SCRANTON, Pa. — For more than seven decades, the story of Staff Sgt. Joseph Eugene Prokop’s life ended the same way: The Scranton airman died when Germans shot down his B-17 bomber near Frankfurt in the waning months of World War II.

It’s the story the War Department told his parents and the public when Prokop’s body returned to the city for burial in 1949, and it was the only story Ann Spearmint, 91, ever heard about her brother’s death.

As the city of Hanau, Germany, prepares to honor the memory of Prokop and two other Army Air Forces members later this month, details have emerged that are rewriting that story, adding a new layer of tragedy.

What historians in Hanau discovered — and what has been disclosed to Spearmint and the rest of her family for the first time — is that Joseph Prokop, then 22, survived the downing of the bomber only to be captured by the Germans and summarily executed after a Gestapo officer learned one of his crewmates was Jewish.

As Spearmint deals with the eruption of emotions the unexpected revelation has stirred, the Covington Twp. woman can’t help but wonder what might have been.

“To think that he was alive and could have lived how many more years,” said Spearmint, Prokop’s last surviving sibling. “He was only a kid then. For them to shoot him right there, it’s unbelievable.”

On Feb. 17, Hanau will mark the 75th anniversary of the killings of Prokop and his two fellow airmen — Tech. Sgt. Charles Bernard Goldstein and Tech. Sgt. Warren George Hammond — by erecting a memorial plaque with the names of the three Americans at the site of their executions.

Simultaneously, North Scranton-based Gen. Theodore J. Wint Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 25 will conduct a remembrance service for Prokop at his gravesite in Cathedral Cemetery.

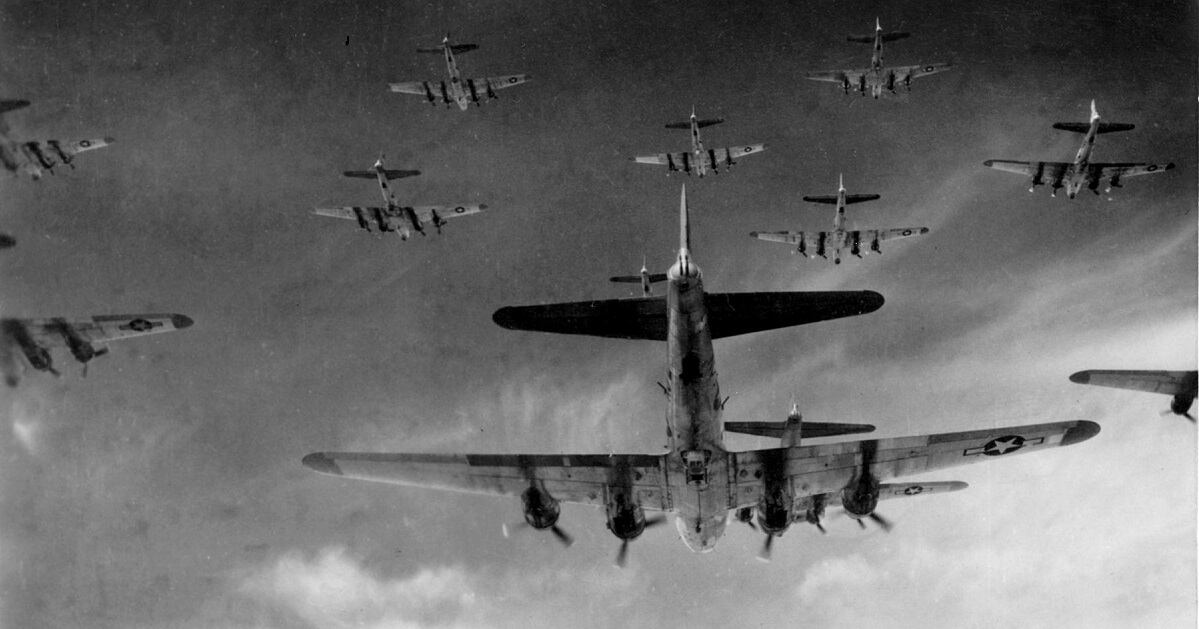

Flying out of Knettishall airfield in Suffolk, England, on Feb. 17, 1945, Prokop was the waist gunner aboard the B-17 Flying Fortress when the four-engine bomber took anti-aircraft fire while pulling away from Frankfurt airspace and went down at Hanau.

The fifth of eight children of John and Anna Prokop, the airman was born in 1922 and grew up in the St. Ann’s section of West Scranton. His father worked for the railroad, while his mother tended to the family. The parents were no strangers to tragedy as two of their five sons died before age 3.

Prokop joined in the Army in 1939, setting his sights on the Air Corps. Because her brother was only 17, Spearmint said, their parents had to sign off on his enlistment.

“My parents knew about the war in Europe and all, and they figured that one way or the other we were going to get into it,” she said. “When it happened, he was already in the service.”

RELATED

Prokop was a seasoned gunner when the B-17 took off that Saturday in February with the objective of bombing freight rail yards in Frankfurt. It was his 50th mission over enemy territory.

Although there are some discrepancies in the historical accounts, it is believed Prokop and Goldstein — along with a third airman who became separated from them and spent the last months of the war in Europe in German captivity — managed to parachute from the doomed B-17 before it crashed. The rest of the plane’s crew perished.

Prokop, Goldstein and Hammond, who apparently had been aboard a different bomber, were picked up by the police in Hanau and turned over to the Gestapo, or the Secret State Police of the Nazi regime.

While questioning the men, Gestapo director Hermann Fehrle discovered Goldstein was Jewish and became enraged, according to one account. He cursed and slapped the airman, calling him a murderer before ordering a subordinate to have all three Americans shot.

About 90 minutes later, the men were brought to a courtyard and executed one after the other.

The three German nationals subsequently convicted of war crimes for killing the unarmed prisoners all told their tribunals they knew their actions were wrong but believed they would be killed if they did not carry out the executions.

RELATED

Spearmint, who was still in high school when her parents learned in March 1945 that her brother had been declared missing in action, said her family did not receive any details.

Even when the military finally acknowledged in January 1946 that he was presume d dead, it was mostly generalities.

“I was young and I guess there’s a lot they didn’t want to tell me, but as far as I remember they said he was shot down and he was in the plane and there was one survivor,” Spearmint said.

After their deaths, Prokop and other airmen were initially buried in Hanau before their bodies were exhumed in the summer of 1945 and reinterred at the Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France. Prokop’s remains were repatriated and buried at Cathedral Cemetery four years later.

Hanau officials uncovered the long-forgotten information about the killing of the airmen while planning “Life in War,” an exhibition to commemorate 75th anniversary of the end of World War II and the city’s virtual destruction in March 1945 ahead of its liberation from Nazi control.

More research identified where two B-17s crashed in Hanau that February and the exact location where the American prisoners were slain, Mark Marrano, deputy consular chief with the U.S. State Department’s Consulate General in Frankfurt, said in an email.

When Hanau decided it would memorialize the three airmen with a plaque, organizers in the German city reached out to the consular office in Frankfurt for assistance in locating any surviving next of kin. Marrano’s office in turn started making inquiries, contacting local veterans organizations in the United States.

When he took the call Jan. 17 at VFW Post 25, post commander Jim Kuchwara misunderstood at first, wondering who was calling him from Jermyn. No, he was told, not Jermyn — Germany.

He contacted a couple of Prokop families who were not related to the airman before another veteran remembered receiving an email about Joseph Prokop three years ago while collecting the names of servicemen for inclusion on a monument at Scranton Veterans Memorial Park that Post 25 will help dedicate in July.

The email, which was sent by Spearmint, included her phone number.

Kuchwara said he called Spearmint and told her about the Hanau commemoration before gently breaking the news about what the city’s historians had learned about her brother’s death.

“She was quiet for a little bit,” he said. “It was emotional.”

Kuchwara, who has since met with Spearmint and other family members, said he anticipates representatives of the German government will attend the remembrance service at Cathedral Cemetery. The post is also trying to arrange for the ceremonies in Scranton and Hanau to be livestreamed between the cities.

Hanau deserves credit for honoring Prokop and the other airmen instead of sweeping a dark episode in its history under the rug, Kuchwara said.

“They could have brushed this off, but they are trying to make everything right,” he said.

Although Hanau has invited the Prokop family to send a representative the Feb. 17 plaque dedication, it was unclear as of last week whether anyone will make the trip to Germany.

Spearmint said the details about her brother’s death leave her with many questions. One thing she’d like to know is why the military never shared those details with her family.

“Why didn’t they tell us what happened then?” Spearmint asked. “They would have known.”

Spearmint, whose brothers John and Frank also served in World War II, said she wishes the full story had been revealed earlier.

All of her siblings deserved to know the truth about their brother Joe, she said.

“I never thought I’d live this long, and I kept asking why,” Spearmint said softly. “I think this is the reason — for me to find out about him.”