The Air Force’s aircraft readiness continued its multi-year slide in fiscal 2018, as the overall mission-capable rate for the aging fleet dropped below 70 percent — its lowest point in at least six years.

Of the 5,413 or so aircraft in the fleet, the percentage that are able to fly at any given time has decreased steadily each year since at least fiscal 2012, when 77.9 percent of aircraft were deemed flyable. By fiscal 2017, that metric had plunged to 71.3 percent, and it dipped further to 69.97 percent in 2018, according to statistics obtained by Air Force Times via the Freedom of Information Act.

That is an overall decrease of nearly 8 percentage points since 2012.

Moreover, the decline has continued despite the Air Force’s growing concerns about readiness and its best efforts to reverse the trend. So far, however, it appears to have little to show for it.

“The Air Force has got a big hole it’s got to dig itself out of, and they’re taking their time doing it,” said John Venable, a Heritage Foundation fellow and former F-16 pilot who flew in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A STEADY DECLINE

After years of slow but steady declines, fewer than seven in 10 planes are ready to perform their designated missions at any given time.

| Fiscal year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall MC rate | 77.90% | 77.80% | 73.70% | 73.10% | 72.10% | 71.30% | 69.97% |

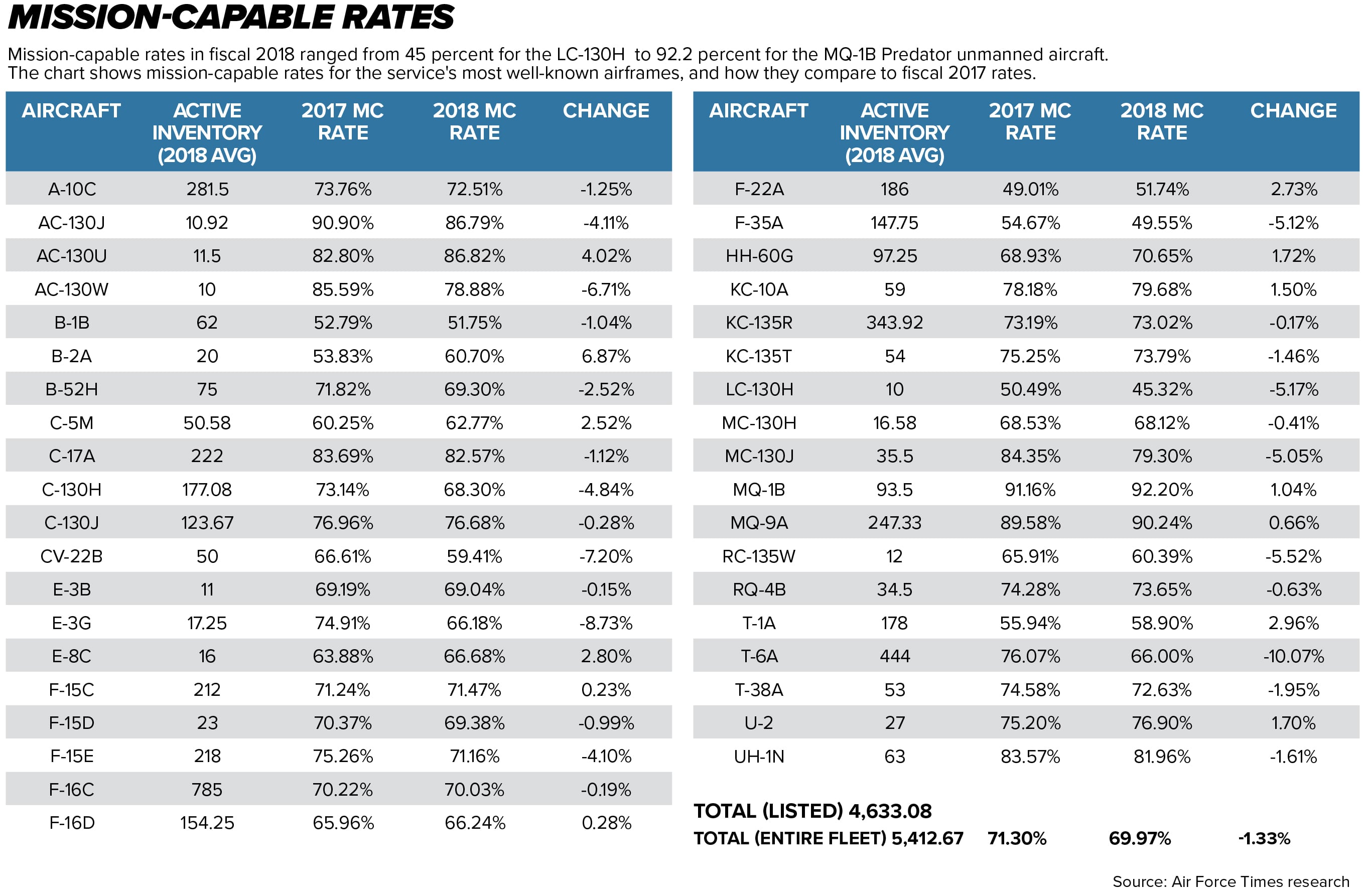

In all, 39 of the Air Force’s 87 air frames saw declines in readiness, some significantly. And they include some of the service’s most vital aircraft. Among the most alarming declines from fiscal 2017 to FY 2018:

♦ The F-35A Lightning II fighter, down 5 percentage points. Fewer than half of the Air Force’s 148 F-35s were deemed mission-capable in 2018;

♦ The F-15E Strike Eagle, down 4 percentage points;

♦ The CV-22 Osprey, down 7 percentage points;

♦ The E-3G Sentry airborne warning and control system, or AWACS, down nearly 9 percentage points;

♦ The C-130H Hercules mobility aircraft, down nearly 5 percentage points;

♦ The T-6A Texan II training aircraft, which was grounded repeatedly in 2018 for problems with hypoxia and other physiological episodes. The T-6’s readiness rates fell 10 percentage points as a result.

In a July 17 interview, Col. Bill Maxwell, chief of the Air Force’s maintenance division, said the overall decline is concerning.

“Any degradation in readiness that we have, our ability to be able to perform our mission, is absolutely a concern to a tremendous amount of people,” Maxwell said. “Not least of which are the maintainers and the operators out there in the operational wings, but also all the way up to the Air Staff here as well.”

In a follow-up statement July 18, Maxwell said the overall rate is a “snapshot in time,” and that a 5 percent fluctuation is considered a standard variance. He also said aircraft can be coded as non-mission capable for several reasons, including routine scheduled maintenance and modernization.

“I agree that any degradation in readiness is something the USAF will continue to work to understand and mitigate within the resources we have,” Maxwell said. “However, I don’t agree that the numbers provided here provide a valid representation of the Air Force in their simple form.”

Air Force spokeswoman Ann Stefanek also said in a July 21 email that “Mission capable rates do not equate to Air Force readiness rates. They are just one component assessed at the unit level to help determine how ready a squadron is to meet the threat.”

The Air Force attributes the decline to several factors, according to a July 15 statement from spokesman Robert Leese. The primary culprit is the advancing age of the fleet, which hit 28 years on average across the total force. Notably, the average age of a fighter or attack aircraft was 27 years in 2018, as opposed to 1991 when they were 10 years old on average.

“The longer we extend the service life of our legacy aircraft, the more investment, inspection man-hours, preventive maintenance and manpower they will require,” Leese said in the email.

Maxwell noted that as the Air Force modernizes and makes improvements to its aircraft, mission-capable rates can take a hit.

Still another factor is that the manufacturing sources the Air Force has traditionally relied on for unique spare parts and materials have dried up, so the service is increasingly forced to scavenge parts from old airplanes retired to the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group – also known as the Boneyard.

When spare parts can’t be found there, the Air Force turns to contractors to specially create them, he said. But that carries its own set of problems, because contracting out for those rare parts can be costly and take a while to produce.

“It leads us to a place where those lack of parts are problematic,” Maxwell said.

Retired Gen. Hawk Carlisle, who formerly commanded Air Combat Command and is now head of the National Defense Industrial Association, acknowledged the Air Force hasn’t yet turned the corner. But he cautioned that mission-capable rates can be a lagging indicator. While the Air Force has put more money into the budget for spare parts and improved maintenance manpower, he said, it takes time for those changes to translate into readiness improvements.

Preparing for combat

The troublesome mission-capable rates also complicate the Air Force’s effort to meet former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis’ directive to get three of its key fighter jets – the F-16, F-22 and F-35 – up to 80 percent readiness by the end of September.

Because the fiscal 2018 numbers ended just two weeks after Mattis issued his order last year, they do not provide a true indicator of how well the Air Force is doing in meeting those goals. But they show the starting point for each air frame – and how hard the job is proving to be.

The F-16’s C and D models each saw little change between 2017 and 2018, and finished 2018 with overall mission-capable rates of about 70 percent and 66 percent, respectively. The Air Force said that the 80 percent goal referred to only combat-coded aircraft, not overall aircraft, and that it expects to hit that goal for combat-coded planes by the end of the year.

But F-22s, which did improve by about 2.7 percentage points to 51.7 percent, and F-35s, which dropped 5.1 points to 49.6 percent, will not meet that goal, the Air Force said.

Mark Esper, now the newly-confirmed secretary of Defense, said in written policy answers to the Senate Armed Services Committee considering his nomination July 16 that increasing parts supplies and adding maintenance shifts has improved the F-16’s mission-capable rates.

But the F-22 fleet is hampered by a lack of maintenance capacity, Esper said, which is further complicated by its low-observable coating. Hurricane Michael’s devastation of Tyndall Air Force Base made things even worse, he said.

For the F-35, Esper said the main obstacle is a significant shortage of canopies. The military is looking for additional sources to replace the F-35’s unserviceable canopies.

While the Air Force is trying to iron out lingering issues with the F-35, Carlisle said, it is also increasingly using and deploying the advanced fighter, and that, of course, affects its readiness. As the F-35 is used more in combat and real-world missions, he said, expect more wear and tear on it.

Meanwhile, the Air Force is “using the heck out of” the F-15E, Carlisle said, which contributed to its readiness decline to 71.2 percent last year.

“We’re putting those things just about all over the world,” Carlisle said.

The effect on pilots

As the Air Force has struggled with aircraft readiness, it has focused its attention on ensuring aircraft at deployed locations – especially those engaged in combat operations or that could be called upon to fight – are ready to fly.

But prioritizing deployed aircraft can mean the readiness of stateside planes suffers. If there are fewer planes for pilots to train on, that translates to decreased readiness for pilots.

“Clearly, when you have a decrease in [mission-capable rates], there are less aircraft available for training your operators and pilots,” said Pat Kumashiro, a retired colonel who led the maintenance division for the Air Force’s logistics, engineering and force protection directorate. He is now director of the Air Force market at LMI, a nonprofit consulting firm.

The ongoing pace of deployments, including regular missions in Afghanistan and against the Islamic State, exacerbates the situation and makes it harder to train, he said.

Deployments also put more strain on aircraft, Venable said. They’re flown harder in battle and on other missions, which requires more maintenance.

The bottom line, Kumashiro said, is that the Air Force has “tired iron.” As aircraft such as the F-15 and F-16 hit three decades or more in action and require service life extensions, the work can involve replacing or strengthening structural parts such as bulkheads, wings and canopies, which requires time and effort and takes aircraft off the line.

The long-term solution, Kumashiro said, is for the Air Force to focus on adding newer aircraft such as the F-35, KC-46 and B-21, allowing it to retire its older planes that require more maintenance.

Hard choices

But Venable sees it another way. The Air Force has put the lion’s share of its new funding in research and development, he said, “banking on the future” to create new aircraft, as opposed to investing in operations and maintenance. As a result of that funding choice, he said, money for spare parts has been lacking – and mission-capable rates have suffered as a result.

In addition to a lack of spare parts and funding, Venable sees room for the Air Force to improve in how it organizes its maintenance.

The service’s shift to a two-level maintenance program that relied more on depots to consolidate and handle certain maintenance jobs for several bases has contributed to the problem, he said. While it has saved the Air Force money and created efficiencies, Venable said, it’s also created bottlenecks where planes and components wait in line, and units wait for them to get fixed and be sent back. Depots also operate under union rules, he said, which limit how long the maintainers can work.

If the Air Force brought more maintenance work back on-site to the flightlines, Venable said, it would have more flexibility to have airmen work longer hours when necessary. When former Tactical Air Command head Gen. Bill Creech tried this in the 1980s, Venable said, competition between Air Force units working on their aircraft led to higher mission-capable rates.

“If [mission-capable] rates are going to improve, and the Air Force is not going to put any money towards it, then the only other way to do it is organizationally,” Venable said. “You’re going to lose quote-unquote ‘efficiencies’ in this process, but your [mission-capable] rates are going to explode.”

Maxwell isn’t so sure. Adding more repair capacity to individual installations could, theoretically, bring up mission-capable rates. But there’s a trade-off, he said. It would likely be much more expensive.

“We don’t … have infinite money, and we just don’t have the ability to have full repair for every component at every location,” Maxwell said. “No matter how wonderful that sounds, that would be extremely expensive. We need to figure out the ways to do that efficiently, but still be effective, which comes down to really good communication [between maintenance shops] and the ability to move parts when necessary.”

The experience factor

For years, the Air Force struggled with severe shortfalls in its maintenance career fields. At one point, the Air Force was down about 4,000 maintainers – a problem that was exacerbated by the service’s steep downsizing in 2014.

But while that shortfall is now closed, Maxwell said, many bases have more 3-level apprentice maintainers than they need, and not enough 5-level journeyman or 7-level craftsman maintainers. It takes years for those young maintainers to get the kind of seasoning and experience with specific air frames they need.

And this complicates matters, he said.

“We had less experience on the flightline than we would have liked,” Maxwell said. “And while you’re struggling with that, you’re … first trying to maintain and sustain those airplanes. But you’re also trying to train that force. It’s a lot of effort to do both those things.”

Leese, the Air Force spokesman, said the Air Force still must grow its maintenance force to meet the requirements of the new F-35, KC-46 and B-21 air frames.

Airmen and contractors across the Air Force are doing impressive work to improve aircraft readiness rates, Maxwell said, but the service needs to do a better job connecting them so they can share their needs, observations and the lessons they’ve learned.

This is especially important, for example, when a problem such as the hypoxia issue that plagued T-6s last year crops up. Better communication between maintainers on the flightline could help catch those problems earlier and zero in on possible causes and solutions for them.

“How, collectively, are we communicating the way that we are doing this work together to make sure that we’re learning lessons from each other, and we’re not having to all learn the hard lessons the hard way?” Maxwell said.

Leese said the Air Force is also looking at new technologies to improve readiness and decrease maintenance downtime. This includes additive manufacturing, such as 3-D printing, as well as analytics that use vast amounts of data to create models that can predict when an aircraft’s part is likely to break, instead of waiting for it to fail.

One predictive maintenance program, known as conditions-based maintenance, is expected to cut the number of unscheduled maintenance events, Leese said. Conditions-based maintenance will allow maintainers and operators to decide when and where the maintenance should be performed, he said.

The E-3, C-5, KC-135 and B-1 are already using some form of predictive analytics, Leese said, and the C-130H and J aircraft, as well as C-17s, are expected to start using conditions-based maintenance soon.

F-16s will be the first fighters to use this program, Leese said, and a joint effort across the Defense Department is working on putting it into place for the HH-60 Pave Hawk.

The Air Force is studying and investing in several best practices from industry, including conditions-based maintenance, Esper told lawmakers at his confirmation hearing. If he is confirmed, Esper said, he will continue to push the Air Force to improve its mission-capable rates.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.