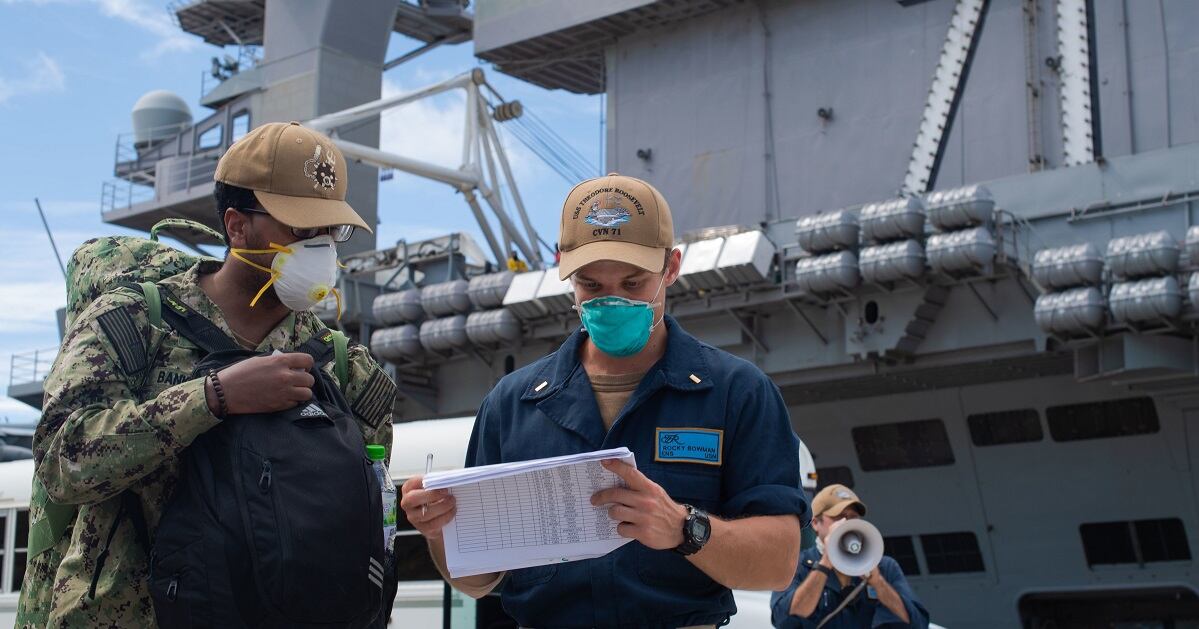

While the military has pursued vaccinating the force against COVID-19 over recent months, taking the shot has remained voluntary.

Even so, the Defense Department has made steady progress in getting the active-duty force vaccinated. Fifty-eight percent of active-duty troops had received at least one dose and 44 percent were fully vaccinated as of May 20, DoD health leaders said.

But not everyone offered the shot has taken it.

In February, reports showed at least a third of troops had declined vaccination. By March, however, acceptance rates were rising, Pentagon officials said.

Each of the services continue to provide incentives, such as fewer liberty restrictions, elimination of movement restrictions before a deployment and maskless work.

RELATED

But leaders are not allowed to punish or reprimand troops who refuse.

The voluntary COVID-19 vaccine effort stands in stark contrast to the Pentagon’s mandatory Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program, which began in 1998. Despite the questionable safety of the program, all active-duty service members were required to take the series of shots, and troops who refused often faced harsh penalties.

How the anthrax vaccination effort was handled casts a long shadow over today’s vaccination efforts in the era of coronavirus.

Keeping the COVID-19 vaccine voluntary has been supported by both recent presidential administrations and their defense secretaries, so far. But if President Joe Biden decides that fully vaccinating certain units or the entire force is a vital national security need, the vaccine could go from voluntary to mandatory with the stroke of a pen.

That’s because the COVID-19 vaccines are under an emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Only the president can override an EUA and require servicemembers to take a vaccine in that status.

Could that happen now?

A White House spokesman referred questions about military vaccinations to the Defense Department. DoD spokeswoman Lisa Lawrence pointed Military Times to a May 20 press briefing as one of the more recent responses to that question.

At the Pentagon briefing, acting Assistant Secretary of Health Affairs Dr. Terry Adirim said she could not speculate on whether it would be made mandatory, but noted that the department does mandate some licensed vaccines, as all service members know.

A vaccine is not officially licensed, however, while in EUA status.

The anthrax vaccine effort and the EUA program are directly linked.

“The shadow of anthrax comes out of Gulf War Syndrome,” said retired Marine Maj. Dale Saran a former JAG officer who represented troops who refused the vaccine.

He called the anthrax vaccination program “institutionally damaging” to the military and said the voluntary COVID vaccination program is the right approach.

“Jamming it down people’s throats didn’t help anything, either,” he said.

ANTHRAX VACCINATION PROGRAM

The Defense Department’s Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program was an effort to inoculate the entire military against the perceived threat of a bioterror attack with a weaponized version of the anthrax spore, a bacteria found in animals that can cause severe, even fatal illness in humans.

But by that time, the anthrax vaccine licensed by the FDA had already been given to some 150,000 U.S. troops during the first Gulf War, according to a 2000 Institute of Medicine publication.

The total-force vaccination effort that came after the war was seen by leadership as a way to save lives and keep units operational should they face anthrax on the battlefield.

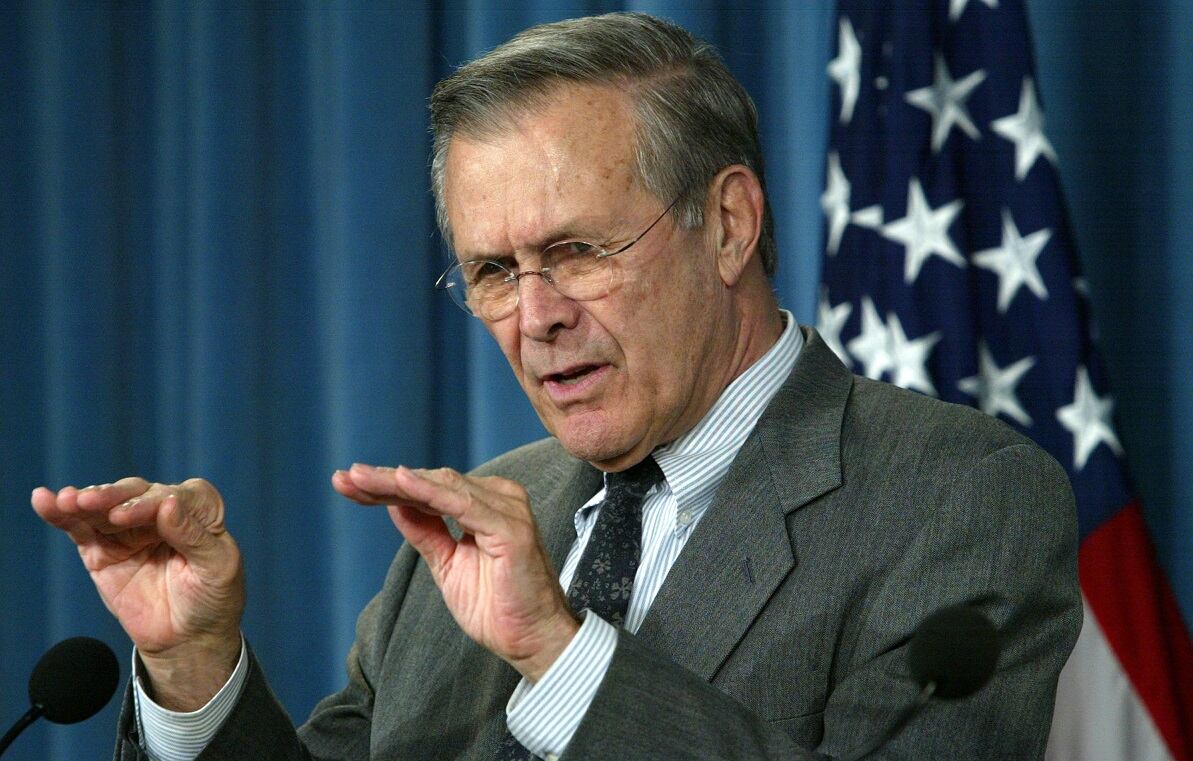

But the program was controversial from its inception. Then-Secretary of Defense William Cohen claimed the bioterror agent was an imminent threat to troops headed to the Middle East or the Korean Peninsula.

In a 1997 television appearance, Cohen held up a 5-pound bag of sugar and claimed that amount of anthrax spores would take out half the population of Washington, D.C., an assertion later debunked by government experts.

Years after the war even some military officials testified to Congress that the anthrax vaccine could not be ruled out as a cause of, or contributor to, what had become known as Gulf War Syndrome.

The vaccine itself had been plagued by problems for decades.

First approved in the early 70s, the anthrax vaccine was intended for use among people exposed to sheep and other animals who might contract the disease through skin contact.

But the military is concerned with a weaponized anthrax that can be air-delivered, causing infection. The vaccine was not tested for that kind of protection.

Though the vaccine was available, the Army sought another alternative as early as 1985, saying, “There is no vaccine in current use which will safely and effectively protect military personnel against exposure to this hazardous bacterial agent.”

The DoD used the vaccine anyway in the lead-up to the Persian Gulf War.

The sole anthrax vaccine producer, Michigan Biologic Products Institute, was cited by the FDA in 1997 for improper storage and labeling of the vaccine. Over the following years the company, then known as BioPort Corp., faced investigations, reviews and criticism over manufacturing problems.

BioPort has since become Emergent BioSolutions, the same company subcontracted to provide the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine.

The perceived Gulf War Illness connection and the problems at BioPort coincided with congressional and executive actions that, in 1998, required troops be given a choice in whether or not to take experimental drugs or procedures.

When the total-force anthrax vaccination program kicked off in 1998, defense officials didn’t see the vaccine as experimental, since it had been around and in use since 1970. But because the drug was now being used to immunize troops against inhalation anthrax, the FDA had categorized the vaccine as an “investigational new drug” in 1996.

Opponents of the defense program argued that the vaccine hadn’t been tested or approved for use against inhalation anthrax, and therefore required a new round of FDA testing and review before it could be given to troops.

In later court cases, DoD officials denied the vaccine was “investigational” and said the department had long considered it for use against inhalation anthrax, despite a lack of testing or approvals.

The actual threat of weaponized anthrax, and whether the vaccine would protect troops, was questionable.

A 2000 report by the U.S. House Committee on Government Reform noted that using a vaccine as a “mandatory, force-wide countermeasure” to weaponized anthrax was “unrealistic.”

Just prior to that report, and against the larger controversy surrounding the vaccine program, then-Capt. Thomas Rempfer and Maj. Russ Dingle were tasked by their Connecticut Air National Guard commander to research the anthrax program and provide him a report as to its safety and efficacy.

“We weren’t looking to refuse this vaccine,” Rempfer, now a retired lieutenant colonel, told Military Times. “We weren’t looking to get involved in this issue.”

But once they’d completed their research into the vaccine’s troubled history, the report they delivered called for a halt to shots and a serious reconsideration of the whole program.

Almost as soon as the program began, servicemembers began to refuse the shot. And they suffered the consequences. Later estimates showed at least 500 refused and were disciplined or kicked out of the military from 1998 to 2004.

Rempfer and Dingle refused and left the Connecticut Guard to joint the Air Force Reserve, where they resumed their careers. Others lost rank, retirement pay, spent time in the brig and were given bad conduct or dishonorable discharges.

A 2002 Government Accountability Office report on attrition in the Air Guard and Reserve related to the anthrax vaccine program showed that from 1998 to 2000, 16 percent of pilots and air crew members had transferred units, moved to inactive status or left the military as a result. Some units lost nearly a third of their members.

Federal courts brought a halt to the program in 2004 because the FDA had not licensed the vaccine, failed to follow its own rules in the vaccine’s review and allowed the DoD to use the vaccine for an “unapproved use.”

By then an estimated 1 million troops had received at least one dose of the six-shot regimen.

When the vaccine was made voluntary, Pentagon officials said about half of servicemembers declined to take the shot. In some commands, nearly three-quarters opted out.

But by 2005, the FDA made the court-directed changes and the program resumed.

That year, an investigative report by The Daily Press, a Newport News, Virginia, newspaper, revealed that over many years of testimony the Pentagon never told Congress that as many as 20,000 troops had been hospitalized after taking the shot. Shot recipients had similar complaints to their Gulf War predecessors — chronic joint pain, fatigue, arthritis symptoms, mental lapses, tingling in their extremities and sometimes multi-symptom problems.

RELATED

Defense officials disputed the number and the methods for how adverse reactions or perceived side effects were reported, saying that only 69 hospitalizations had been reported through the approved system. That was despite congressional requirements that the DoD report and track such incidents.

LETTERS THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

Dr. Matthew Nathan, the 37th surgeon general of the Navy, was a new captain in the late 1990s as the vaccination program started.

Nathan told Military Times that it’s difficult to look back without understanding the mindset regarding the threat level known at the time.

Fears that terrorists or rogue states such as Iraq or North Korea could weaponize anthrax against troops just before and after 9/11 were at a “fever pitch.”

“So, a lot of people believed that somebody being harmed by anthrax in those areas or perhaps in the states was a very real possibility,” Nathan said.

Exposure, especially inhaled anthrax, without proper protection or post-exposure methods was quite possibly fatal. Which meant mandatory vaccination was the best option, he said.

Early criticisms of the anthrax program by Congress and advocacy groups, and legal filings by servicemembers, amounted to a growing wave of pushback that seemed poised to halt the program.

But that resistance began to ebb within weeks of the 9/11 attacks when letters laced with anthrax came through the mail to the offices of news organizations and government offices, killing five and sickening 17 people, triggering public fears.

Nathan had transferred from 7th Fleet to work at the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Virginia, where he was serving during 9/11.

“When I was with 7th Fleet a lot of the questions from folks were, ‘Why do I have to take this vaccine?’” he said. “But after the letter attacks, many of those changed to, ‘When can I get the anthrax vaccine?’ "

Following the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush’s administration began considering military options against Iraqi dictator Sadaam Hussein, claiming he possessed weapons of mass destruction and warning of biological weapons he could use against military forces, including anthrax.

Intelligence before and after the 1991 Persian Gulf War showed Hussein had used chemical weapons on his own people and was developing an anthrax program.

WMD evidence did not emerge after the 2003 Iraq invasion, but the vaccination program continued.

“By the way, if Iraq or somebody else — a nation state or bad guy — had exposed hundreds or thousands of people to inhalation anthrax, we’d be having a different conversation about the vaccine,” Nathan said.

ORDERS TO TAKE AN UNLICENSED VACCINE?

Servicemembers receive a plethora of mandatory shots when they first don the uniform, as well as a variety of other immunizations depending on where they deploy.

But those vaccines, such as the measles and flu shots, have been licensed by the FDA.

In those cases, there is little to no option for troops to refuse them. While there may be legal exceptions, in most cases a refusal amounts to directly disobeying a lawful order.

During the late 1990s, however, anthrax opponents argued that because the vaccine was not fully licensed for inhalation anthrax, troops could opt out; forcing them to take it amounted to experimenting on servicemembers.

Attorney Charlie Dunlap addressed this question in a February article on the website Lawfire, which tracks cases and developments within the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The statute requires “informed consent” of servicemembers taking drugs under an emergency use authorization. But that can be waived, he wrote.

Attorney Mark Nevitt, a former Navy JAG who now represents military members, said a tension point will come if a commander on a forward deployed unit sees COVID-19 cases spike and has to make the call as to whether the unit can remain operational.

If there were an outbreak on a deployed Navy ship in active operations, the commander might decide he or she has the authority. Nevitt said he hoped the matter would be coordinated with the fleet because that is a “big, big decision that person’s making.”

PENTAGON STILL PUSHING

The idea of using experimental drugs on troops hasn’t died.

As recently as 2017 the Pentagon sought the ability to unilaterally authorize the use of unapproved drugs in battlefield scenarios. That push centered around freeze-dried plasma that hadn’t been fully vetted through the FDA licensing process but that leaders wanted available for special operations forces.

Critics slammed the proposal, saying it would open up a host of drugs and treatment that military officials could green light without checks.

Congress compromised with the DoD, writing a memo that allows the department to declare the need for emergency use permission and ask the FDA to “take actions to expedite the development of a medical product.”

Even then, the president still has the final word on making it mandatory.

Today, the anthrax vaccine is mandatory for those deploying for more than 15 consecutive days to either U.S. Central Command or the Korean Peninsula or those in an emergency response unit assigned to those areas, according to a 2015 DoD memo.

DOING IT RIGHT, FOR NOW

Rempfer and others who fought the anthrax vaccination program in court or suffered the career-ending consequences of refusing the shot roundly support the continued voluntary status of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Many saw generational shifts and perhaps history lessons learned, as contributing to the decision. Neither the White House nor the Pentagon would acknowledge, however, any link between the anthrax program history and current policy decisions.

With the internet, Saran said troops today are better able to peruse available data and make their case.

Though he’s retired and no longer part of policy discussions regarding any vaccine program, Nathan said future leaders must weigh current needs, while also being aware of the historical context.

“I think you have to evaluate any vaccine program and the impetus to mandate it based on known threats at the time to personnel and mission,” he said. “You can and should learn from retrospective analysis.”

The best way to handle hesitancy with any vaccine is education and buy-in from the troops.

“You’d always rather have somebody say, ‘I understand why I’m doing this as opposed to somebody say I don’t want to do this, I have to do this,’ " he said.

Rempfer, who spent more than 20 years dealing with the anthrax issue, sees that work paying off for a current generation of troops who are better informed and have a choice in taking the COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there is an indisputable connection. I think the military leadership is doing a great job of ensuring they’re complying with the law,” Rempfer said. “I know young service members who were specifically briefed about the law and that they had a right to prior consent.”

What the anthrax recipients and refusers endured during the early years of the program has helped frame COVID-19 and likely future efforts, he said.

“It’s been painful, but I think it’s been positive in the end,” he said.

Editor’s note: Retired Lt. Col. Tom Rempfer is the father of Army Times editor Kyle Rempfer. The son had no role in the writing or editing of this story.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.