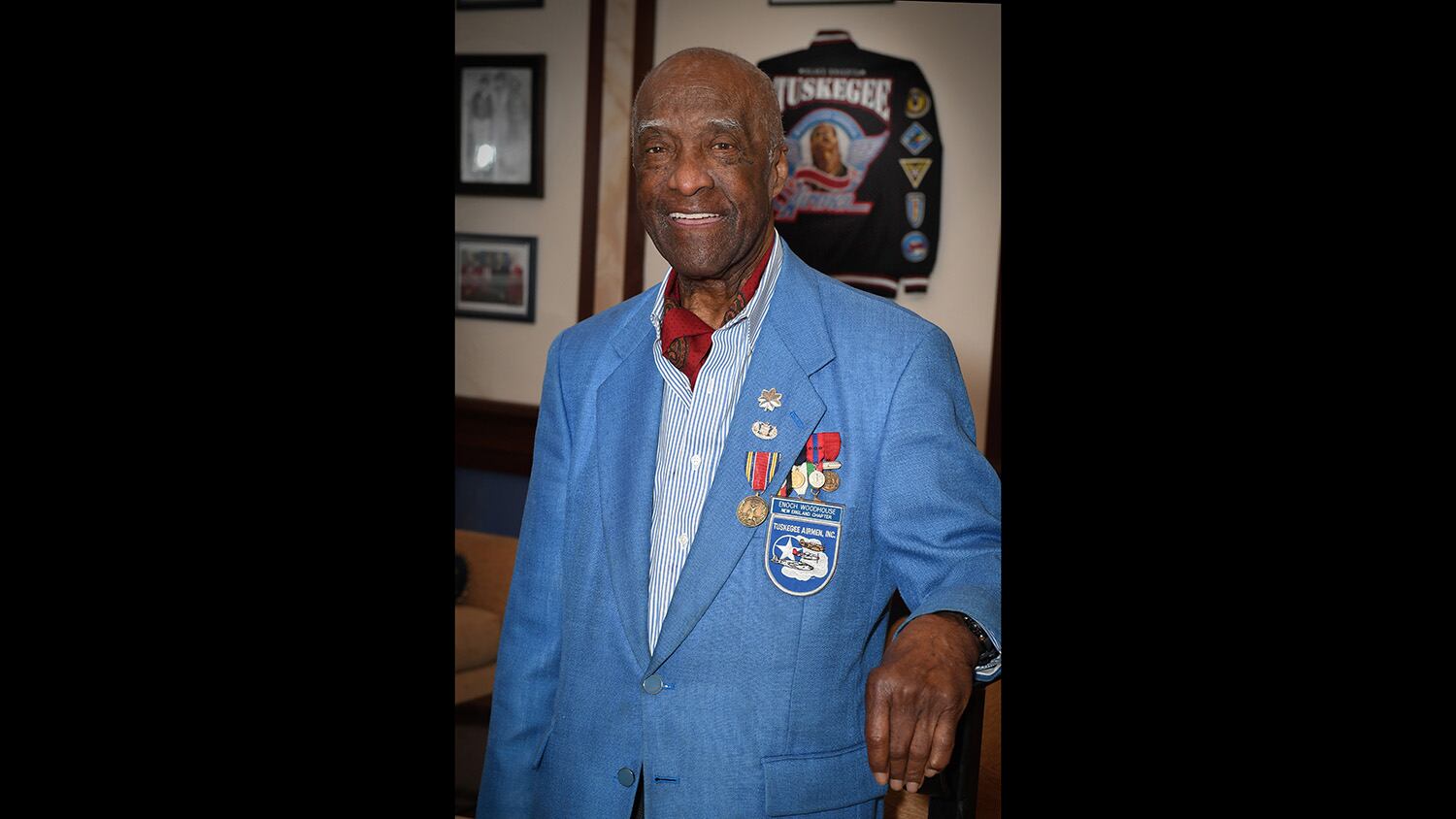

FORT BRAGG, N.C. — Moments before retired Air Force Lt. Col. Enoch Woodhouse Jr. addressed a group at Fort Bragg, he described an instance when he was kicked off a train in the 1940s because of the color of his skin.

"That was one of the most embarrassing times in my life," said Woodhouse, who is 92.

Woodhouse, a Tuskegee Airman, spoke to soldiers and guests at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School for Black History Month. The Tuskegee Airmen were the nation’s first black military pilots. They received their flight training from the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama when the U.S. entered World War II.

"Black history — it's not black history to me. It is American history, our history," Woodhouse told the crowd.

RELATED

In an interview with The Fayetteville Observer prior to Monday’s event, Woodhouse recalled his mother’s words following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

"She said 'Sons, our country is at war. I want you boys to serve our country,'" Woodhouse said.

His brother would become one of the first black Marines at Montford Point, North Carolina.

After graduating from Boston English High School in 1944, Woodhouse enlisted in the Army with about 20 of his classmates.

The train incident soon followed when he received his first assignment to go to Texas.

Woodhouse said he traveled from Boston to Chicago and from Chicago to St. Louis with no problem.

It was in St. Louis when the conductor tapped him on the shoulder and told him to get off the train — while he was in uniform.

A black porter asked him where he was from and if he'd ever been to the South before. Woodhouse is a native of Boston, where he currently lives.

"He said, 'We don't ride that train,' and said I'd have to wait for the next train," Woodhouse said.

That next train was a cattle car that arrived about 10 hours later.

Woodhouse said he was considered absent without leave for not reporting to duty on time, and his white first sergeant didn't allow him to explain.

"That was my first day. This is something I'll never forget . . . I never told my mom . . . my technique to survive was to suck it up and move on," Woodhouse said.

Woodhouse said while in the Army Air Corps, he was assigned to Squadron F, which had a housekeeping mission to shovel snow, refuel aircraft or peel potatoes.

He said leaders were white, and he never saw a black noncommissioned officer until about a year into his Army service.

By the age of 19, Woodhouse attended Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. His next assignment was with the 332nd Fighter Group of the Army Air Corps.

He was discharged from the Army in 1949 and joined the U.S. Air Force Reserves. He was assigned to the Air Force Judge Advocate General office in 1956 after earning his law degree. He retired from the Reserves as a lieutenant colonel in 1972.

Addressing Monday’s crowd, Woodhouse spent little time talking about himself. Instead, he focused on two others: Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a 1938 West Point graduate and commander of the Tuskegee Airmen, and Navy Capt. Thomas J. Hudner Jr., who was white.

Woodhouse titled his speech “the arc of justice,” and used what happened to Davis and Hudner as a way to illustrate its theme.

Woodhouse said Davis had the "burden of suffering" four years at West Point, which would later name its barracks after him.

"As Americans — black, white, Asian, no matter what — somehow, somewhere we get our act together and we do the right thing," Woodhouse said. "I'm 92. It takes a long time to wait, but if you have faith, which I have, that's the only thing that got me through this thing."

He also spoke about Hudner.

Hudner's wingman was a fellow Annapolis classmate, Jesse Brown, who was black, Woodhouse said. Brown was involved in a crash in Korea, and Hudner attempted to rescue him. Brown died in the mountains with frostbite, and Hudner's plane also crashed.

Woodhouse said Hudner was chewed out once he returned to his naval carrier and threatened with a court-martial for destruction of government property.

Hudner's mother intervened and spoke to a senator, who spoke to President Harry Truman, who told the chief of naval operations to write orders for a Medal of Honor for Hudner, Woodhouse said.

Years later, Hudner would ensure that Brown's daughter and granddaughter had money to go to school and asked that the Navy christen a vessel in Brown's honor instead of his own, Woodhouse said.

"We all have situations that force us to, that compel us to use our God given talent and what our innate abilities call upon us to do," he said.

As for Woodhouse, he practiced law for more than 50 years and served as a diplomatic courier for the U.S. State Department in Europe, Africa and South America after his military service.

In 2007, he and fellow Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by then-President George W. Bush.

Brig. Gen. Harrison Gilliam, deputy commanding general of the special warfare school, said Woodhouse served his country with distinction and honor.

“When his fellow countrymen didn’t see fit to treat Woody as they would others, he held his head up high, he made no excuses, and he did what his job called to do,” Gilliam said.