The Air Force has pulled and is reviewing a basic military training course that includes videos on the history of pioneering Black and female pilots during World War II, following President Donald Trump’s order to halt diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

The unofficial Facebook page Air Force amn/nco/snco on Friday night posted an excerpt of an internal Air Force message, which said videos on the Tuskegee Airmen and Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs, had been removed from the service’s BMT course.

“In accordance with NEW DEIA [diversity, equity, inclusion and acceptance] Guidance the lesson plans listed below have been changed/alternated to meet the guidance,” the leaked internal message said, adding that the revised lessons should be used “immediately,” with the final word underlined and in bold.

An Air Force official told Air Force Times the videos themselves were not targeted for removal, but BMT classes that include diversity materials were pulled and are now under review to make sure they are in compliance with this week’s executive orders.

One of those classes, a one-day program titled “Airmindedness,” included videos on the Tuskegee Airmen and WASPs, as well as an inspirational-style recruiting video called “Breaking Barriers.”

“Historical videos were interwoven into Air Force curriculum and were not the direct focus of course removal actions,” the official said. “Additional details on curriculum updates will be provided when they’re available.”

Trump repeatedly blasted DEI programs on the campaign trail, and signed an executive order on his first day ending such initiatives, which he called illegal, discriminatory and wasteful. Trump’s newly confirmed Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth is a vocal critic of the military’s diversity programs, which he alleges have diverted its attention from fighting wars and made the military less lethal.

“The Department of the Air Force will fully execute and implement all directives outlined in the Executive Orders issued by the President, ensuring that they are carried out with utmost professionalism, efficiency and in alignment with national security objectives,” an Air Force spokesperson said in an email.

The Air Force issued a memo on Wednesday to put Trump’s executive order in practice, which ordered commands and units to pull down all public websites, social media accounts and other media for DEI offices; withdraw any DEI documents, plans or orders; and cancel training and contracts for DEI.

The service also shuttered its barrier analysis working groups, which sought to expand opportunities for members of underrepresented groups to become pilots and reach other goals in the Air Force.

The “Breaking Barriers” video that was part of the now-pulled class includes clips of aircraft — from early Wright Flyers to stealth B-2 bombers — and noteworthy airmen as it discusses the history and accomplishments of the Air Force. Later, the video displays a cockpit image of now-retired Brig. Gen. Jeannie Leavitt, the first female fighter pilot in U.S. history.

“It wasn’t that long ago, they said man couldn’t fly,” the video’s narrator said. “In 1947, we broke the sound barrier. The Tuskegee Airmen broke the color barrier. America’s women broke the gender barrier.”

“Some walls are inside your head,” the narration continued, underscoring images of civil rights activists and the Berlin Airlift. “Some walls are in the minds of others: Intolerance, ignorance, oppression.”

World War II aviation pioneers

The Air Force, like all military services, takes tremendous pride in its history, and the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group are among its most storied.

The Red Tails, as they were nicknamed, have been depicted on screen numerous times, most recently in the miniseries “Masters of the Air.” Gen. CQ Brown, then the Air Force chief of staff and now chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was named an honorary Tuskegee Airman in 2021 and awarded their signature red jacket. Additionally, the Air Force’s newest jet trainer, the T-7, was dubbed the Red Hawk, with its twin tails painted red as a tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen.

Telling the story of the Tuskegee Airmen and their achievements is all but impossible, however, without addressing the history of segregation in the armed forces and the prejudice Black troops encountered.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first and only Black airmen to fly in World War II, during a time when the U.S. military was segregated and opportunities for Black troops were limited. They were exceptionally skilled pilots, who flew distinctive red-tailed P-47 Thunderbolt and P-51 Mustang fighters over Europe, becoming known in the process as some of the best bomber escorts in the Army Air Forces. Their combat record was so successful that it helped prompt the newly formed Air Force, and eventually the entire military, to desegregate in the years following World War II.

During his first administration, President Trump promoted one of the last surviving Tuskegee Airmen, Charles McGee, who was 100 at the time, to brigadier general and honored him as a guest during the 2020 State of the Union. Hours earlier, Trump pinned a brigadier general star on McGee’s right shoulder in an Oval Office ceremony. McGee passed away nearly two years later.

“After more than 130 combat missions in World War II, [McGee] came back to a country still struggling for civil rights and went on to serve America in Korea and Vietnam,” Trump said in the 2020 speech. “General McGee, our nation salutes you.”

In a 2017 interview with Air Force Times and other reporters, McGee said bomber pilots the Tuskegees escorted gave them the nickname Red Tails, and had no idea they were Black.

“We were trained well, we were prepared for the opportunities, and although we were segregated, fortunately the record we established helped the Air Force … to say, ‘We need to integrate,’” McGee said in 2017. “We accomplished something that helped lead the country. We didn’t call it civil rights. It was American opportunity.”

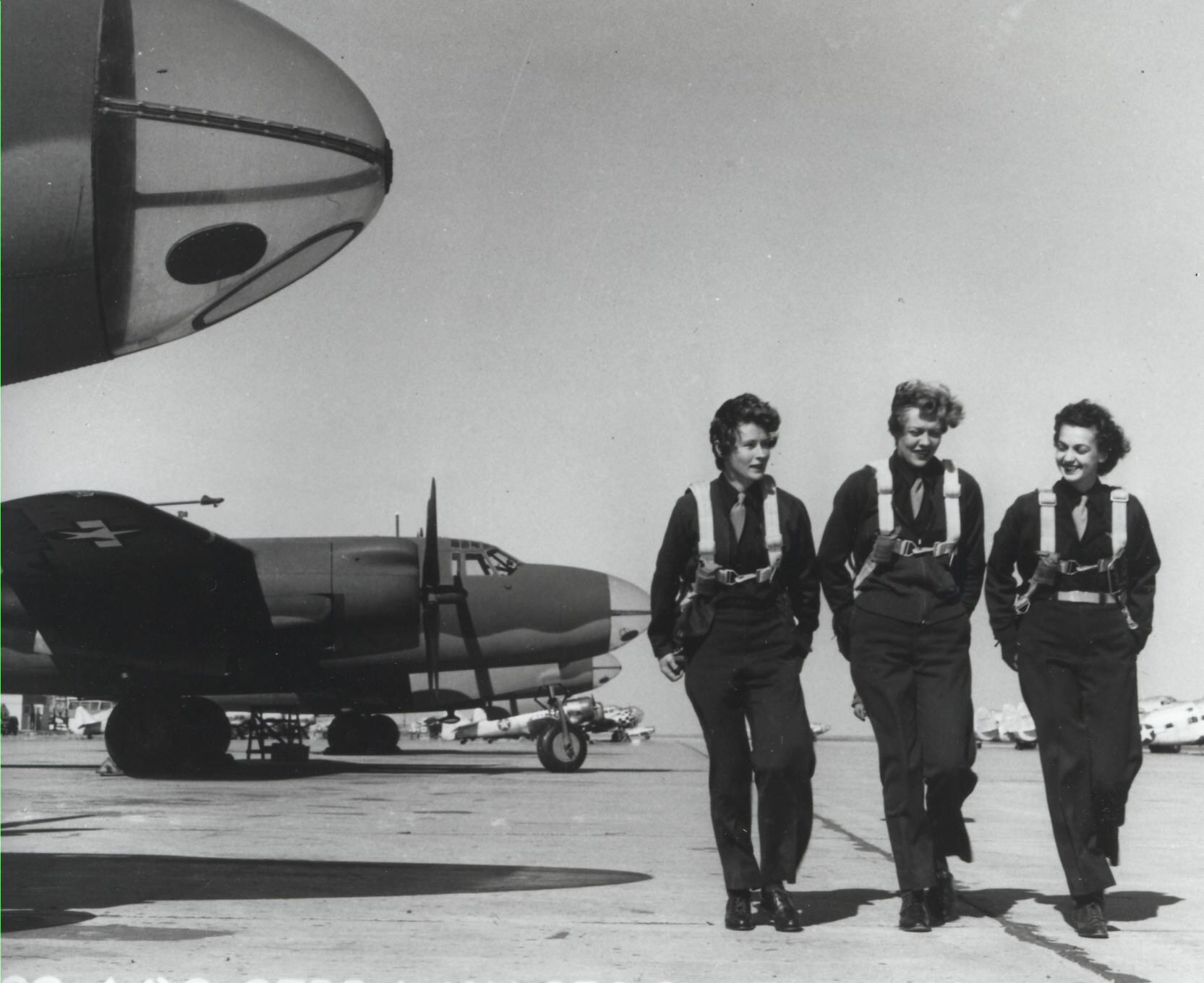

The contributions of the WASPs to World War II, meanwhile, were largely overlooked for decades, but have received growing acknowledgement and appreciation in recent years. With the vast majority of the nation’s male pilots overseas fighting the war, the Army Air Forces was stretched thin back home. So, it began to enlist the experience of hundreds of qualified female pilots.

Commanding General Hap Arnold in 1942 formed a squadron of women to ferry training aircraft from factories to bases, and set up another detachment of women to train more pilots. In 1943, those units were merged into a group called Women’s Airforce Service Pilots, which yielded the WASP nickname.

The WASPs first flew only lighter or smaller planes, but soon showed they could also handle heavier bombers and high-speed fighters. Their own training also became more advanced. More than 1,000 WASPs graduated from training during the war, and they ferried more than half of the U.S.’ combat aircraft. They also towed gunnery targets for practice, and instructed pilots how to use their instruments at the Eastern Flying Training Command, according to the Air Force Historical Support Division.

As the tide of war shifted against Nazi Germany and its once-feared Luftwaffe in 1944, Arnold and other leaders felt the crisis requiring female pilots had started to subside. A House committee that studied the WASPs concluded that “training women was a waste of resources and should be terminated,” the Air Force’s history said. The military shut down WASP training by the end of 1944.

The War Department’s director of women pilots, Jacqueline Cochran, argued in a 1945 memo to Arnold that WASPs “were as efficient and effective as the male pilots in most classes of duties, and were better than the men in some duties,” such as towing gunnery targets.

The WASPs’ records were classified and sealed for decades and largely forgotten, until the Air Force in the 1970s began opening up pilot training opportunities to women again. At that time, former WASPs began to speak up about their accomplishments, and in 1977, President Carter signed a bill granting them veteran status with select benefits.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.