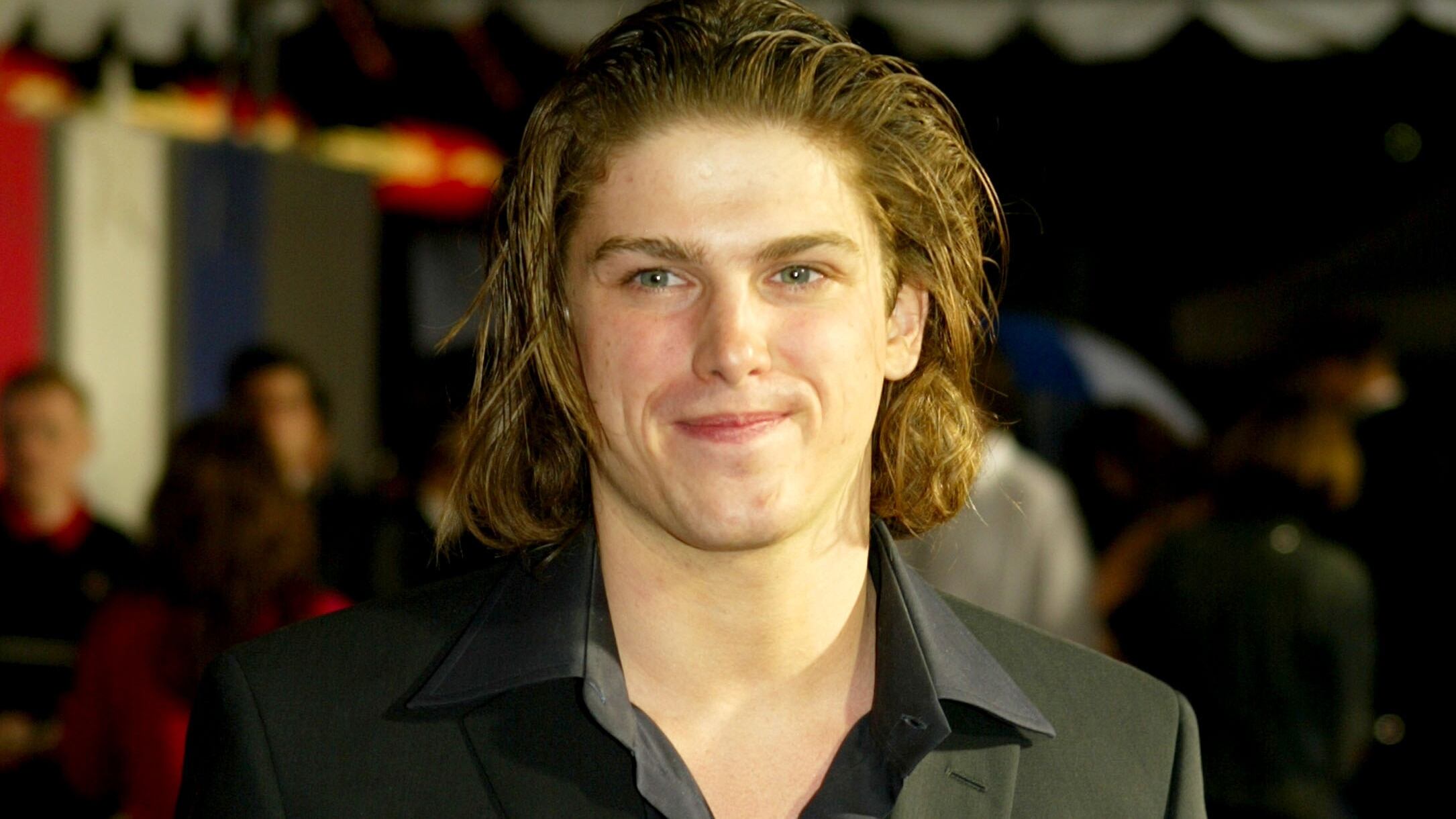

Staff Sgt. Michael Mantenuto had big plans.

The 1st Special Forces Group soldier and former college hockey athlete was probably best known for his role in the 2004 Disney movie “Miracle, ” about the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team.

After his Hollywood career stalled, he enlisted in the Army.

He had been stationed at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, since December 2013, and by 2016, he was trying to turn over a new leaf in his long-running drug and alcohol addiction, creating a peer-to-peer mental health and substance abuse support program for his fellow soldiers, under the supervision of his command.

On April 24, 2017, he was supposed to link up with a fellow soldier who was being released from in-patient treatment, to tell him about the new program, of which he’d been made noncommissioned officer-in-charge.

Early that afternoon, however, a bystander at Saltwater State Park, Washington, reported a gunshot from a parked car. Police pronounced Mantenuto, 35, dead when they arrived an hour later, according to a line-of-duty death investigation, provided to Army Times via Freedom of Information Act request.

Even before his death, his transition from a communications sergeant to a full-time peer counselor raised red flags for mental health professionals inside and outside the Army.

“Here you have an addict and a patient who’s now a subject matter expert telling the group commander that the Army program isn’t that good,” said retired Sgt. 1st Class Greg Walker, then the military liaison at a Portland, Oregon hospital where Mantenuto was being treated for drug addiction.

Walker slammed the LOD investigation into Mantenuto’s death.

“This report is a sham," Walker told Military Times. "His being allowed, as an addict, to manipulate the command both at 1st Group and at Madigan Army Hospital … was just totally contrary to the levels of expertise and experience that the medical and behavioral health people had,” Walker told Military Times in July. “They fully knew that this guy should have never been doing that.”

And, he added, they should have considered Mantenuto a risk from the time he was discharged from Cedar Hills.

He’d used heroin and cocaine on and off throughout the years, Mantenuto’s wife, Kati Vienneau, confirmed to Army Times in an Aug. 1 phone interview. And in the days before his death,he had traveled to Southern California ― without command authorization ― to attend a conference on microdosing.

Missed signs

Mantenuto had deployed multiple times to U.S. Pacific Command and once to Central Command, according to the investigation, but in the year or so before his death, had been assigned an office in 1st Group’s command wing, where he worked full-time on his war fighter recovery program, under the supervision of the group command sergeant major.

“Over the course of the 18 months that he worked on the program he expanded it to include other mental health issues, such as suicidal ideations or behaviors," the officer investigating Mantenuto’s death found.

Mantenuto had come up with the program ― stylized WAR, though its meaning evolved from World Addiction Revolution to Warrior Addiction Revolution to Warrior Action Revolution ― after being a patient himself.

In 2015, he spent a month at Cedar Hills Hospital in Portland, Oregon, where he received in-patient care for a dual diagnosis of depression and substance abuse.

That was where he met Walker, then the hospital’s military liaison, who made a point to reach out to special operations guys who came into the program.

Mantenuto had been an acolyte of the alternative therapy movement, which advocates taking tiny, “therapeutic” doses of psychedelic drugs ― not enough to get “high,” but enough to have an effect on the body’s systems, potentially relieving depression and anxiety symptoms.

Indeed, the soldier had methylenedioxy-methamphetamine ― or MDMA, the main ingredient in ecstasy ― in his system when he died, according to his death investigation.

The command’s official report found he was in good standing, with no derogatory actions at the time of his death. His behavior hadn’t changed in recent months, the investigator found.

“If anything, [Staff Sgt.] Mantenuto was focused on his future in the Special Forces Regiment,” according to the report.

Mantenuto had met with his first sergeant in the days before his suicide, hoping for guidance on getting promoted. He made an appointment to get a new official portrait taken, so that a board would have a recent photo to reference in his packet.

“[Staff Sgt.] Mantenuto didn’t display any behavior indicators leading up to April 24, 2017,” U.S. Army Special Operations Command spokesman Lt. Col. Loren Bymer told Military Times. “[Staff Sgt.] Mantenuto’s loss serves as a constant reminder for leaders at all levels to remain vigilant toward caring for one another.”

His mental health issues didn’t exist prior to his service and weren’t exacerbated by it, according to his death investigation ― though his wife told Army Times that his struggles with drug addiction long predated his enlistment ― and he had no documented traumatic brain injury or post-traumatic stress disorder that the investigating officer found.

He had been exploring the possibility that he suffered from Attention Deficit Disorder or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, the investigation found. He had completed an assessment about a week before he died, but canceled a follow-up appointment to discuss the results.

In his death investigation, USASOC redacted the pages covering risk factors and his mental health history, citing a privacy exemption.

“Behavioral health professionals employ standardized risk assessment tools to assess Service Members felt to be at-risk for potential self-harm,” Bymer said. “These assessment tools are validated through broad professional consensus and are utilized by both the Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs.”

Though Mantenuto was not officially a high risk, according to the sources cited in the investigation, the Army had known about his erratic behavior for almost as long as he’d been in uniform.

He’d been charged with property damage and resisting arrest after a night out in Wilmington, North Carolina, the Star News Online reported in July 2013. That was a couple hours’ drive from Fort Bragg, where he was a student at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, according to his enlisted record brief.

His Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor had mediated multiple fights between Mantenuto and Vienneau, the sponsor told the investigating officer.

But by late 2015, Mantenuto believed he’d found the answer: a homemade, peer-to-peer system that he would build within the Army and spread to other units.

W.A.R.

A mentor for the program, who gave a sworn statement to the investigating officer, said that while Mantenuto respected established treatment frameworks like 12-step and the various “anonymous” groups, he was setting out to make an entirely new kind of program that "stopped short of bringing other professional and non-professional services into the fold, which could support an individual as they managed addiction or behavioral health needs, or more frequently both.”

The idea was unorthodox, as U.S. Special Operations Command and its subordinate units are home to myriad mental and spiritual health programs and resources.

“Behavioral health pilot programs and initiatives are not common in Army Special Operations,” Bymer said. “U.S. Army Special Operations Command has sanctioned programs which are supported by U.S. Special Operations Command’s Preservation of the Force and Family. POTFF has a wide variety of programs and efforts to assist in health and wellness, mental and spiritual fitness for the Special Operations Community.”

RELATED

1st Group did an initial legal review of WAR in February, according to the investigation, just to cover the bases.

“It was determined there were no legal barriers to the implementation of a peer support program with the understanding the 1st SFG [redacted] would review areas which concerned risk of self and others, admission of a crime or intent to commit a crime, or any actions which may disrupt good order and discipline,” the investigator wrote.

Though it may have been above-board legally, a seasoned psychologist with a background in special operators told Military Times it was a clinical disaster waiting to happen.

“If he wasn’t following through with whatever he was supposed to be doing to help himself, he definitely shouldn’t have been in charge of anything else,” said Carrie Elk, a former clinical supervisor for Military One Source who now runs the Tampa, Florida-based Elk Institute for Psychological Health and Performance.

Mantenuto, in addition to his relapse, was not participating in out-patient treatment. At the same time, he was making presentations to units at JBLM about his new program idea, getting the blessing of both 1st Group and the head of behavioral health at Madigan Army Medical Center to get the project off the ground.

A spokesman for MAMC declined to comment, as that particular official has since retired.

“In general, as a clinician, I see all of this peer-to-peer, vet-to-vet – whether it be first responders, whether it be in the military, whether it be outside veteran groups – so much focus on peer-to-peer,” Elk said. “And please don’t get me wrong, by far, the very best first line of support ― to pick up on issues, or that someone’s struggling – 100 percent is peer-to-peer.”

But untrained and inexperienced Green Berets, for instance, can only provide so much support. A group of guys that understand your lifestyle, what you’ve been through, is great, Elk added, but not enough.

She offered an example she hears a lot, she said, in which a team guy comes to a group meeting, talks about his great experiences getting behavioral health support, and it inspires the other guys to get the help they need.

It can be a breakthrough in an insular community where discussing weakness is all but prohibited, and thoughts of reaching out can be quickly quashed by fears that a visit to a psychologist will end a career, or at least put an operator out of commission.

“I agree, that probably will break down some barriers and make that okay,” she said. “And I agree, and that’s brilliant, but guess what you have at that point? Room full of people who need help. Where’s the help? How long will it take?”

Peers are a good first step, she said, but they aren’t the only one.

“And it can be very dangerous if you project, among the peer group, that you can solve everything,” she said. “Too much of the time, the peer-to-peer stuff is where it ends. And there’s a second half to it."

WAR was in the very early stages, as far as Mantenuto’s command knew, and there had not been opportunity to make any real behavioral health referrals for its members.

“I find a lot of times that the peer-to-peer feel like they can counsel one another, but they don’t know if they miss things,” she said.

Therapy is much more involved than having a conversation with a patient, she added, and it takes training and education to do properly.

But, Walker offered, the assumption among those who knew about the program was that Madigan’s behavioral health chief had given Mantenuto his blessing with the hope that the soldier could help funnel his brothers, otherwise reluctant to seek professional help, to the hospital.

“There’s a very fine line between a peer-to-peer, brother’s keeper situation and clinical need,” Elk said, and Mantenuto was not qualified to make that determination.

‘The commander wants it’

One witness, whose name is redacted from the investigation, said he was inspired to join Mantenuto’s effort after watching a presentation he gave to the group. He never had an inkling that Mantenuto was on the edge, he said.

“After his briefing on addiction that he presented to 1st SFG, I felt an obligation to work with him to create a peer support program for personnel when they feel overwhelmed by the situations in life,” he wrote in a sworn statement included in the investigation.

He mentored Mantenuto, he wrote, meeting up several times a week to discuss WAR and to meet with other units at Fort Lewis to discuss it.

“The only thing that I thought was possible was a relapse with alcohol and even that seemed to be a far possibility,” the witness wrote. "Suicide wasn’t even on my radar.”

Another witness wrote that he had spoken to Mantenuto a week before his death, to give him a heads up about a master sergeant who was about to leave residential treatment and would be a good fit for WAR.

The investigation did not mention a May 19, 2017, meeting called by the then-group commander, which included members of the group legal team, the command sergeant major, representatives from Army behavioral health, and a couple of outside professionals ― including Walker.

He had contacted his leadership at the hospital with the heads up that one of their patients had killed himself, and they may want to do some damage control.

Walker went up to JBLM with a friend, who was then working with the Wounded Warrior Project, and the colonel asked what they might have missed with Mantenuto.

Bymer could not confirm the date of the meeting, but added that it’s not uncommon for them to happen after an incident like a suicide.

“It seemed like more of a [cover your own ass] thing,” Gary Cashman, an Army veteran who had been working at WWP when he attended the meeting, told Army Times.

The behavioral health team seemed taken aback to learn that Mantenuto had been regularly using heroin and cocaine, among other drugs, he added.

“Hey, you guys kind of knew about it, because that’s the only way he would have gotten there and someone would have paid for it,” Cashman said, surprised that the command could simultaneously know about his hospitalization while claiming they didn’t think he was a risk.

They also learned more about the soldier’s history of violence.

“His buddies had reined him in after getting in fights at the beach with his own team in Okinawa,” Cashman said, when Mantenuto had been serving in Japan.

Afterward, Walker and Cashman stuck around to talk to the command sergeant major in private. They went beyond the facts of the case, he said, to talk about special operations forces culture and how it deals with members who are struggling.

"What I commented to the sergeant major was, 'Hey, it goes against our culture, the culture we have – especially in the SOF community, ' " he recalled. “Maybe the secret bars that we have, or whatever, need to go away – and the team leaders need to learn how to be a little more soft.”

Maybe team building and bonding should involve some communications classes, he offered, or some other kind of enriching continuing education.

“Those guys should know their guys inside and out,” Cashman said. “Drinking it away isn’t a solution.”

RELATED

Unbeknownst to the command, Walker had been aware of Mantenuto months before, when a member of JBLM’s behavioral health team reached out to tell him about WAR.

There was serious concern that this soldier, a recovering addict with no professional background, could do real harm in re-imagining himself as a legitimate mental health and substance abuse counselor.

“If he relapses, that’s a bad deal, because what kind of message does that send out?” Walker said. " ‘My program is the way to go, and you can beat your demons, etc. etc.’ Now you’ve got this guy back in the Army system, and he’s relapsed."

A relapse was in play at the time of his death, his widow confirmed.

But Mantenuto’s star power seemed to have overshadowed any doubts.

"'You’re the Disney guy.’ That was the big thing,” Walker said. “He was like JBLM’s Tom Cruise. So he could get away with everything. Plus, he was an actor, so he knew how to present himself. And he was a longtime addict, so he knew how to manipulate people.”

Fallout

USASOC maintains that WAR was never an official program.

“The Warrior Action Revolution, a peer support program, was an initiative that Staff Sgt. Mantenuto presented to the group command team,” Bymer said. “The command supports initiatives which benefit soldiers, however, it was not implemented as policy.”

Still, the effects of Mantenuto’s work rippled through the Special Forces community.

Also discussed at the May 19, 2017 meeting: The far-reaching effects of Mantenuto’s death. The command had reached out to 1st Group soldiers following his suicide, to touch base with anyone who might’ve been involved with WAR.

Then, Walker recalled a group social worker telling him, they got a couple of calls from guys outside the group, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina and in Okinawa, Japan.

"The theme was common. ‘Is it true?’ and, ‘If Mike couldn’t handle it how/why should I?’ " Walker said. “That’s when they realized Mantenuto’s network had been expanded well outside JBLM proper.”

The dynamic, said Elk, the Tampa therapist, would have been a dangerous one: An addict wrestling with his own demons, hoping to redeem himself by helping others.

“When you put somebody in a leadership position, that people are to look up to, it makes it even harder to say that you’re struggling,” she said. “Because you feel like you’re letting people down. You’re leading people with problems. You’re supposed to be the one. Everyone thinks you’ve got it all together.”

Addicts tend to be consumed by shame and guilt already, she said, which could explain why his suicide came as such a surprise to his leadership and some of the people who knew him.

“You’ve got somebody who is in leadership, who is supposed to show you the way, is entrusted with responsibility,” she said. “You already have shame and guilt because you’re relapsing. How can you reach out?”

According to Walker, there is a peer still support group still meeting weekly, but it is not command sanctioned or facilitated.

“1st Special Forces Group (Airborne) is unaware to what extent, if any, the WAR program continued to meet after the death of [Staff Sgt.] Mantenuto,” Bymer told Army Times. “At this time there are no formal command sponsored peer-to-peer support groups.”

In the years since his suicide, SOF troops have been under an ever-magnifying microscope, as scandal after scandal touched the Navy SEALs, Army Green Berets and Rangers and the Marine Raiders.

Throughout the Global War on Terror, SOCOM has become a congressional sweetheart, seeing ever increasing budgets ― as well as public praise for key missions like the raid to capture Osama Bin Laden ― to apply their peerless brand of asymmetric warfare upon the world’s conflicts, with the lowest possible profile.

But murder cases, drug trafficking and general misconduct have tarnished the shine.

Last year, the Senate Armed Services Committee added a mandatory review to the National Defense Authorization Bill, requiring DoD to survey SOCOM to ensure its organizations were complying with required training on ethics and professionalism.

They were, according to the report submitted in March. But things came to a head again this summer, as SOCOM boss Army Gen. Richard Clarke ordered a second review, one delving specifically into cultural issues within the community.

RELATED

"Recent incidents have called our ethics and culture into question and threaten the trust placed in us,” he wrote in an Aug. 12 memo to the force. "I don’t know yet if we have a culture problem, I do know that we have a good order and discipline problem that must be addressed immediately.”

Clarke is not the first SOF leader to speak out. In July, the head of Naval Special Warfare Command, Rear Adm. Collin Green, released a memo with similar concerns after a string of incidents involving SEALs.

And in late 2017, both the head of Army Special Forces, Lt. Gen. Francis Beaudette, and the then-SOCOM chief, Army Gen. Tony Thomas, released their own memos addressing misconduct.

Clarke’s review is scheduled to wrap up this fall.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.