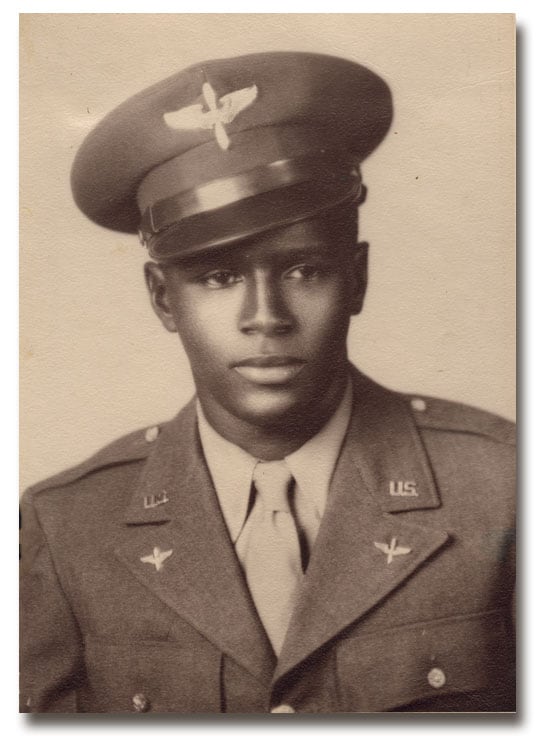

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—James Harvey doesn’t want to be known as the first Black fighter pilot to fly in Korean airspace. He doesn’t want to be known for his Distinguished Flying Cross or the 11 Air Medals he earned in combat. And he doesn’t want to be known for his time as a commander, a test pilot or an officer reporting to the head of NORAD.

Harvey, one of the few members of the Tuskegee Airmen still living, wants to be remembered for an honor that eluded the public eye for nearly 50 years: winner of the Air Force’s first aerial shooting competition in 1949.

The 98-year-old retired lieutenant colonel spoke to Air Force Times ahead of a Sept. 21 ceremony here to honor his legacy as a flying pro, hosted by AARP and Raytheon.

Harvey first imagined himself as a pilot as a child in Nuangola Station, a rural area outside of Wilkes-Barre in eastern Pennsylvania.

“I sat in my front yard, and I saw this flight of P-40s fly over in formation,” he said. “I said, ‘I’d like to do that one day.’”

He said he tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps in January 1943, as World War II was in full swing. Despite the impending Allied invasions of Axis-controlled North Africa, Italy, France and others, the military turned him down.

“They said they weren’t taking enlistments at that time,” he said. He believes it was because he is Black.

Still, Harvey was drafted into the Army a few months later. He headed first to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, for basic training and then to engineer training, where he learned to bulldoze and set up airfields in the jungle. But he still wanted to be in a cockpit.

He reapplied to become an aviator and completed the exam at Washington’s Bolling Field to attend pilot training school.

“There were 10 of us that took the exam: nine whites and myself. Two of us passed,” Harvey said.

He became one of about 1,000 Black men trained in Tuskegee, Alabama, from 1941 to 1946 who were the first African American military pilots in American history. The Tuskegee Airmen encompassed more than 14,000 Black men and women who worked in a range of aviation and office jobs in those squadrons and groups, and others who were stationed at their bases.

Joining the segregated military gave Harvey his first taste of racism, he said. With no desire to participate in the growing civil rights movement and no television to watch it at home, Harvey waged his own campaign to be seen as equal inside the Army Air Corps.

The self-described perfectionist and loner talks about his military service in simple terms: “I’m out there to do my job the best I can.”

That yielded a career in 12 aircraft over 22 years: the PT-19, BT-13, AT-6 and T-33 training planes; the early propeller-driven P-40, P-47 and P-51 fighters and bombers; and the jet-powered F-80, F-86, F-89, F-94 and F-102 fighters, according to Harvey’s personal website.

He learned to fly at Moton Field and what is now known as Sharpe Field, Alabama, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. After graduating as a second lieutenant in October 1944, Harvey flew P-47 Thunderbolts with the 99th Fighter Squadron at Godman Army Airfield, Kentucky.

Despite the 99th’s earlier support in Allied operations across Europe and North Africa, Harvey never got the chance to head to Europe or Japan before World War II ended in 1945, according to the VA.

In 1949, however, the recently formed Air Force convened a new kind of competition: an air-to-air and air-to-ground gunnery meet at what is now Nellis AFB, Nevada, with separate events for conventional-engine and jet-powered planes. It was later replaced by the “Gunsmoke” and “William Tell” competitions.

Each fighter group was directed to hold a shoot-off and pick the three highest-scoring pilots to represent them in the first-ever contest, nicknamed “Top Gun,” Harvey said. The 332nd Fighter Group at the former Lockbourne AFB, Ohio, tapped Capt. Alva Temple of the 301st Fighter Squadron, 1st Lt. Harry Stewart of the 100th Fighter Squadron, and Harvey to participate, with 1st Lt. Halbert Alexander of the 99th as an alternate.

Their competitors flew more-advanced P-51 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs against the Tuskegee Airmen’s older P-47s in events ranging from aerial gunnery at 12,000 and 20,000 feet to dive bombing, low-altitude skip bombing, rocket firing and panel strafing, according to a 2012 Air Force release.

“Capt. Temple scored six for six, Stewart scored six for six, and I scored six for six” on skip bombing, Harvey said in the release. “The next day was rocket firing; Temple had six for six, Stewart had five for six, and I had five for six.”

The Black pilots led after both aerial gunnery events and faltered during the dive bombing portion, but maintained their lead long enough to win the inaugural Fighter Gunnery Award trophy for conventional aircraft. Then their victory faded into history, according to Harvey.

Harvey said Air Force-related records, like the Air Force Association’s annual almanac, failed to list their achievement. For example, the 1996 almanac lists Lt. Calvin Ellis from Langley AFB’s 4th Fighter Wing and Lt. William Crawford from the 332nd FW at Lockbourne as the 1949 Gunsmoke winners.

Ellis is inscribed on the trophy as a jet-class winner; Crawford isn’t on the trophy.

Stewart helped bring the information to light again in the 1990s so the Tuskegee airmen’s win would be properly acknowledged, the service said in 2012.

The trophy disappeared from view for decades, Harvey said, but turned up in storage in the early 2000s and is now on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. It bears the names of Harvey and his teammates, the airmen who won the jet-class competition in 1949 and the two winning teams in 1950.

The trophy lists Temple as a major, Stewart as a captain and Harvey as a lieutenant.

Daniel Haulman, an expert on the Tuskegee Airmen with the Air Force Historical Research Agency, in 2016 offered an explanation for the trophy’s whereabouts all those years.

When the trophy was awarded for the last time before the Korean War paused the gunnery competitions, it went to the Smithsonian Institution, Haulman said. The Smithsonian couldn’t display all of the thousands of artifacts in its care, and ended up handing the trophy to the Air Force museum in Ohio after it became an official organization in 1975.

“Years later, largely through the efforts of Zellie Orr, the trophy for the Air Force’s gunnery meets in Las Vegas in 1949 and 1950 was put on display as part of an exhibit to commemorate the achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen, since the 332nd Fighter Group was its most famous organization, although the 332nd Fighter Group was not the only group to win the trophy,” Haulman said.

The 99th Fighter Squadron was desegregated and disbanded in July 1949, following President Harry Truman’s 1948 order to integrate the armed forces.

Later that year, Harvey deployed to Misawa Air Base in Japan to fly F-80 Shooting Stars — the first U.S. jet fighter — during the Korean War. There, he was named a flight commander before heading to now-closed George Air Force Base, California, to become an instructor and test pilot with the 94th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, according to his personal website.

By 1960, he had moved on to serve as a flying safety officer with NORAD, a fighter training officer at the now-defunct Northeast Air Command headquarters on the island of Newfoundland, Canada, and in leadership positions at the 1st Fighter Group and 71st Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Selfridge AFB, Michigan.

At the end of his military career, Harvey was assigned to another NORAD region headquartered at Truax Field, Wisconsin, working for the commanding general and his staff. He retired from military service in 1965.

In the corporate world, he climbed the ladder in sales at Oscar Mayer until retiring in 1980 as the company’s first Black distribution center manager in Denver, Colorado.

Eight decades after the Tuskegee Airmen made history, Harvey is glad to see another milestone: Gen. Charles “CQ” Brown’s start last year as the first Black Air Force chief of staff.

Asked what it means to him to see that barrier broken, Harvey grew upset. For him, the accomplishments of Brown and other Black generals are a reminder of what the Black community endured when a 1925 Army War College report declared them inferior to their white counterparts.

“All the congressmen had read the report, all the Army commanders had a copy of the report, and all that report did was reinforce the racist attitude that they had toward us,” Harvey said. “We had to overcome all that stuff, and we did.”

The report, released two years after Harvey was born but nearly two generations before Brown’s time, has been proven wrong again, the older man said.

Harvey has continued his efforts to educate the public about his winning Gunsmoke team as he outlives most other Tuskegee Airmen, including Alva Temple and Halbert Alexander. But he wants his legacy to be made of humble stuff: He did his best; he was kind; he had a sense of humor; he was a good person.

“If it comes, it comes,” he said of death. “But I expect to delay it … many more years.”

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.