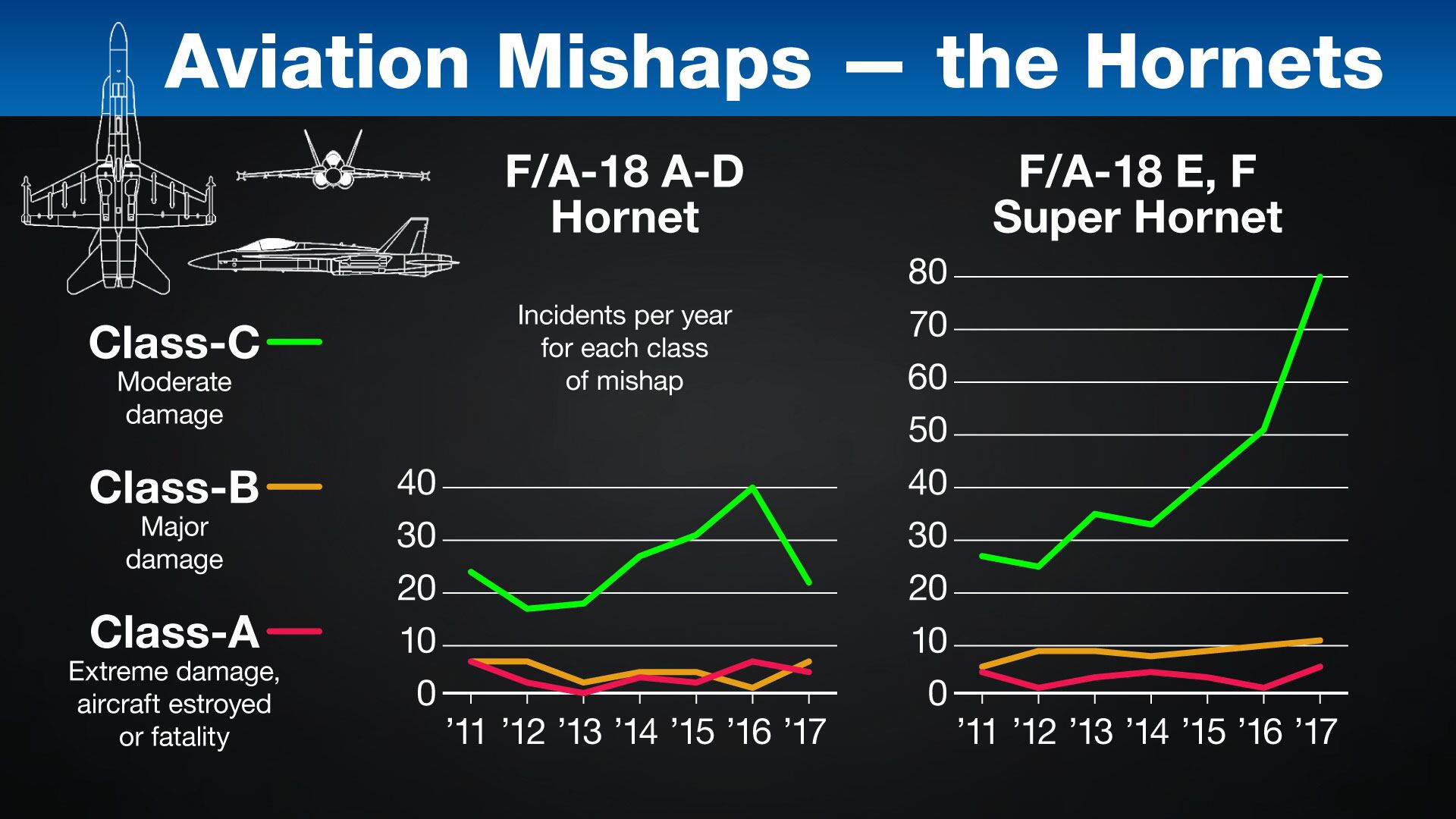

U.S. Navy aviation mishaps involving the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet have jumped 108 percent over the past five years, according to data obtained by Military Times.

From fiscal years 2013 to 2017 the number of Super Hornet accidents rose from 45 to 94 per year. Those numbers were predominantly driven by Class C mishaps, which occur when aircraft damage costs between $50,000 and $500,000 or there are lost work days due to injury.

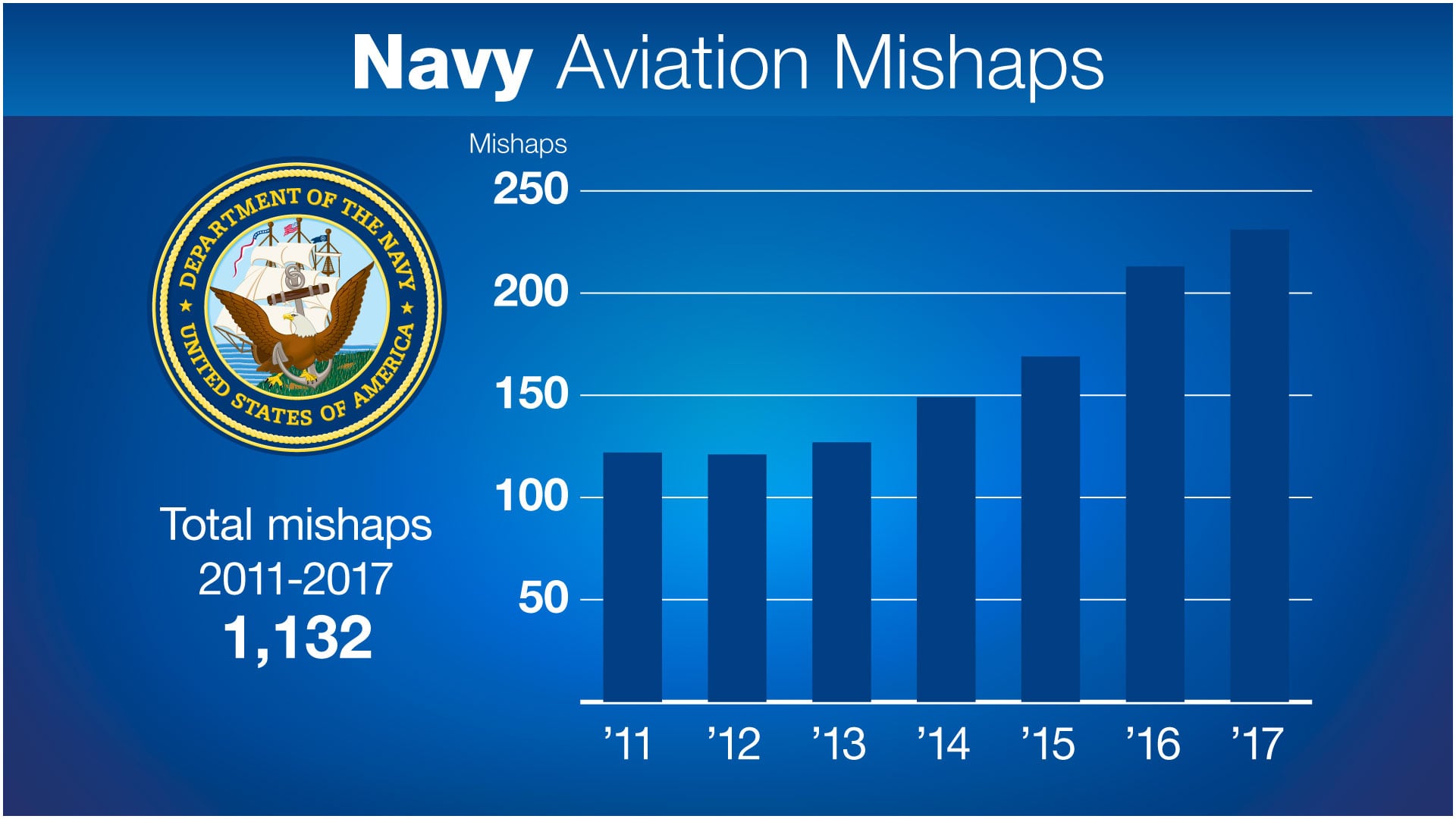

And it’s not just Super Hornets. Across the Navy’s entire aviation fleet, mishaps jumped 82 percent — mostly Class Cs — during the past five years, the biggest spike in accidents among all four services, according to mishap data provided by the Defense Department.

RELATED

The Navy is trying to understand why.

“As much as we dive into the data, it’s hard to pick the smoking gun, right?” said Capt. Dave Koss, force readiness officer for naval aviation. “So [Class] A and B mishaps remain relatively at statistical norms, but Class Cs have increased.”

The mishap data was obtained through multiple Freedom of Information requests to the Naval Safety Center.

The mishap narratives, one-liners that describe the incidents, do not reveal a common thread in the spike of Class Cs. Several Super Hornets were struck by lightning during carrier operations. There were engine fires, towing and flight deck collisions during taxi maneuvers, panels blown off aircraft by weather or the exhaust of other aircraft during shipboard operations, maintainer injuries and ground maintenance-generated damage, such as objects being closed within the Super Hornet’s canopy.

The Navy also said that as its aircraft have become more expensive, it has meant that more relatively minor incidents have met the Class C threshold. And compared to the Army and Air Force, the Navy’s smaller number of aircraft means that it does not take many additional incidents to generate a larger percentage increase in mishaps.

Common causes

Like the other services, however, the Navy’s mishap spike began after 2013, the year automatic budget cuts known as sequestration took effect.

To meet the budget caps, the Navy cut depot work and purchases of spare parts, which meant fewer available aircraft. It also let go of experienced mid-grade maintainers and their supervisors; losses that left fewer chief and senior chief petty officers on the flight line, even as the depth of experience of newer E-4s and E-5s dropped.

“With the events of sequestration and other pressures, we’ve seen a reduction in probably both of those [experienced maintainers and supervisors,]” said Capt. John Fischer, head of naval aviation safety.

RELATED

For the next five years Congress was unable to pass a budget on time. Instead it passed 17 continuing resolutions, short-term budget patches at the previous year’s funding levels. Each CR had trickle-down effects, Fischer said.

“Change is the mother of all risk. When you do not have predictability in your funding, your training, your manning, that will cause change within a particular squadron,” Fischer said. “The more you change, you can correlate that you will probably have an increased mishap rate.”

Global threats rise

Then the pace of operations increased. In 2014, the Islamic State conquered a wide swath of Iraq and Syria. China built militarized, man-made islands in the South China Sea, and Russian forces invaded the Ukrainian territory of Crimea. U.S. air power responded in each case. and for the Super Hornets that meant more flying hours on fewer ready aircraft.

Navy strike fighters had back-to-back deployments in 2015 and 2016 as the carrier air wings aboard the Roosevelt and Truman set records for the number of munitions dropped and sorties flown in airstrikes against ISIS. By 2017, Super Hornets had recorded 18,000 more flight hours than they did in 2013, according to Navy data.

“We had no idea we would be used to this extent and magnitude,” Cmdr. Jim McDonald, Truman’s weapon’s officer, said in 2016.

That pace breaks airplanes, said a Super Hornet pilot who spoke on the condition of not being identified said.

“Flying each aircraft multiple times a day, on and off an aircraft carrier (cats and traps are hard on airplanes), in the 120 degree humid Persian Gulf, tends to break things more often than just flying short flights from Lemoore or Oceana,” the pilot said.

RELATED

Making do

To meet the pace, the Navy took parts from non-deployed aircraft to make deploying units whole, which risked breaking both aircraft in the process.

“To get aircraft fully mission capable, we actually take parts out of aircraft that are in a different stage of that [deployment] cycle, and we send those parts to the air wings and squadrons that are getting ready to deploy,” Fischer said.

Or the Navy relocated entire aircraft, which further limited the time non-deployed pilots and maintainers had to train.

“We’ve had to take away from those that are not the number one priority to give to those that are forward deployed, which are the priority,” Koss said. “Although we don’t want to say that’s created a definite correlation to safety, what we can say is that it does bring in undue risk. Right? If you have to take from assets to give to forward-deployed assets, that does create undue risk.”

RELATED

The Navy commissioned a study last year to determine the cause of the rise in mishaps, with an eye toward the loss of experience that occurred after it cut mid-grade maintainers in 2013.

So far, researchers have not found a correlation between the loss of maintainer experience and Class A and B mishaps. However, when the Navy looked at the loss of experienced maintainers and Class C mishaps, “we were able to directly correlate … an increase in mishap rates as the level of years of service in supervisors went down. Not causal, but definitely a correlation,” Fischer said.

The way ahead

As it studies its younger workforce, the Navy is also taking steps to address its aged warplane fleet. It is planning to scrap scores of its older Hornets and add new Super Hornets to the inventory. The move should reduce the amount of required maintenance and allow four Navy squadrons still flying the older A-D models to transition to the Super Hornet.

And finally, six months into this fiscal year, the Pentagon has a two-year budget deal that gives the services some predictability.

“We have the best budget predictability we’ve had in a dozen years, with the two years of congressional intent,” Defense Secretary Jim Mattis told reporters.

Some of that money will go toward healing readiness woes, but it won’t happen in a flash, he said.

“It’ll take years,” Mattis said. “When you say, ‘I want an F-18 Super Hornet,’ they start building it. It won’t come to us for many, many months. But that’s the reality when you’re starting to bend metal and do more than click a mouse.”

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.