The next generation of fighter pilots might be found behind a joystick ― or, at least, that’s what the Air Force is gambling on.

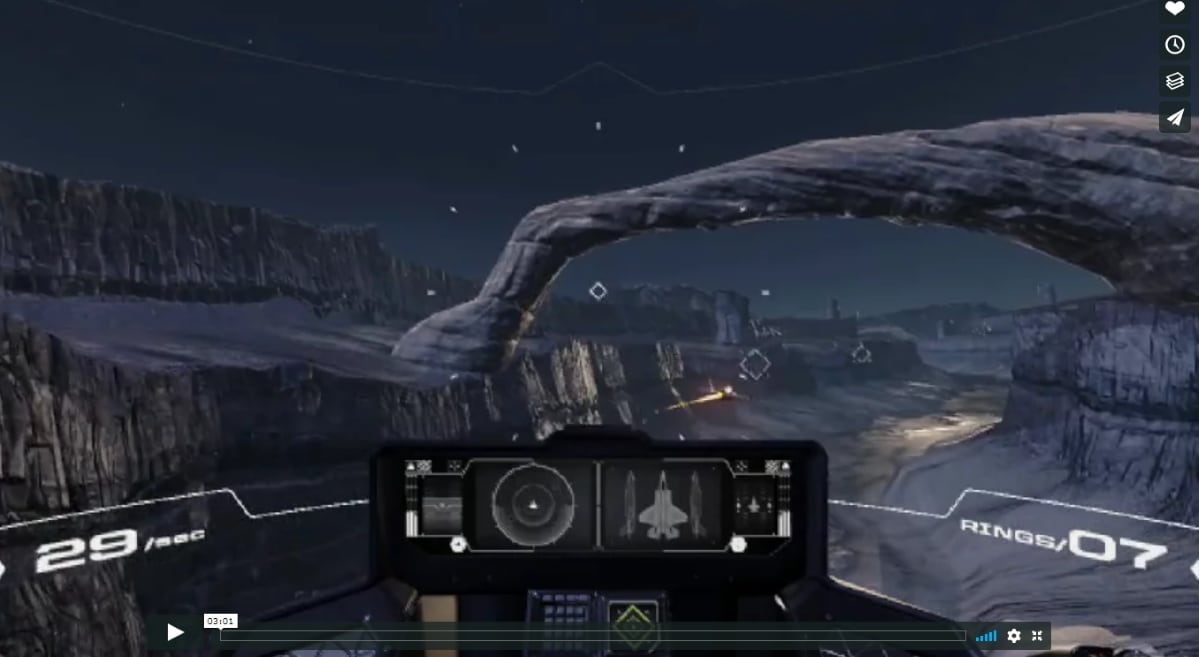

The Air Force is working on an online video game that it hopes will allow it to find and recruit talented young people.

In a breakfast with reporters in Washington Thursday, Lt. Gen. Steven Kwast, head of Air Education and Training Command, said he hopes the first iteration of this game will be ready this summer.

And when asked whether the game will be a flight simulation or also include other abstract, puzzle-solving types of challenges, Kwast said, “It’s all.”

The Air Force won’t see the names of players, Kwast said. But if a young person demonstrates the right skills and characteristics to be a pilot or other kind of airman, the service could send a message nudging that person to talk to his or her parents about a career in the Air Force.

“When someone says, ‘I want to be a pilot in the Air Force,’ and they’re out in high school or college, I can have them play a game online, and that game gives me insight into their skill, their knowledge, their attributes and their characteristics,” Kwast said. “I don’t need to know their name, but I know that IP address so-and-so has really got unique skills to be a helicopter pilot, or to be an F-35 pilot, or whatever it might be. And then I can start recruiting that person and marrying up their propensity, their passion and their talents with my requirements in the Air Force.”

If the scenario sounds reminiscent of the movies “Ender’s Game” or “The Last Starfighter” ― in which youths who score highly on flight simulator video games are recruited to fly fighter spaceships and save the universe ― the comparison has also occurred to Kwast.

The AETC commander called the creators of “Ender’s Game” “really, wicked smart” for their ability to predict innovative uses for technology in the future and its implications. The original novel was written by Orson Scott Card, and the movie was written and directed by Gavin Hood.

“Throughout history, storytellers and futurists can see deep into human nature and technology far beyond the average populace,” Kwast said. “They always have. This is why movies are so interesting to us.”

Kwast said the Air Force has worked with a team of sociologists, psychologists and cultural anthropologists to create its online game.

Data from a program called Pilot Training Next ― which began in February and uses advanced biometrics, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality systems to try to find new ways to train Air Force pilots ― is also “pouring in” and helping craft the game, he said.

And the video game can show the Air Force more than just how good a player’s hand-eye coordination is, Kwast said. It can also measure a potential recruit’s capacity for critical, collaborative and creative thinking, he said ― as well as other aspects of the player’s character.

“I can tell if you’re empathetic,” Kwast said. “I can tell if you cheat. I can tell if you cut corners. I can tell if you’re morally courageous under pressure, or whether you save your own skin. Are you selfless? I can tell all kinds of propensities, attributes, characteristics, knowledge and skill. That’s where we’re going, because I want someone who has high integrity, who has the right intellect, who has the right passion.”

RELATED

And the Air Force could filter different players’ results to “dial in” specific attributes that go with a particular job, such as a maintainer, and then find which players best matched those attributes and try to recruit them, Kwast said.

But, he stressed, while the Air Force might send messages to players, it would not know who is playing the game, or directly recruit minors beyond suggesting they talk to their parents about a career in the Air Force.

“If there’s a 15-year-old kid out there that is just on fire, intellectually and cognitively, to be a fighter pilot, let’s say, I have no right to know who they are,” Kwast said. “Their privacy, their independence, their civil liberties. The policies are that we can look at the data, but we will not look at you.

“But if I find this 15-year-old kid that is just brilliant,” Kwast continued, “I’ll probably send a message to that IP address saying, ’Go tell your mom and dad that you are special, and I will offer you a $100,000 signing bonus, and I’ll send you to Harvard for four years for free if you’re willing to tell your parents to come in to the recruiting station, or come out to the airport when we have the recruiters there to meet with somebody who could put a face to the name.’ But we go through the parents, of course.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.