The Air Force has deployed dozens of nurses to hospitals throughout North Dakota and El Paso, Texas, to ease the strain on local medical personnel trying to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

For those airmen, like registered nurse Capt. Michael Robbins, it means lengthy, 12-hour-plus shifts in full protective equipment. It means caring for patients ― mostly elderly — by providing everything from baths to oral care to clearing their airways. And it means dropping into an entirely new workplace, with life-or-death stakes, and quickly becoming part of an already established team.

But while it’s hard work, Robbins feels privileged to be able to care for these patients.

“We’re just so proud and honored to be here, locked arm-in-arm with the North Dakota health care team,” Robbins said.

RELATED

Last month, as the latest, devastating wave of the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, the military deployed roughly 120 Air Force medical personnel — primarily nurses — to hot spots at the request of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

On Nov. 6, U.S. Army North announced that three Air Force Medical Specialty Teams had begun deploying that day to El Paso to support three hospitals there: the University Medical Center of El Paso, the Hospitals of Providence Transmountain Campus, and the Las Palmas Del Sol Medical Center.

Each team consists of 20 medical providers and a handful of administrative personnel from Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland in Texas, Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, Joint Base Andrews in Maryland, and elsewhere, ARNORTH said.

Nearly two weeks later, on Nov. 19, ARNORTH said the medical operation had expanded to four cities in North Dakota. Another 60 medical personnel — critical care nurses and medical-surgical nurses — were sent to the Essentia Health-Fargo and Sanford Medical Center in Fargo, the CHI St. Alexius Health Medical Center and Sanford Medical Center in Bismarck, Altru Hospital in Grand Forks, and Trinity Hospital-St. Joseph’s in Minot. Some of those personnel also came from Lackland, Eglin, Keesler and Andrews, though others also came from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio and Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Virginia.

Robbins, a critical care nurse who is part of the 96th Medical Group at Eglin, has been working in the critical care unit at St. Alexius in Bismarck about a week and a half ago, along with about 11 other Air Force nurses. When the call came to the 96th, looking for members to come to North Dakota and help with the coronavirus fight, Robbins stepped forward. It is his first deployment to assist with the pandemic.

Treating COVID was a fairly new experience for Robbins. He recently finished a 12-month critical care training program in which he learned how to provide care for COVID patients. And about a month before he deployed, he got the opportunity to treat coronavirus patients firsthand.

During the three night shifts he worked during his first week-and-a-half in Bismarck — he was about to begin his fourth shift when he spoke with Air Force Times — Robbins said he’s seen a lot of patients with respiratory issues. Some of them have experienced such serious decline that they’re on ventilators.

Some of the patients he’s seen with less-serious cases of COVID have improved to the point that they’ve been able to leave the hospital, Robbins said, and fortunately, he hasn’t lost any patients. But so far, the hospital’s doctors are being particularly cautious with ventilated patients and haven’t felt it’s safe enough yet to take any of the patients he’s treated off the ventilators.

The shifts are pretty standard for nurses — 12 hours, plus another 30 to 45 minutes beforehand to get “the lay of the land” and background on the two patients he’ll be responsible for that day, he said. That’s how many patients critical care nurses typically are responsible for, he added.

Sometimes at the beginning of his shifts, the nurse coming off-duty will take him by a patient’s bedside if there’s something he needs to see in person. Then, Robbins dives into the patients’ charts to see what medications they’re on and what time those meds are due, to plan out his day.

Then he does an assessment of his patients, to check their vital signs and make sure there are no changes that doctors need to know about.

Nurses also usually bathe patients during the night shift, Robbins said — not only to prevent infection, but also to help them feel cared for.

“This gives the patient a sense, even though they’re intubated and sedated, they do get a sense of feeling like they’re human, even though they’re not fully awake,” he said.

Robbins praised the staff at St. Alexius for making it easy for the Air Force nurses to join their team right away, and said they work well together. The previous night, he said, the nurses went room-to-room as a team and knocked out all the patients’ baths together in about two hours.

“The teams work like a pit crew,” he said. “Everyone I’ve met there is just so thankful that we’re here to help support the fight.”

The “bundles” of various treatments used to help COVID-19 patients have changed over the past few months, as the science behind the disease has become better known, Robbins said.

For example, “meticulous” oral care is important to cut down on a ventilated patient’s chances of developing pneumonia, Robbins said. The nurses use specialized toothbrushes and specialized oral solutions that has an anti-microbial effect to reduce cases of pneumonia.

The nurses also make sure to turn the patients side-to-side, so they don’t lay in one position for too long. Not only does that reduce the chances of bedsores that can become infected, Robbins said, it also helps clear the lungs out and move around anything that may linger there.

Nurses also check to make sure the ventilator settings are correct and all the tubes are in the right place and secure, so they don’t accidentally fall out. And if the nurses know a patient has something in their airways, they suction it out to clear the way for as much oxygen as they need.

The nurses also work hand-in-hand with respiratory therapists, and call them in if they need specialized help with a patient.

After his shift, Robbins typically sticks around another half-hour or more to bring the oncoming nurse up to speed, and ensure his patients receive consistent care, ending his shift at least 13 hours after he first arrived.

He said he’s so far cared for six COVID patients, most of whom were older.

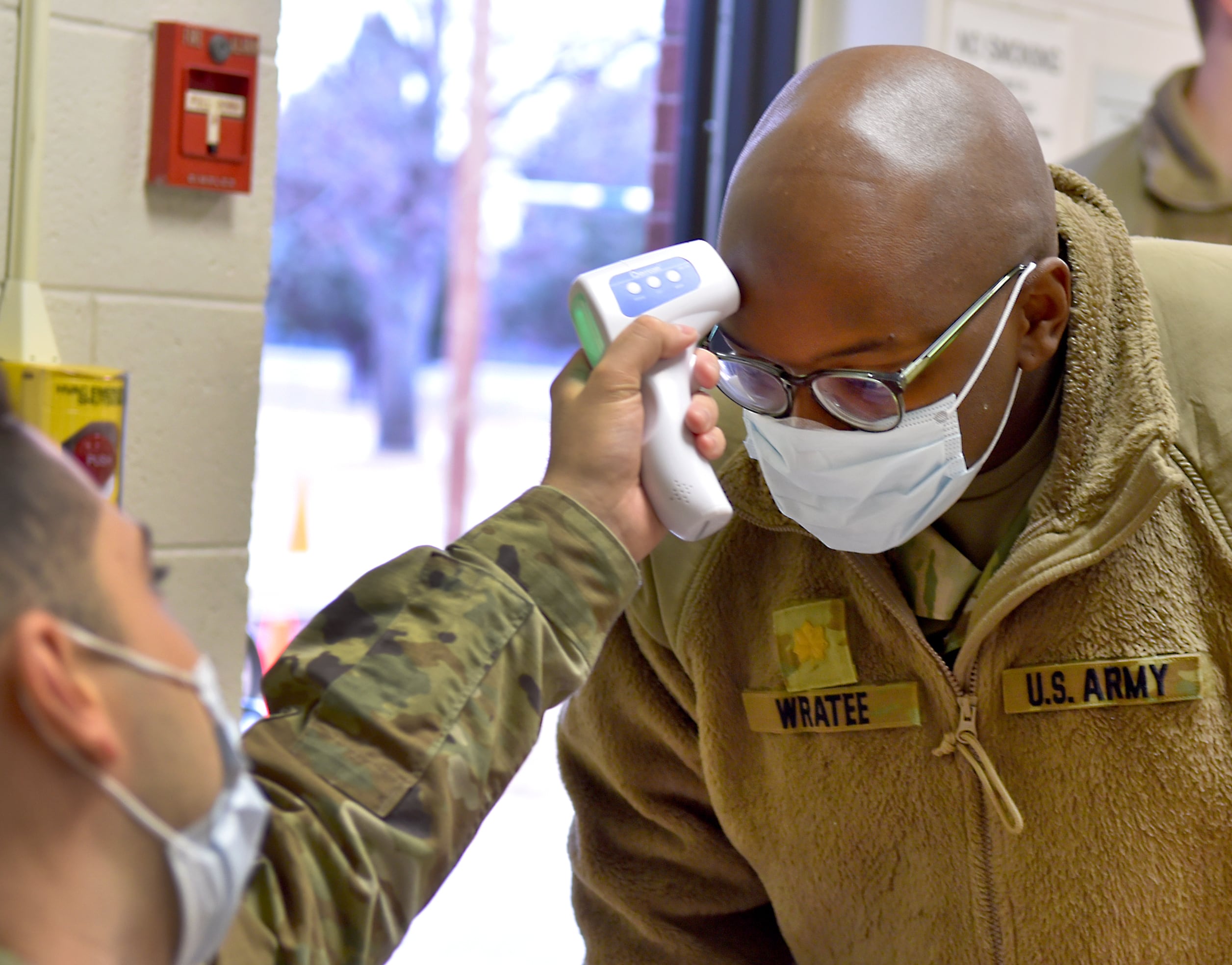

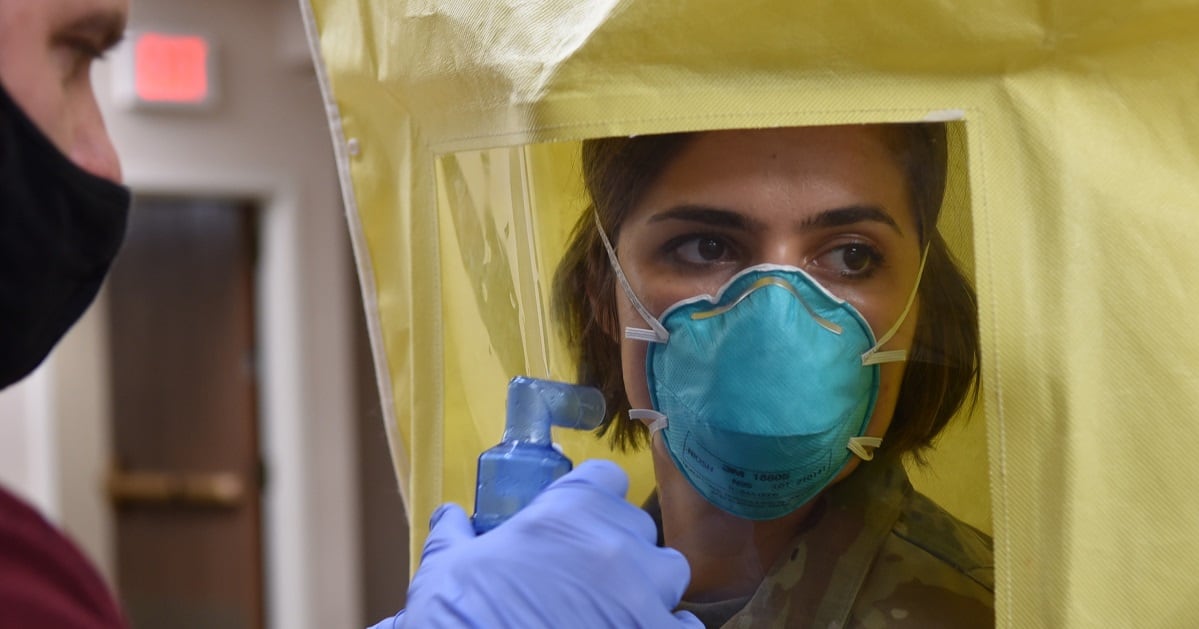

Ensuring the health and safety of the medical personnel is a top priority for the hospital’s leadership, Robbins said. So at all times in the COVID unit the nurses suit up with protective equipment, including N95 face masks with a surgical mask over it, eye protection such as goggles or face shields, a “bouffant” skull cap that covers their hair, gown, gloves and shoe coverings.

When it’s time for breaks, they remove all that equipment with care, sanitize themselves, and put on a fresh surgical mask. They’re allowed to take a few short breaks throughout their shift, Robbins said — though to avoid going through the process of taking off and then putting back on all that gear several times, some nurses skip breaks and take a single, long lunch.

The Bismarck community has been supportive. The local hotel housing Robbins and other nurses gave them care packages to show their appreciation.

And while there hasn’t been a lot of socializing, he said, sometimes the hospital staff takes the Air Force nurses out for a socially distanced meal.

“They take us out just to get to know us and, again, to welcome us as part of their own effort — especially after a long shift, arm-in-arm and side-by-side,” Robbins said.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.