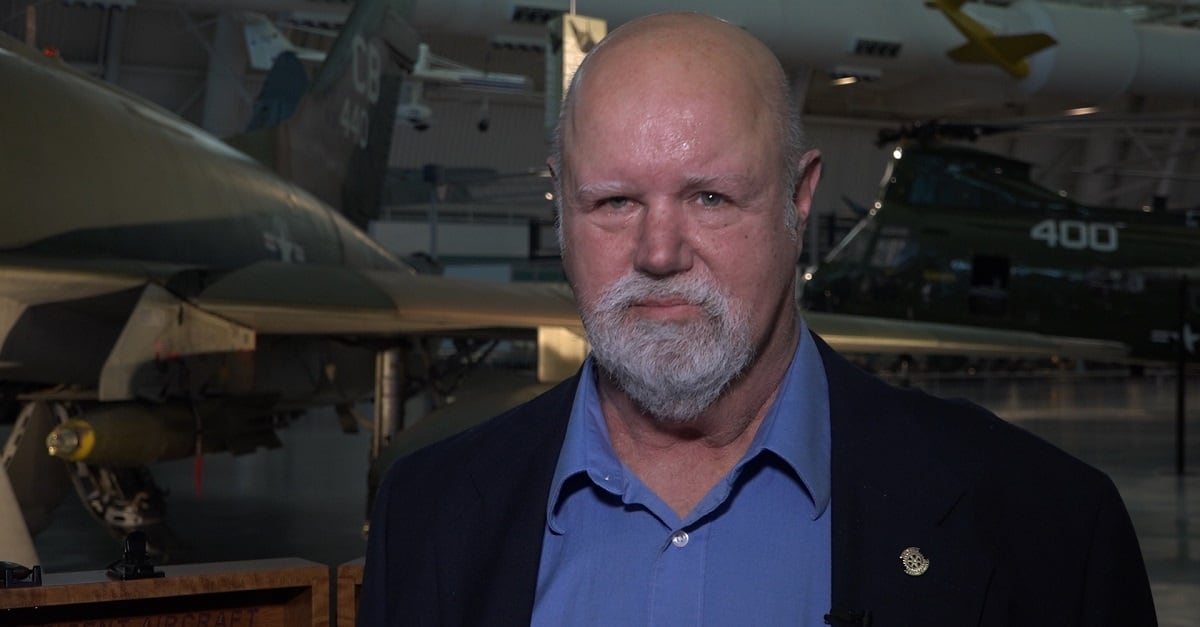

Before the ceremony, Abrams reflected on the extraordinary battle that took place a half-century ago.

The battle began at 3 a.m., when the VC attacked the base. For hours, Air Force security forces and Army troops at Bien Hoa battled the enemy, pushing them back until the Viet Cong established a defensive position in and around a white building on the east end. They were dug in, Abrams said, and no amount of pounding from the Army soldiers and helicopters or security forces could dislodge them. Artillery also wouldn’t work, because the troops were too close to the enemy. So they called in the Super Sabres.

“The whole east end was hot,” Abrams said.

Abrams and Bulger were eager to get in the air, but there was a problem: The VC had already destroyed and burned out a visiting F-4 aircraft on the west end of the runway, littering the strip with shrapnel and debris. And if the Super Sabres kicked up even a single piece of that debris during takeoff, they could be destroyed before they even got off the ground. So they had to wait for hours while the flightline was cleared.

Finally, about 4 p.m., Abrams and Bulger fired up their F-100s and took off through a hail of thick ground gunfire, the likes of which he had never before seen. But that didn’t rattle him.

“You don’t think about it,” he said. “We have an expression called ‘Golden BB’: If they’re gonna hit you, they’re gonna hit you. And if you’re lucky, you make it through and don’t get hit. I’ve been shot up a bunch; I didn’t even take a hit that day.”

But the 101st Airborne troops were so close to the enemy that any airstrike risked killing them, too. Abrams and Bulger circled the area while the soldiers pulled back. Finally, after about an hour and a half, they were ready.

With the guidance of an O-1 Bird Dog spotter aircraft, Abrams and Bulger closed in and made three passes each ― the first to drop napalm, and the second and third to drop 500-pound bombs on the target.

Soon afterward, in a letter to his mother, Abrams wrote that it was the most scared he had ever been ― not for his own safety, but for the troops on the ground. Even though they had pulled back, they remained dangerously close to the target, maybe 50 to 100 yards away.

“I was really puckering,” Abrams said. “If you miss, you’ve just killed your own guys, and that’s about the worst thing you could do. … You think a lot, ‘I can’t make a mistake, I can’t make a mistake.’”

With modern precision-guided munitions still decades away and only “dumb” bombs at their disposal, Abrams and Bulger had to aim incredibly carefully. They flew about 500 miles per hour in a 15-degree dive to release the ordnance about 400 feet off the ground, and had to adjust the projected reticle on the F-100’s sight to take into account how the bomb would drop and drift due to the wind ― all by hand.

“It was the pride of your success at doing it accurately,” Abrams said. “It wasn’t some computer telling you what to do.”

RELATED

But it worked. The strike was a success, and effectively ended the nearly 15-hour siege at Bien Hoa. The final 500-pound bombs set off a secondary explosion in the bunker when a cache of VC munitions ― likely intended to be used on the other F-100s on the flightline ― detonated, he said.

Abrams said he and Bulger marveled at how unbelievable the mission was. And the crew stationed at Bien Hoa were “jubilant” and amazed that for once, they actually got to see the planes they maintained and supported in action, instead of only seeing them fly away and return hours later, shot up and with all their bombs dropped.

Abrams and Bulger both received the Distinguished Flying Cross for their actions that day. In a citation accompanying Abrams’ award, the Air Force commended him for “determination, aggressiveness, and courage” that saved his fellow troops from taking heavy losses, despite the “extremely poor” visibility and approaching darkness in which he flew.

“The professional competence, aerial skill, and devotion to duty displayed by Lieutenant Abrams reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Air Force,” the citation said.

Fifty years later, Abrams’ love for the “gorgeous” F-100 and his excitement for flying it are still apparent. But its effectiveness in its primary mission ― close-air support, backing up the troops on the ground ― was what made him really love the plane. And to Abrams, the strike that broke the siege at Bien Hoa was, in some respects, the ultimate example of the F-100’s ability to carry out that mission.

“It’s incredibly rewarding, because you’re doing what it is you trained to do,” Abrams said. “It feels good to be among other F-100 pilots here today, and standing next to an F-100 that was at Bien Hoa, Jan. 31, ’68. I can’t believe it’s been 50 years.”

RELATED

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.