A man who began hemorrhaging blood in midair after surgery.

An infant whose veins wouldn’t hold an adult-sized IV.

A woman with a precarious spinal cord injury.

Capt. Katie Lunning saved them all.

Her calm and skill under pressure that ensured 22 patients survived the suicide bombing at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan — and more than a dozen others in the days before — has earned Lunning, now a major, Military Times’ 2023 Airman of the Year award.

Lunning, 40, of Urbandale, Iowa, is the chief critical care nurse at the Minnesota Air National Guard’s 133rd Medical Group, and the intensive care unit nurse manager at the Iowa Department of Veteran Affairs.

The daughter of an Army veteran, Lunning enlisted in the Guard in 2002 to help pay for college and support the local communities where she was raised. She alternated between jobs in Air Force health service management and Army recruiting, and rose to the rank of staff sergeant in the Army Guard.

Then, Lunning set off on the same path as the nurses in her family before her. She returned to her health care job in the Air Guard in 2009, earned her bachelor’s degree in nursing from Bethel University in 2012, and was commissioned as an officer in 2013.

Her time as a nurse in the National Guard and in VA-run hospitals prepared Lunning for the emergency she would face nearly 10 years later, several thousand miles from home.

In June 2021, Lunning got the chance to deploy as a critical care air transport nurse with the 379th Expeditionary Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron to Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.

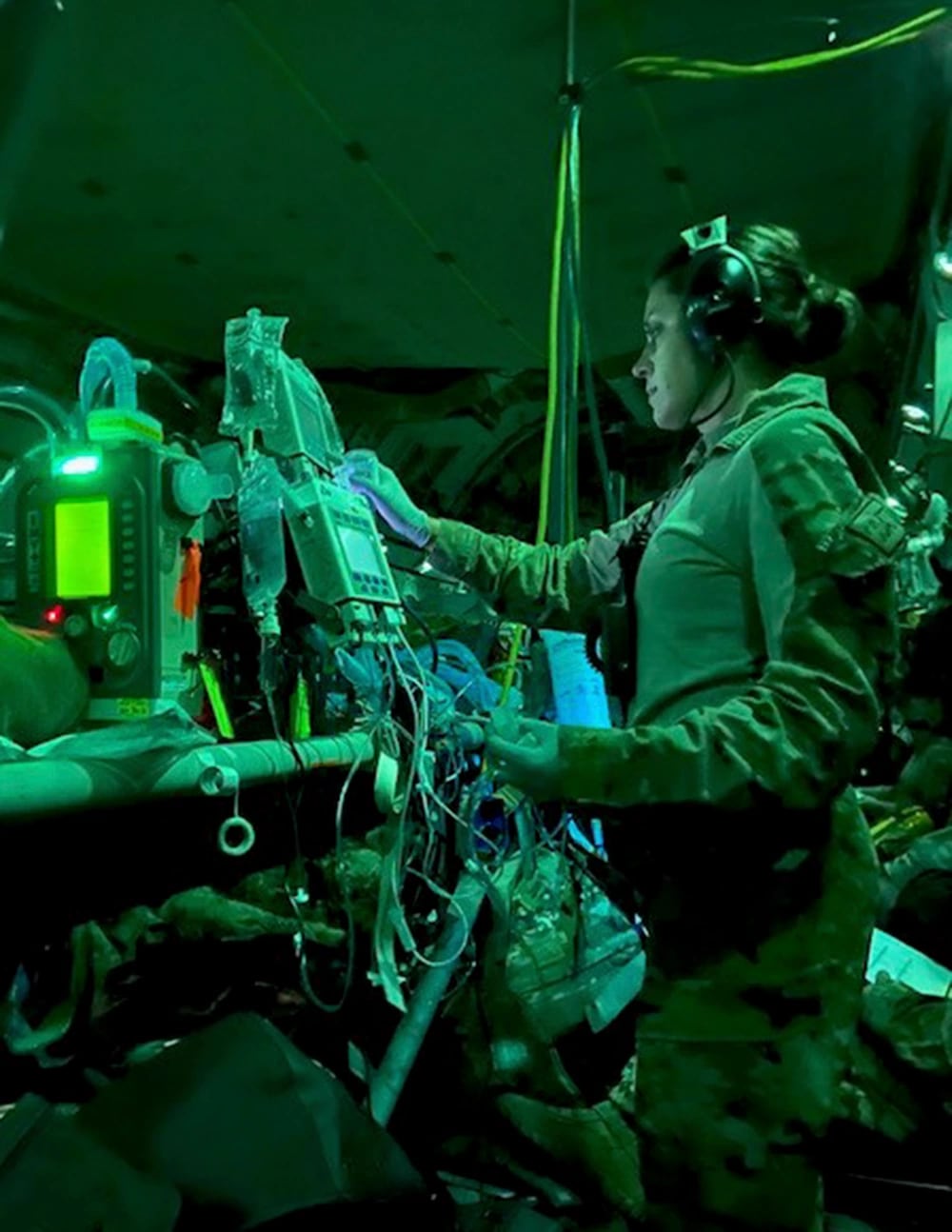

Three-person CCAT teams act as flying ICU staffs for ill and wounded troops around the world, ferrying service members from field hospitals to larger medical facilities for further treatment.

Lunning saw it as a chance to learn firsthand how those teams work in the field, with a squadron that is typically far removed from the front lines of war. And at first, it was.

She arrived at Al Udeid on July 17, 2021, and spent weeks on call but dispatched only once to help a sick Australian service member. Troops in Qatar believed the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan would last several more months.

But as town after town fell to the Taliban, the U.S. began evacuating the special immigrant visa holders, applicants and prospective applicants who had helped push for democracy there.

Then came word from Lunning’s leadership: The evacuation needed medical support.

Without knowing what lay ahead, two critical care teams devised a plan to shrink their enormous arsenal of ventilators, monitors, intravenous pumps and other equipment into a tiny footprint so that each C-17 cargo plane could bring on more passengers.

The group was also down two people, after one nurse had fallen off a Peloton bike at Al Udeid and a respiratory therapist had returned to the U.S. due to a death in the family — leaving Lunning, two doctors and one respiratory specialist to handle every ICU flight out of a country in chaos.

Kabul fell to the Taliban on Aug. 15; Lunning’s team arrived at the capital’s Hamid Karzai International Airport three days later.

“Seeing the desperation of people, leaving everything that they have behind for a chance of an opportunity in a country with freedom — nothing could have prepared me for that,” Lunning said.

But she began doing what any nurse would: making her rounds.

Armed with only a Beretta M9 pistol, Lunning would push a stretcher from the runway to the airport gates, past the throngs of Afghans clamoring to board military jets to safety, down three city blocks as the Taliban proclaimed victory from the streets, until she reached the tiny international hospital where patients in critical condition awaited.

“We had a lot of people who had flash-bangs to the face, some gunshot wounds,” she said. “We had a little girl who had some sort of disability that required her to have a [tracheotomy tube] long-term … and quite a few pregnant people that were about to give birth.”

One pregnant woman arrived with dangerously high blood pressure and in distress after watching the Taliban kill her brother, Lunning said. The woman’s husband and daughter reminded the nurse of her own family in Iowa.

“I can’t imagine being in that situation … leaving the country where we’re from, flying off to who knows where,” she said.

With a stretcher-bound patient in tow, she would return to the plane, hand them off to the medical team, and head back to the hospital to collect another. Once the crew was ready to return to Qatar, the critical care team worked to keep the patients stable until they reached the next leg of their journey.

That rhythm — fly three-and-a-half hours to Kabul, pick up a few patients, fly back to Qatar, help treat evacuees at the aid station on base, and nab a few hours of sleep — continued for more than a week. Then the bomb hit.

On Aug. 26, 2021, Lunning was heading to bed after a 20-hour mission when her phone rang: Something had exploded in Kabul. Sleep had to wait.

On the way back to Afghanistan, this time with a full medical team, Lunning learned they would be airlifting Marines.

“It was a different feeling and a sense of urgency, knowing we’re getting out our people, and our people had been killed,” she said. “Very sobering.”

The Islamic State-linked suicide bombing killed 11 Marines, a soldier and a sailor, and wounded hundreds more troops and Afghan civilians.

The crowds that had mobbed Abbey Gate before were gone, replaced by distant gunfire and sirens. Lunning retraced her route to the frantic hospital and received her first patient: a severely injured 18-month-old baby, whose mother was killed holding him when the bomb went off.

She hurried the brain-damaged infant back to the jet and returned to the hospital, again and again and again. Next was an Afghan man with severe abdominal wounds; a female Marine with a spinal cord injury; a male Marine whose heart had stopped beating.

Getting the patients to the cargo plane was just the beginning of the journey. Lunning’s critical care team needed to keep them alive on the eight-hour flight to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, the U.S. military’s premier hospital in Europe, with minimal medical equipment and staff and even less sleep.

“We’re all fighting being awake for like 40 hours,” she said. “We would hit walls from time to time. You try to help each other out, like, ‘Hey, I’ll take the vitals, you sit down for a minute or take a lap around the airplane.’”

Lunning said she polished off an entire 5-pound bag of Sour Patch Kids in a last-ditch attempt not to fall asleep.

The desperate measures worked: Three aeromedical evacuation missions moved 38 patients to higher care in less than 15 hours, recalled Capt. Kayleigh Migaleddi, another Air Force flight nurse, in a September 2022 op-ed.

Lunning’s team ferried 22 of them, including six critical care and 16 non-critical patients. All arrived alive.

When their work as a flying ICU was done, Lunning and her team left the hospital, found a Burger King, and collapsed onto the sidewalk with their sandwiches and fries — too exhausted to bother with the nearby picnic table. In all, she worked seven 20-hour missions from Aug. 18-29, 2021.

She became the first flight nurse in the Air National Guard to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross, one of the military’s highest honors for courage in aviation, on Jan. 7.

Lunning is clear-eyed about the danger she and her wingmen were in that summer. But when she sees what the Marines who survived are doing now, and thinks about the Afghans she helped, she knows she was the right person, in the right place, at the right time.

“They’re not just living. A lot of them are thriving,” she said. “Everything we did was worth it.”

See all Military Times’ 2023 Service Members of the Year honorees.

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.