When Terrence Greene was growing up in his family’s tiny village in Guyana, there were a lot of things about his story that didn’t add up.

He didn’t look like his brothers and sisters. He didn’t know why he lived with his aunt and uncle, while the rest of his siblings lived with their father and stepmother.

But most perplexingly, he never knew the true story of the fire that took his mother’s life, when he was just six weeks old.

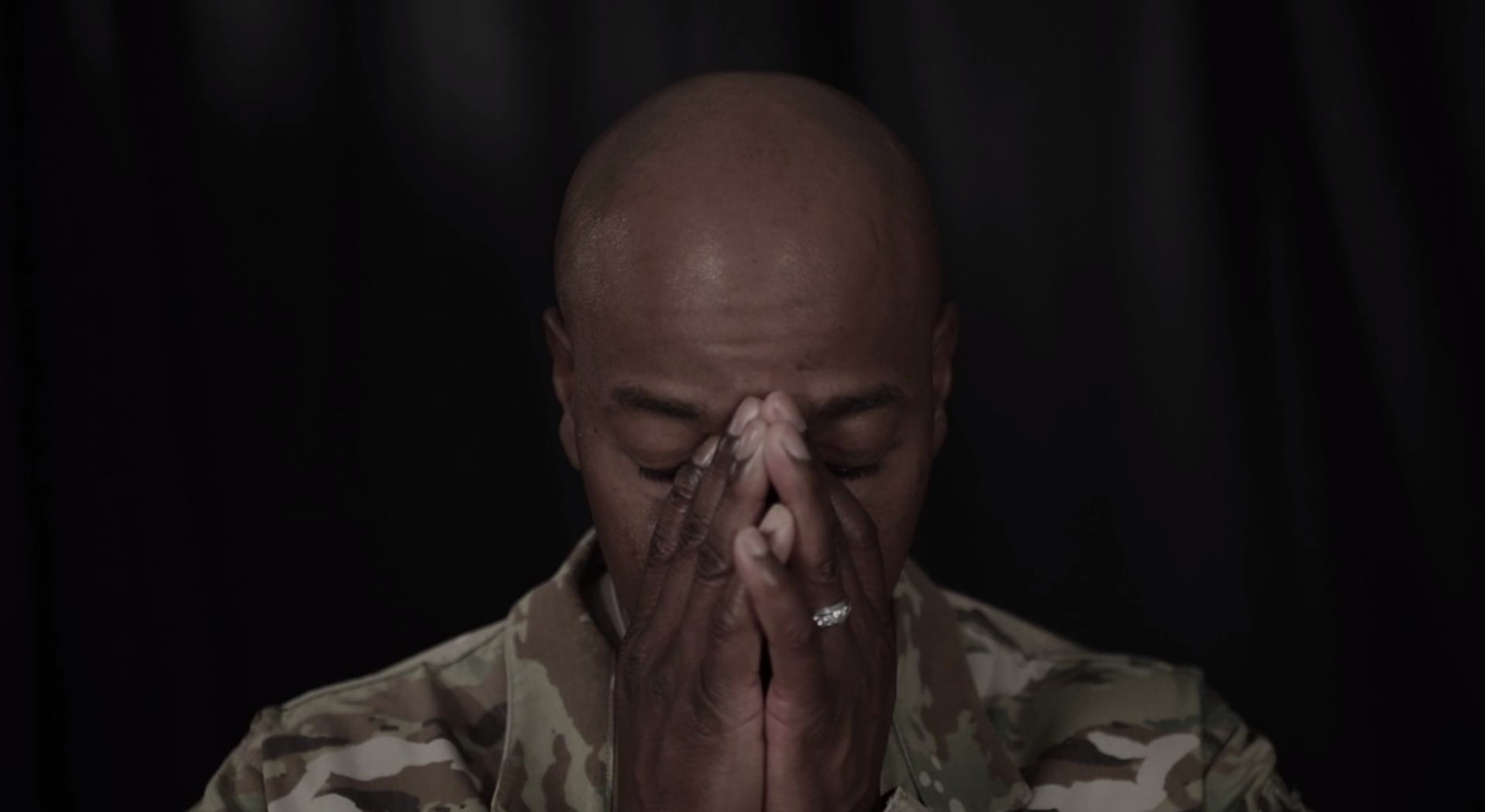

Eventually, Greene started to unravel the mystery — and tragedy — of his origins. What he learned left him deeply unsettled and searching for meaning, even as he pursued a career in the Air Force.

But now, Greene — today the command chief master sergeant of Air Mobility Command — has found peace with his family’s story and the turmoil it caused him for decades. And as much of the Air Force is struggling to improve airmen’s mental health and resiliency, he’s hoping that his example can help serve as a guide.

“It took me years to work up the courage to even share my story with my closest associates,” Greene said in a Dec. 11 interview. “Saying that people are our most valuable resource should be way more than just this bumper sticker.”

Greene was born in New Amsterdam, Guyana, in January 1964, the sixth child in his troubled family, and grew up in the coastal village of Goedverwagting. His father was abusive to his mother, Louiza, he said, and had other women on the side. When Greene was born, it was apparent that his mother had also had an affair.

“I came out not looking like the others,” Greene said. “I showed up as mixed with Indian and black, and all of my other brothers and sisters were black. So it was clearly obvious that I was not his child.”

His mother was deeply shamed after that revelation, Greene said — and the effect was devastating. One day a month and a half later, she had one of Greene’s sisters bring her a can of kerosene. With all her children still in the house, Greene said, she poured it on herself and set herself on fire.

After about two weeks in the hospital with third-degree burns, she died.

Greene’s family was traumatized. His father remarried within a few months — “which kind of tells you where he was on all this,” Greene said. His siblings went with their father and new stepmother. But, Greene said, his father had no intention of raising a boy who wasn’t his, so he was instead taken in by an aunt and uncle on his father’s side.

Greene ended up with the better living situation. His stepmother was abusive to his siblings, he said — one sister died and a brother developed epilepsy, he believes due to her abuse.

He grew up being told that the man who was married to his mother was his biological father, and assumed that the fire that killed his mother was an accident. And for years, he believed it.

“Your brain finds a good story that it could live with,” he said.

But eventually — around the time he was 9 or so — he started to realize something was off. He didn’t look like anyone else in his family. What’s more, he started to hear from other kids in the village that his mother had actually killed herself.

RELATED

One day, he sat down with his maternal grandmother to talk. For the first time, he learned the true story of the abuse his mother suffered and what happened to her. It was terrifying, he said.

Greene blamed himself. For his mother’s death, for the abuse and further trauma his siblings suffered, for everything that happened after the mere fact of his existence exposed his mother’s affair.

“Had I not been born, this would not have happened to them,” Greene said. “My mom would be alive, had I not been born. None of this trauma would have happened.”

It took Greene years to work through that trauma.

“I would always look at my life in one question: Why did my mom do that?” Greene said. “Why did my mom leave me? I went through all kinds of emotions of being angry at my mom for leaving me in the world by myself, because I don’t have any full-blooded siblings. Every challenge I had gone through, you think, I wish my mom was here.”

Years later, Greene figured out who his biological father was, but by then he was dead. He grew up feeling detached from not having parents, and always felt like he was going to be disappointed by life.

At times, when life became particularly difficult, Greene said he even struggled with his own thoughts of suicide.

“It came to that point — well, my mom did it, why not?” Greene said.

Greene himself was in particular danger of dying the same way as his mother. In 2010, the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center released a study that found children who had lost a parent to suicide were more likely to take their own lives, and were at increased risk of developing major mental health issues.

He enlisted in the Air Force in 1988, a few years after arriving in America. In his search for a new family, he poured his heart and soul into his service in the Air Force. For years, he was the go-to airman in his units, the one who could be counted on to work late and put every last bit of himself into the job.

But that came with a price. He gave more and more and more — so much so that his work habits greatly contributed to his first divorce.

“Very little of my supervisors ever looked beyond that to see how I was doing at home, how was I doing with family,” Greene said. “Our NCOs at the time, and senior NCOs, see that hard working airman — and … actually ride them like Seabiscuit. I don’t recall any of my NCO leadership saying, ‘Hey, Airman Greene, it’s OK, you don’t have to stay late, you don’t have to come in on the weekends. Why don’t you spend some time with your family?’”

Greene later remarried. As his wife came to understand the decades of personal turmoil he had endured, she urged him to get help, and in 2010 — during his first year as command chief at Joint Base Charleston in South Carolina — he worked up the courage to see a Military and Family Life Counselor. Under the MFLC program, the military brings in counselors or psychiatrists for troops to meet with, almost anywhere they like and without any documentation, up to six times. That way, someone can talk without fear of being stigmatized for pursuing mental health treatment.

It was the first time he had ever talked to any mental health professional about everything he had gone through. By talking to that counselor a couple of times, Greene started to realize that his mother’s decision was her own, and he didn’t cause it in any way. Finally, Greene started to let go of the guilt and pain he had carried for decades.

A few years later, Greene realized that sharing his story could help other airmen, who themselves may still be carrying the pain from their own lives before they joined the military. Even though it’s tough, he said, talking to others is probably the most therapeutic and freeing thing he could do for himself.

“Airmen come into the military, and we come in with baggage,” Greene said. “We come in with a lot of life experiences and things that have happened.”

He now shares his story and perspectives with airmen at gatherings both big and small — and he hears from them how much they needed to hear it. Seeing him stand up in front of a crowd and be vulnerable helps airmen who themselves have gone through trying times, but never felt comfortable sharing it before, he said.

And it’s given him a fresh perspective on how to make the Air Force a better place for airmen — at a time when the entire service is sounding the alarm on resilience and mental health.

In August, the Air Force said that it was on track to lose 150 to 160 airmen to suicide in 2019. Chief of Staff Gen. Dave Goldfein ordered a one-day stand down for units to talk about resiliency and suicide prevention.

In the Air Force, NCOs used to be pretty good at getting to know their airmen as people, Greene said, but that’s been lost.

“We used to have sergeant’s time, where we talked about life,” Greene said. “We talked about marriage and divorce and paying child support. A lot of the things that seem to be triggers right now for suicide, we talked through those things — sometimes in a joking manner, but we shared.”

But over the years, he said, the Air Force has lost that art. Instead, sergeants mostly concentrate on the mission, like getting ready for the next deployment or safety briefings when they talk to their airmen, but not talking about life.

“We need to get back to some of that,” Greene said.

Those kind of talks might have helped Greene early on, he said — having his NCO learn about Terrence, the man who came from a rough childhood in Guyana, not just Airman Greene, “the super performer, the smart airman, the airman that’s sharp, the airman that polishes his boots and has always got a creased uniform.”

Greene has talked with AMC Commander Gen. Maryanne Miller a lot about how to create a culture of caring and connectedness, and it all happens at the squadron and flight levels, he said. In fact, either Miller or Greene — or both — make a point to visit all squadron commander courses at AMC and talk about how they own the culture of their squadron.

“We got to care about the people first,” Greene said. “What we’re pushing hard on is, how are you caring for your airmen? How are you knowing your airmen? We’ve got an incredible process that trains the hell out of airmen for them to turn wrenches. But we don’t have a good process for helping them to be better men and women, for understanding life experiences.”

Caring about airmen and their personal lives isn’t just a nice thing to do, he said. It’s vital for creating an Air Force that functions as well as it possibly can.

“When things are not OK at home, [airmen] can’t be fully focused on the mission,” Greene said.

It’s especially important now that more airmen are coming in who grew up in families with divorce, or didn’t have a strong family unit growing up, Greene said.

Leaders talking about their own struggles and pursuit of mental health treatment can help encourage airmen — who might otherwise be afraid of the possible harm to their careers — to seek help themselves, Greene said. There might be some things an airman can’t do temporarily while they’re getting help, he said, such as deploying overseas where they wouldn’t be able to continue their treatment. But airmen need to think of their own health first, and career matters can come after they’ve healed.

“This is for you. This is for your family,” Greene said. “Just like if you went to a regular medical doctor for a broken arm, there’s going to be things you can’t do because you’re injured. And then after you’re healed, you can do all those things.”

But at heart, it’s up to leaders at all levels to take the first step with their airmen, he said.

“Gen. Miller always says, we’re all broken in some way,” Greene said. “It’s being honest and sharing your brokenness that makes you a more genuine leader, so that airmen feel they can also share things that they’re going through."

“This helps our airmen,” he said. "This helps our environment.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.