The readiness of the Air Force’s aircraft fleet is continuing its slow, steady deterioration — and this could spell trouble for the service’s effort to hold on to its pilots and its ability to respond to contingencies around the world.

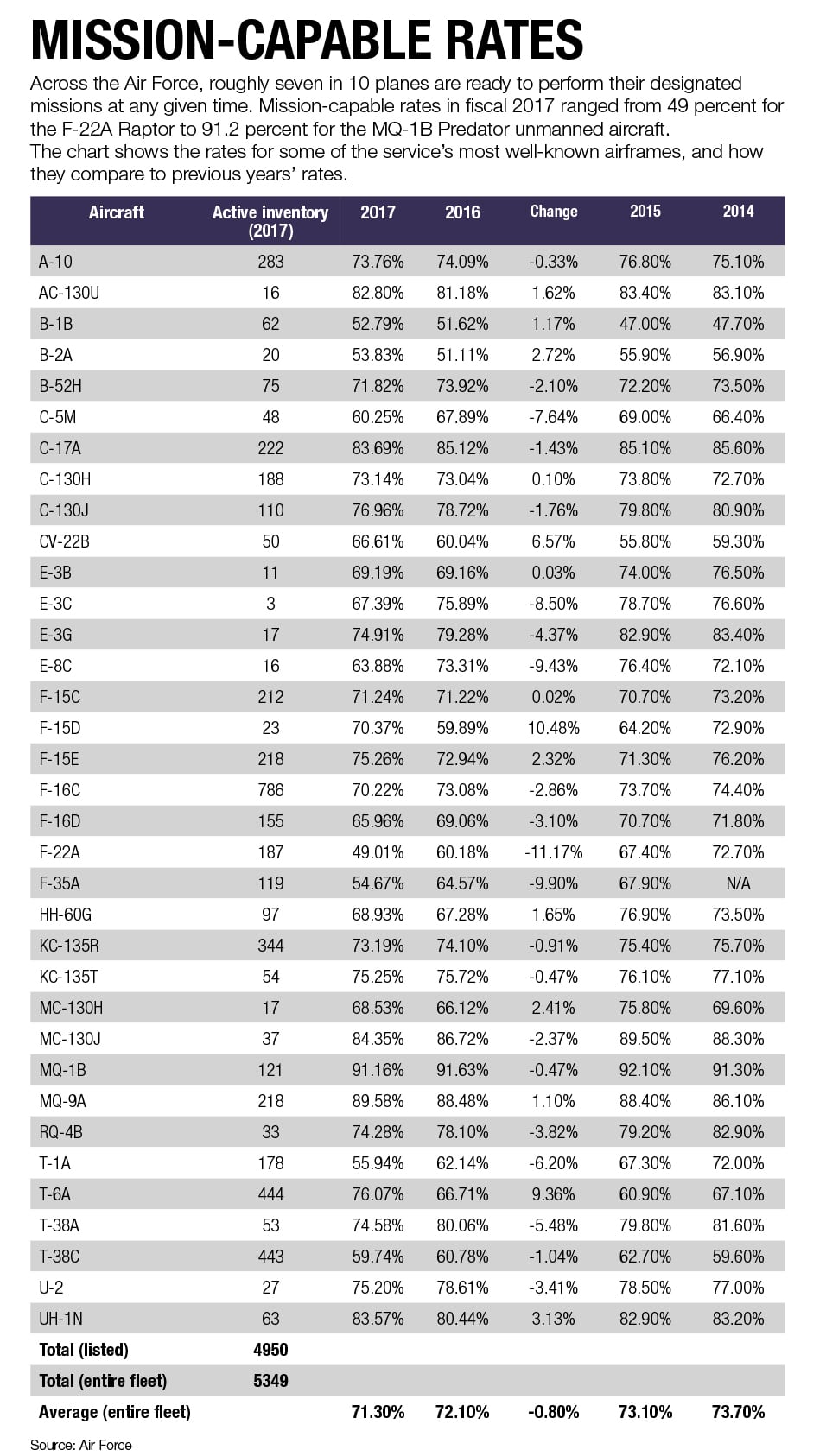

According to data provided by the Air Force, about 71.3 percent of the Air Force’s aircraft were flyable, or mission-capable, at any given time in fiscal 2017. That represents a drop from the 72.1 percent mission-capable rate in fiscal 2016, and a continuation of the decline in recent years.

Former Air Force pilots and leaders say that this continued trend is a gigantic red flag, and warn it could lead to serious problems down the road.

“It scares the heck out of me,” said retired Gen. Hawk Carlisle, former head of Air Combat Command. “It really does.”

“We are seeing an Air Force that is back on its heels,” said John Venable, a Heritage Foundation fellow and former F-16 pilot who flew in Iraq and Afghanistan. “They’re all on the backside of the power curve.”

Look closer at some of the service’s most crucial air frames, and even more alarming trends emerge.

In fiscal 2014, almost three-quarters of the Air Force’s F-22 Raptors were mission capable. But since then, the Raptor’s rates have plunged — by more than 11 percentage points in the last year — and now less than half are mission-capable.

The F-35, the Air Force’s most advanced fighter, also saw a nearly 10 percentage-point drop.

It’s not just fighters. Mobility aircraft such as the C-5 and C-17, surveillance aircraft such as the E-3 AWACS and E-8 JSTARS, and the B-52 Stratofortress are some of the other critical aircraft that saw mission-capable rates decline.

The B-1B Lancer and B-2A Spirit bombers experienced some improvement over 2016 — but even they are still mired in mission-capable rates of about 52 percent or 53 percent.

The mission-capable statistics would be even worse without the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper, which are consistently around 90 percent and are by far the highest in the Air Force.

When those two RPAs are removed — and the Predator is to be retired from service March 9 — the overall mission-capable rate drops to 70 percent.

How we got here

Multiple factors over the past few years have led the Air Force to this crisis point. The Air Force has been flying its aircraft exceptionally hard for years, fighting wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, as well as providing deterrence against North Korea, Russia, and China.

For example, the F-22 is getting flown more downrange these days — in places like Afghanistan and Syria — than the Air Force originally expected, Carlisle said. That means more breakage, and thus the need for more spare parts.

Heavy deployment rates, Carlisle said, also lead to strain on the air frames, requiring more maintenance.

But finding maintainers to fix those airplanes is not so easy. The Air Force cut its maintainer ranks during the severe drawdown of 2014 — a serious mistake, Carlisle said, that is coming back to haunt the service.

The Air Force has made some progress, and has now brought the maintainer shortfall from its high of 4,000 down to about 200. But many of those new maintainers are less-experienced, with a skill level of 3, Venable said.

Those 3-levels can do some work, and more-experienced 5-levels can do more advanced repairs, he said. But they need a seasoned 7-level maintainer to sign off on much of that work — and the Air Force remains alarmingly short of 5- and 7-levels, Venable said.

Gen. Carlton Everhart, head of Air Mobility Command, also pointed to the pace of operations and maintenance

“I think the reason why they’re declining is, we are really flying aircraft hard,” Everhart said Feb. 21. “It winds up being a balance. If you fly aircraft hard and don’t give them much of the maintenance time they need, then they will have a tendency to bring those rates down. If you balance those rates and maintenance capability to operations, that gives you a more definitive mission-capability rate.”

Considering how crucial logistics are to keeping the military functioning, Everhart said he’s “absolutely” concerned about any signs of declining readiness.

“It’s kinetics that win the battles, but it’s logistics that win the war,” Everhart said. “Anything that’s taking those airplanes away, where you can’t see the power of the United States Air Force, that does concern me.”

AMC stood down dozens of its C-5s and launched a fleet-wide maintenance assessment after the nose landing gear malfunctioned on two planes at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware last summer.

Spokesman Col. Chris Karns said AMC is looking to partner with the Air Force Reserve to swap out its aircraft and extend their service life and reliability.

Deployers first

The Air Force makes sure its deployed squadrons have the most senior, experienced maintainers to guarantee that planes flying combat or other forward missions are in the best shape.

But Carlisle said that means bases back at home, which are already short-staffed on maintainers, don’t have as many experienced maintainers to keep those planes up and running.

When it comes to new aircraft, Carlisle said, it takes a while to spin up newer maintainers on how to fix them — especially something as advanced and complicated as the F-35.

And stealth aircraft such as the F-22 and F-35 need more work to maintain their stealth coatings, which brings down their availability, he said.

“It’s more than just corrosion control,” Carlisle said. “There’s a lot of science to the entire stealth process.”

The age of the Air Force’s fleet is catching up with the service. With the Air Force deciding to keep older planes such as the A-10 and F-16 on longer, and a lack of recapitalization for some crucial air frames, the service’s iron is getting tired, Carlisle said. The average age of an airplane, forcewide, increased from 27 years in 2016 to 27.6 in 2017.

This leads to complications.

The C-5M, for example, is more than three decades old, Carlisle said, and unexpected parts are breaking.

When you’re dealing with planes that old, sometimes the Air Force finds it has run out of spare parts, Carlisle said, and the companies that used to make those specialized parts have stopped making them or are out of business.

“We’ve gotten pretty good about putting money into parts, but because of the age of the fleet, we still have challenges with diminishing manufacturing sources,” Carlisle said.

Pat Kumashiro, a retired colonel and former head of the maintenance division for the Air Force’s Logistics, Engineering and Force Protection Directorate, said that for many old aircraft — such as the nearly 56-year-old B-52 — the Air Force often has to pull spare parts out of the Boneyard, an aircraft graveyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona.

That’s not an ideal solution, he said, so the Air Force is looking at other options, such as 3-D printing.

But that has its own drawbacks — particularly since 3-D printed parts in most cases aren’t as strong as traditionally fabricated parts, and can’t be used for crucial systems where they might break.

RELATED

‘Pilots who don’t fly’

But no matter the cause, declining mission-capable rates present a problem the Air Force must fix. And if it doesn’t, experts agreed, it could drive more pilots out and exacerbate an already alarming pilot shortage.

The Air Force needs about 20,000 pilots across the total force, but despite taking many steps to retain them, the service remains about 2,000 pilots short.

A major driver is that pilots are being recruited for lucrative flying jobs in the commercial airline industry.

As Chief of Staff Gen. Dave Goldfein has often warned, “Pilots who don’t fly … will not stay with us.”

But if there simply aren’t enough operational planes, pilots don’t get nearly as many flying hours. Venable said pilots should get about 20 to 25 hours of flight time per month.

In a March 1 discussion with Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson at Heritage, Venable said pilots used to require three weekly flights, or 15 to 20 hours of flight time a month, just to stay sharp with their current skills. Learning new skills required four weekly flights, he said.

Wilson said that overall, pilots now get an average of 17.6 flight hours per month. Fighter pilots get about 16.4, she said, and mobility pilots fly about 17.3 hours per month on average. Bomber pilots, who fly longer sorties, fly about 19.7 hours per month on average, she said.

The problem, Venable said, is that those averages don’t tell the entire story.

Deployed pilots fly much more frequently and fly longer sorties than those stateside. That means stateside pilots are, in most cases, flying less than the monthly average, and their skills atrophy.

The Air Force needs to do much better when it comes to flying hours, Venable said. Not only is it demoralizing to have some of the best pilots in the world stuck on the ground, they start to lose their competencies if they don’t fly.

This runs the risk of sending the Air Force into a “death spiral,” he warned.

“Flying hours is the big one. That’s where the rubber meets the road,” Venable said. “They fly four times a month, or five times a month, and that’s what you’re going to give them? Why would anybody want to stay in that force?”

The bottom line

If one of the many hot spots around the world erupts — such as North Korea — the Air Force could find itself in a situation where the crucial planes it needs to respond are out of commission.

“The risk [of such a scenario] continues to go up,” Carlisle said.

To fix it, “we need to buy more airplanes, we need to increase our end strength, and we need to modernize and recapitalize our fleet,” he said.

Otherwise, this problem could have serious repercussions on the Air Force’s combat capabilities.

“It’ll be something on the order of the spiral down of the United States Air Force into something that may not be as combat-effective as we need it to be when the day comes,” Venable said.

Reporter Charlsy Panzino contributed to this report.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.