Co-published with FRONTLINE .

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This story is part of a collaboration between ProPublica, Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program and FRONTLINE that includes the documentary American Insurrection, that aired on PBS.

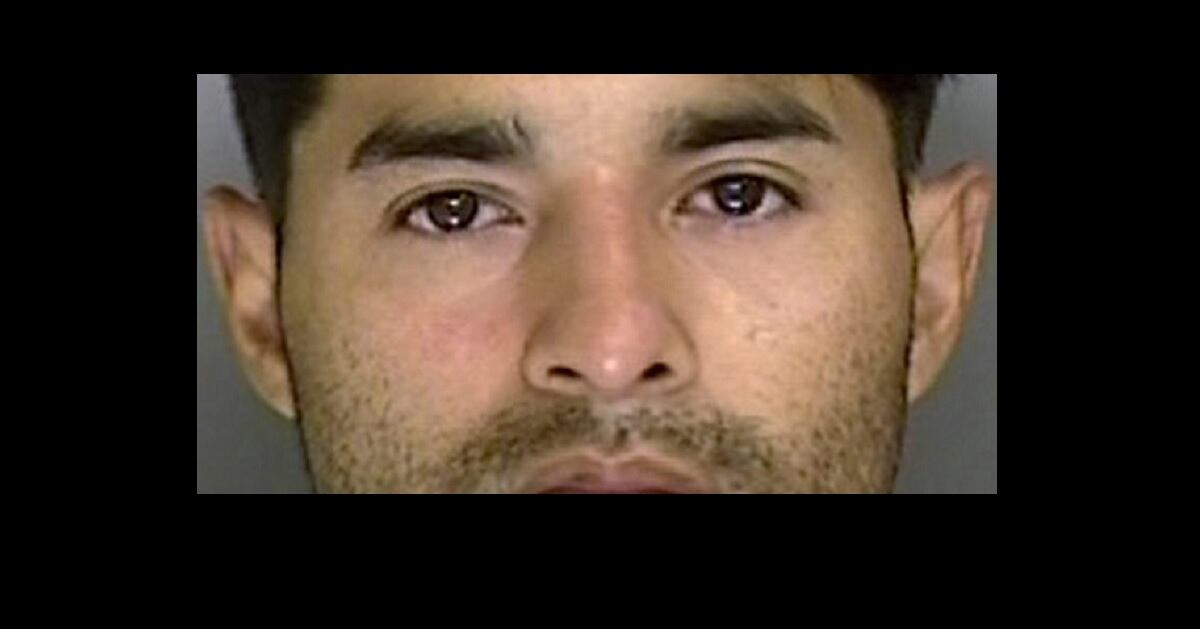

It was 2:20 p.m. on June 6, 2020, and Steven Carrillo, a 32-year-old Air Force sergeant who belonged to the anti-government Boogaloo Bois movement, was on the run in the tiny mountain town of Ben Lomond, California.

With deputy sheriffs closing in, Carrillo texted his brother, Evan, asking him to tell his children he loved them and instructing him to give $50,000 to his fiancée. “I love you bro,” Carrillo signed off. Thinking the text message was a suicide note from a brother with a history of mental health troubles, Evan Carrillo quickly texted back: “Think about the ones you love.”

In fact, Steven Carrillo had a different objective, a goal he had written about on Facebook, discussed with other Boogaloo Bois and even scrawled out in his own blood as he hid from police that day. He wanted to incite a second civil war in the United States by killing police officers he viewed as enforcers of a corrupt and tyrannical political order — officers he described as “domestic enemies” of the Constitution he professed to revere.

Now, as he texted with his brother and watched deputies assemble so close to him that he could hear their conversations, Carrillo sent an urgent appeal to his fellow Boogaloo Bois. “Kit up and get here,” he wrote in a WhatsApp message that prosecutors say he sent to members of a heavily armed Boogaloo militia faction he had recently joined. The police, he texted, were after him.

“Take them out when theyre coming in,” the text read, according to court documents.

Minutes later, prosecutors allege, Carrillo ambushed three deputy sheriffs, opening fire with a silenced automatic rifle and hurling a homemade pipe bomb from a concealed position on a steep embankment some 40 feet from the deputies. One deputy was shot dead, and a second was badly wounded by bomb shrapnel to his face and neck. When two California Highway Patrol officers arrived, Carrillo opened fire on them, too, police say, wounding one.

“The police are the guard dogs, ready to attack whenever the owner says, ‘Hey, sic ‘em boy,’” Carrillo said in an interview, the first time he has spoken publicly since he was charged with murdering both the deputy sheriff in Ben Lomond and, a week earlier, a federal protective security officer at the Ronald V. Dellums Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse in Oakland.

When Carrillo was finally subdued on June 6, cellphone footage captured him shouting at deputies as they led him away, “This is what I came to fight — I’m sick of these goddamn police.”

For Carrillo, that final frenzied expression of rage marked the culmination of a long slide into extremism, a journey that had begun a decade earlier with his embrace of the tea party movement, libertarianism and Second Amendment gun rights, before evolving into an ever-deepening involvement with paramilitary elements of the Boogaloo Bois. The militant group is known for the distinctive Hawaiian shirts its members wear at protests, often while brandishing AR-15s and agitating for the “Boog” — the group’s shorthand for civil war.

Carrillo’s arrest was also an omen of something larger and even more ominous: the rise of a violent insurrection movement across America led by increasingly extreme and aggressive militias that seek out opportunities to confront and even attack the government. Examples of this broader insurrection abound, from October’s foiled plot to abduct Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to the leading role militia groups such as the Proud Boys and Oathkeepers played in the violent takeover of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

While militias have long been active in the United States, groups tracking extremist violence have reported notable increases in paramilitary activity over the past year, and the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the director of national intelligence have all issued stark warnings in recent months about an elevated threat of violence from domestic extremist groups.

ProPublica, Frontline and Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program also uncovered new evidence that some military service members have embraced extremist ideology. The news organizations identified 15 active-duty members of the Air Force who, like Carrillo, openly promoted Boogaloo memes and messages on Facebook. On April 9, the Pentagon announced new measures to combat extremism inside the military. The Biden administration, meanwhile, is increasing funding for preventing attacks by militias, white supremacists and other anti-government groups, The New York Times reported this month.

RELATED

“These groups want to be instigators, the frontline of the civil war that is going to happen in this country,” said John Bennett, who was the special agent in charge of the FBI’s San Francisco Division at the time of Carrillo’s arrest.

“The scary thing,” he added, “is a lot of people in these groups that we’re seeing now are your neighbors.”

An examination of Carrillo’s life and his path to radicalization, based on extensive interviews with him, his family, his friends and his fiancée, along with a review of hundreds of pages of court records, previously undisclosed text messages and internal militia documents, revealed startling new details about the threat posed by the Boogaloo Bois.

Experts in extremist militia groups have long regarded the Boogaloo Bois as having no real hierarchy or leadership structure. But in piecing together Carrillo’s activities and militia contacts, law enforcement officials were stunned to discover the extent of coordination, planning and communications within the group.

Not only was Carrillo in regular contact with a wide range of prominent Boogaloo Boi figures around the country, records and interviews show, but two months before his arrest Carrillo had joined up with a heavily armed, highly organized and extremely secretive Boogaloo militia group in California that called itself the “Grizzly Scouts.”

“This group was different,” Jim Hart, the sheriff of Santa Cruz County, where Ben Lomond is located, said in an interview. “There was a definite chain of command and a line of leadership within this group.”

In a federal indictment unsealed on April 9, prosecutors said Carrillo and four members of the Grizzly Scouts, including its leader, “discussed tactics involving killing of police officers and other law enforcement.” The indictment also alleges that the same four Grizzly Scouts tried to thwart a criminal investigation into their activities by destroying evidence of their communications with Carrillo and each other.

In nearly two hours of interviews conducted in Spanish and English, as well as in a letter dictated to his fiancée from Santa Rita Jail east of Oakland, Carrillo talked about the evolution of his anti-government ideology. While he would not discuss any of the criminal charges against him, Carrillo spoke at length about his continuing allegiance to the Boogaloo Bois and patiently explained how the movement’s “revolutionary thought” could offer a rationale for attacks against law enforcement officers who he or any other Boogaloo Boi thinks are violating the Constitution. “I pledged to defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic,” he said.

Not once did Carrillo express pity or remorse over the deaths of Sgt. Damon Gutzwiller, the deputy sheriff, whose wife was pregnant with their second child, or David Patrick Underwood, the security officer at the Oakland federal building, who made a habit of donating to local baseball youth organizations.

Becoming a Boog

Born in Los Angeles in 1988, Carrillo had an early childhood marked by episodes of domestic violence. According to family members, his father, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who worked as a tree trimmer, repeatedly assaulted his mother, who was from Burbank, California.

Given up by his parents as a toddler, Carrillo, along with his older brother, Evan, were taken in by other members of their family, and at age 5 he was sent with his brother to a tiny rural village in Jalisco, Mexico, where they lived on their grandparents’ farm. A couple of years later, the Carrillo boys returned to California to live with their father, eventually settling in Ben Lomond, a remote two-stoplight town in the Santa Cruz Mountains. After graduating from San Lorenzo Valley High School, Carrillo said he joined the Air Force in 2009, the same year he married his childhood sweetheart. In an interview, Carrillo’s father denied the family’s allegations of domestic violence, but otherwise declined to comment. Carrillo’s mother would not speak on the record for this article.

According to Carrillo, his ideas about politics and the role of government began to take shape in the Air Force. “Before, I was confined to a little bubble,” he said in an interview, referring to his upbringing in Ben Lomond, population 7,000. Once he joined the Air Force and met others from around the world, “talking to people changed my whole views,” he said. He followed a well-worn path that began with a fierce attachment to gun rights, which in turn led him to libertarianism, and then an enthusiastic embrace of the tea party movement.

By 2012, Carrillo was a registered Republican who supported Gary Johnson, the presidential candidate of the Libertarian Party, and Ron Paul. He attended Second Amendment rallies and advocated for expanded gun rights on a Facebook page set up for a group of self-described Christian “patriots.”

In 2015, while stationed at Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah, Carrillo was in a car accident that left him hospitalized with a concussion and head lacerations. Family and friends said the crash affected his mental health. “He wasn’t himself,” Evan Carrillo said in an interview. “He was usually very talkative, very social. I was the quiet one. And now it was like talking to a wall.”

At the time, Carrillo was a security forces officer in the Air Force. According to his siblings, his mental health issues were serious enough that the Air Force took Carrillo’s gun away for several months. (The Air Force said it could not immediately locate the records it needed to comment about this incident.)

He became even more withdrawn, family members said, after his wife committed suicide in 2018, shortly after he confessed to cheating on her yet again. He spoke of wanting to kill himself and started living out of a van, leaving it to his in-laws to look after his two young children. “He was just in complete disconnect of how people should live and who he was,” said his sister, Ruby.

And yet months after his wife’s suicide, Air Force records show, Carrillo was serving as an apprentice in Phoenix Raven, an elite Air Force security unit that is dispatched to protect aircraft and air crews in global hotspots. At the time, Carrillo was stationed at Travis Air Force Base in Northern California, but his apprenticeship with the Ravens also gave him special training in combat techniques, explosives and advanced firearms proficiency at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst near Trenton, New Jersey.

According to the Air Force, Carrillo completed the 24-day Phoenix Raven qualification course in New Jersey in late 2018, then returned to Travis Air Force Base to become “fully mission qualified as a Raven.” From July to November of 2019, Carrillo served as a Phoenix Raven team leader in Kuwait and other countries in the region, the Air Force said.

In an interview, Carrillo said he was introduced to the political ideology of the Boogaloo Bois through friends in the Air Force and on the internet. The 15 active-duty airmen identified by the news organizations as openly promoting Boogaloo content on Facebook worked at bases around the world, including eight who, like Carrillo, served in the Air Force security branch.

When asked about these active-duty airmen, the Air Force said in a statement that personnel who participate in extremist groups are in “direct violation” of Defense Department regulations. “Supporting extremist ideology, especially that which calls for violence or the deprivation of civil liberties of certain members of society, violates the oath every service member takes to support and defend the Constitution of the United States,” the Air Force statement said.

On April 9, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin ordered the Pentagon to take a series of immediate steps to counter extremism in the military.

It is unclear precisely when Carrillo began associating with the Boogaloo Bois, but according to a sworn statement from an FBI agent he was in direct contact with prominent figures in the group by December 2019.

The next month, prosecutors allege, he bought a $15 device that converts AR-15 semiautomatic rifles into fully automatic machine guns, making the purchase through a website that advertised to Boogaloo Facebook groups and promised to donate some of its profits to the family of Duncan Lemp, who became a Boogaloo martyr after he was killed in a police raid. Carrillo also began incorporating popular militia memes and imagery into his Facebook posts, and was in touch online with a growing circle of Boogaloo Bois. “A lot of people in the movement knew who Steve was,” Mike Dunn, the leader of a Boogaloo faction in Virginia that calls itself the Last Sons of Liberty, said in an interview.

Carrillo’s girlfriend, Silvia Amaya, said she noticed a distinct shift in Carrillo’s behavior at around this time. He struggled with insomnia and was increasingly “shut off in his own world,” she said in an interview. He talked frequently about how “a war would start soon,” echoing the core belief of Boogaloo followers.

The Grizzly Scouts

On March 14, 2020, prosecutors allege in court filings, Carrillo received a text message from Ivan Hunter, a Boogaloo Bois leader in Texas. The message reads like an instruction to get ready for action. “Start drafting that op,” Hunter wrote to Carrillo. “The one we talked about in December. I’ma green light some shit.” In response, Carrillo wrote, “Sounds good, bro!” Soon after, Carrillo sought to join the Grizzly Scouts, a newly formed California militia group that had proclaimed its “affinity for Hawaiian shirts,” the best-known symbol of the Boogaloo Bois, in its profile page on mymilitia.com.

The Grizzly Scouts, also known as the 1st Detachment of the 1st California Scouts, are based in Turlock, a small city about 100 miles southeast of San Francisco. According to federal prosecutors, the Grizzly Scouts had a Facebook group called “/K/alifornia Kommando” that proclaimed their desire “to gather like minded Californians who can network and establish local goon squads.” (Among the Boogaloo Bois, the word “goon” refers to a single member.)

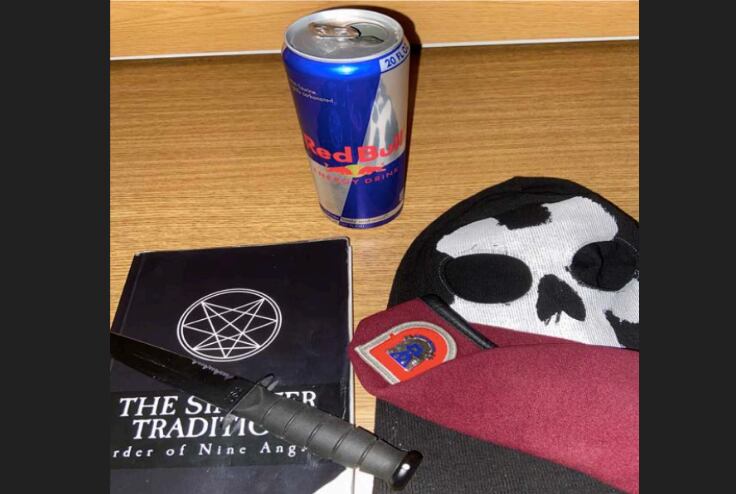

On April 10, 2020, according to records obtained by the news organizations, a member of the Grizzly Scouts who goes by the alias BoojerBro1776 emailed Carrillo an extensive packet of application materials, 31 pages in all. (“On boarding,” read the email’s subject line.) The documents, never before publicly disclosed, are an odd blend of corporate instruction manual and chilling playbook for armed military action.

New recruits were asked to abide by a social media policy and to sign both a non-disclosure agreement and a release of liability. The application itself offered this bit of corporate boilerplate: “If this application leads to employment, I understand that false or misleading information in my application or interview may result in my release.”

At the same time, the documents make clear that the Grizzly Scouts intended to do more than simply meet up in the woods for occasional target practice. A policy on the Grizzly Scouts’ dress code begins this way: “Since the time man realized we could kill each other to gain something, men have donned uniforms and have gone to battle.” The documents, which describe the Grizzly Scouts as an “armed Constitutional militia,” go on to decree that black will be worn “while conducting covert/clandestine operations,” and stress the importance of wearing approved Grizzly Scout uniforms “to mitigate any potential battlefield confusion.”

“Our Areas of Operations can take us from the dirt to downtown in a blink of an eye,” the document states.

The documents also make clear that Carrillo’s military background, in particular his advanced combat and weapons training, provided exactly the qualities the Grizzly Scouts wanted in its recruits. The Grizzly Scouts’ members — law enforcement officials say the group had attracted 27 recruits — were given military ranks and roles based on their level of military training and prior combat experience. Some Grizzly Scouts were designated “snipers,” others were assigned to “clandestine operations,” and some were medics or drivers. Whatever their role, all were expected to maintain go kits that included “combat gauze” and both a “primary” and “secondary” weapon.

Two weeks after receiving his application materials, Carrillo joined the Grizzly Scouts for a weekend of training — or “church,” in the group’s vernacular. In keeping with the Grizzly Scouts’ desire for secrecy, Carrillo was vague with Amaya, his girlfriend, about where he had been and whom he was with. Aware of his history of cheating, Amaya imagined the worst and insisted he take her along the next time he planned to meet with his mysterious new friends. “I was very angry and jealous,” she said.

On May 9, the couple loaded their car with guns and bulletproof vests and headed toward a ranch in Mariposa County, not far from Yosemite National Park, to meet the Grizzly Scouts for another training session. Along the way they met up with Jessie Rush, the “detachment commander” of the Grizzly Scouts, whose LinkedIn profile says he is a U.S. Army veteran now employed by a private security company. Rush, also known as “Grizzly Actual,” reminded them not to take photos, but otherwise raised no objections to Amaya’s presence as the Grizzly Scouts went through various shooting drills.

Rush, one of the four Grizzly Scouts now charged with concealing evidence of their communications with Carrillo, declined to comment.

When asked in an interview about his involvement with the Grizzly Scouts, Carrillo responded evasively. “How did you figure that out?” he asked in Spanish when first pressed about his ties to the group. Later, Carrillo professed little understanding of either the aims or activities of the Grizzly Scouts. “We were just getting to know each other,” he said.

According to prosecutors, however, Carrillo held the rank of “staff sergeant” in the Grizzly Scouts, and, as with other members of the group, he was given an animal nom de guerre: “Armadillo.”

Combat mode

George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis on May 25, 15 days after Carrillo’s last training session with the Grizzly Scouts, galvanized the Boogaloo faithful. In online postings, they spoke of Floyd’s death not only as an example of egregious police misconduct but as an opportunity to stoke chaos that could be blamed on the Black Lives Matter movement. The resulting racial unrest, they hoped, would accelerate the long-awaited “Boogaloo” — the final conflict, a second Civil War.

Two days after Floyd’s death, Carrillo’s Boogaloo friend Ivan Hunter drove from Texas to Minneapolis. Armed with an AK-47-style semiautomatic rifle, Hunter fired off 13 rounds into an abandoned Minneapolis police precinct where hundreds of protesters had gathered, prosecutors allege. Prosecutors say Hunter yelled, “Justice for Floyd!” before disappearing into the night with several other Boogaloo Bois who had come to Minneapolis to provoke civil strife. Hunter, eventually arrested in San Antonio, was charged with participating in a riot and is being held without bail; his defense lawyer declined to comment.

For Carrillo, Floyd’s death confirmed his view of the police as little more than willing instruments of a corrupt and tyrannical political order bent on destroying the Constitution. “I felt hate more than anything,” he said in an interview when asked about Floyd’s killing.

“The Boogaloo revolution is against the government,” he explained, “but the police is basically the government’s dog on a leash.”

Amaya said Floyd’s killing “unleashed the worst” in Carrillo, who in the days that followed behaved, she recalled, like a man who was preparing for battle. “It’s a great opportunity to target the specialty soup bois,” Carrillo wrote on his Facebook page on May 28, using Boogaloo slang for federal law enforcement agencies. That night he shocked Amaya by proposing marriage, presenting her with a $25 turquoise blue silicone ring and promising to replace it with a diamond ring later.

The next day, Carrillo left Amaya’s house. According to prosecutors, he picked up another Boogaloo Boi, Robert Justus Jr., and drove to downtown Oakland. It was 9:15 p.m., and crowds had gathered on Oakland’s streets to protest and mourn Floyd’s death. Meanwhile, blocks away, the two men drove a white Ford van around Oakland’s federal courthouse, where David Patrick Underwood, a federal protective security officer, staffed a two-person guard hut. Prosecutors say Carrillo was in the back seat near the sliding door, carrying a short-barreled rifle, a “ghost weapon” with no serial number, making it almost impossible to trace. According to the FBI, it was an illegal machine gun optimized to fire bursts of shots automatically, with an added silencer.

Hours before, Carrillo had posted on Facebook that if “it’s not kicking off in your hood then start it.” Now, according to prosecutors, Justus drove toward the guard hut while Carrillo slid the van’s door open and fired multiple bursts, killing Underwood and seriously wounding a second guard. “Did you see how they fucking fell” Carrillo said as the van drove off, according to an account Justus gave investigators after turning himself in.

“In his mind, Steven was on a mission just like in the Air Force, except the enemy was the police,” Amaya said.

An image captured by a surveillance camera during the shooting at Oakland’s federal courthouse on May 29, 2020, shows the white van’s door open as Carrillo allegedly fired at officers in a guard hut, far right. Credit:United States District Court for the Northern District of California

A lawyer for Justus, who has been charged with aiding and abetting Underwood’s murder, declined to discuss his client’s alleged involvement with the Boogaloo Bois. Instead he pointed to court filings that describe what Justus told investigators. According to those records, Justus insisted to investigators that he felt he had to participate because he was “trapped in the van.” He also claimed he told Carrillo, “I am not cool with this,” and tried to think of ways to “talk Carrillo out of his plan,” only for Carrillo to respond by pointing a rifle at him and asking if he was “a cop or a rat.”

The shooting of both guards aligned neatly with Boogaloo ideology. “Use their anger to fuel our fire,” Carrillo had written on Facebook that morning. “We have mobs of angry people to use to our advantage.” Sure enough, some conservative commentators rushed to blame Underwood’s murder on antifa and Black Lives Matter protesters.

Four hours after Underwood’s death, Carrillo received a text message from Hunter urging him to attack police buildings, court records show.

Carrillo’s response: “I did better lol.”

That weekend, when Carrillo returned to Amaya’s house, he seemed “on edge and distracted,” she recalled. He asked for a week’s leave at Travis Air Force base and sent $200 to Hunter, congratulating him for “doing good shit out there.” Most of the time, she said, Carrillo was glued to Facebook, following the news and commenting on viral videos of police clashing with protesters. “Who needs antifa to start riots when the police do it for you,” read one of his posts.

In the days after the Oakland shooting, Carrillo communicated regularly with Rush and other members of the Grizzly Scouts on a WhatsApp group they called “209 Goon HQ,” prosecutors say. (The area code for Mariposa County, home turf of the Grizzly Scouts, is 209.) Via WhatsApp, they repeatedly made references to the “Boog” and “discussed committing acts of violence against law enforcement,” prosecutors allege.

On Saturday, June 6, Carrillo drove to his father’s house in Ben Lomond. It was about 2 p.m. when Gutzwiller, a sergeant in the Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Office, and two more deputies arrived at the property, which was guarded by a dog wearing a bulletproof vest and monitored by security cameras. They were responding to a call from a passerby who had spotted a suspicious white Ford van loaded with what appeared to be firearms and bomb-making material. When the deputies learned the van was registered to Carrillo’s father, they pulled up to his house to question him.

The deputies did not realize Carrillo was above them, perched just 40 feet away in a covered, well-concealed position up a steep embankment, aiming the same “ghost” weapon that prosecutors say he had used in Oakland.

Based on the WhatsApp text messages that prosecutors say he sent at this time, Carrillo appeared to be trying to guide his fellow Grizzly Scouts on how they could join forces with him in a coordinated attack on the law enforcement officers gathering to search for him.

“Theyre waiting for reenforcements,” he texted.

And this: “Theres inly one road in/out. Take them out when theyre coming in.”

According to police, Carrillo “sniped” Gutzwiller, killing him with a single shot to the chest. Another deputy was also shot in the chest, but was saved by his bulletproof vest.

During the mayhem and bloodshed that followed, Carrillo engaged in a running gun battle with law enforcement officers, hurling pipe bombs and hijacking vehicles. In his own blood, he scrawled “BOOG” and “I became unreasonable” and “Stop the Duopoly” — all common Boogaloo slogans — on the hood of a car he had stolen. And at some point, he sent one more WhatsApp message to his fellow Grizzly Scouts: “Dudes i offed a fed.”

For all of Carrillo’s urgent appeals for reinforcements, there is no indication any Grizzly Scout tried to come to his aid. While questioning Carrillo’s fiancée in August, Henry Montes, an investigator for the Santa Cruz County District Attorney’s Office, offered a possible explanation. Some members of the Grizzly Scouts, he said, had told investigators that Carrillo was too extreme for them. “The things that he was saying made them think he wants to kill policemen,” Montes told Amaya, according to a recording of the interview obtained by the news organizations.

“We spoke with some people who were no longer part of that group because they were afraid of Steven,” Montes said.

A jailhouse wedding

In interviews, Carrillo’s siblings describe a brother who suffered from years of severe mental health problems and didn’t get the support and medical treatment he needed from the Air Force. “I could see his pain,” Carrillo’s sister, Ruby, said.

Over two hours of interviews, Carrillo himself did not attribute any of his actions to mental illness. Instead, he forthrightly proclaimed his support for the Boogaloo Bois and repeatedly challenged what he views as misconceptions about the group.

“I just want to say, the Boogaloo movement, you know, there’s a lot in the paper that I feel like people don’t understand,” he said. “And that is the Boogaloo movement, it’s all inclusive. It includes everyone. It’s not a thing about race. It’s about people that love freedom, liberty, and they’re unhappy with the level of control that the government takes over our lives. So it’s just a movement, it’s a thought about freedom. It’s just a complete love for freedom.

Meanwhile, as Carrillo sits in jail awaiting trial, his political evolution continues. In a letter he wrote to reporters in October, he referred to Joe Biden as a man who “sniffs kids,” echoing QAnon, a pro-Trump conspiracy theory that falsely accuses the Democratic Party of running a Satan-worshipping child sex-trafficking ring.

Carrillo’s defense lawyers declined to comment.

Amaya continues to stand by Carrillo. “I know him, and I think he can change,” she said.

On Christmas Day the couple exchanged vows through a video call from the Santa Rita Jail. “I love your lips, baby,” Carrillo told her.

She promised to love him “forever and always.”

A.C. Thompson contributed reporting.