In the last three weeks, six military aviation crashes have killed 16 pilots or crew — a tragic development that has cast a spotlight on a growing crisis: Accident rates have soared over the last five years for most of the military’s manned warplanes.

Through a six-month investigation, the Military Times found that accidents involving all of the military’s manned fighter, bomber, helicopter and cargo warplanes rose nearly 40 percent from fiscal years 2013 to 2017. It’s doubled for some aircraft, like the Navy and Marine Corps’ F/A-18 Hornets and Super Hornets. At least 133 service members were killed in those fiscal year 2013-2017 mishaps, according to data obtained by Military Times.

The rise is tied, in part, to the massive congressional budget cuts of 2013. Since then, it’s been intensified by non-stop deployments of warplanes and their crews, an exodus of maintenance personnel and deep cuts to pilots’ flight-training hours.

“We are reaping the benefits — or the tragedies — that we got into back in sequestration,” said retired Air Force Gen. Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle, referring to the 2013 cuts.

The sharp increase in mishap rates is “actually a lagging indicator. By the time you’re having accidents, and the accident rates are increasing, then you’ve already gone down a path,” said Carlisle, who led Air Combat Command until 2017.

“If we stay on the current track ... there is the potential to lose lives.”

The rise in aviation mishaps has not surprised former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, who led the Pentagon in 2013 when the cuts were enforced.

“We stopped training, for months,” Hagel said. “Of course, all of that affected readiness. It’s had an impact on every part of our defense enterprise,” he said. “And that means, surely, accidents.”

Military Times has compiled and published online a database of individual reports of all Class A through Class C mishaps that have occurred since fiscal year 2011, then focused on the 5,500 aviation accidents that occurred between fiscal years 2013 and 2017.

Of those 5,500 accidents, almost 4,000 were generated by the military’s fleet of manned warplanes — all of its bombers, fighter aircraft, cargo aircraft, refuelers, helicopters and tiltrotors. In 2013, those aircraft reported 656 accidents per year. By 2017, the rate had skyrocketed to 909 per year, an increase of 39 percent.

RELATED

The accident data was obtained through multiple Freedom of Information requests to the Naval Safety Center, the Air Force Safety Center and the Army Combat Readiness Center.

Collectively, the records offer unprecedented insight into the rise of aviation mishaps during the past five years. It shows that the problems in the Navy and Marine Corps appear far more severe than those in the Air Force. And the accident rates for individual aircraft platforms vary significantly.

While hundreds of mishap reports involve life-threatening and fatal accidents, the database also reveals a steady rise in relatively minor incidents, such as a maintainer injured by falling airframe components, collisions on flight decks during taxi maneuvers or minor birdstrikes.

Across the board, much of the increase was due to a spike in those less serious mishaps, known as Class Cs, which include any incident that costs at least $50,000 and potentially up to $500,000 to fix, or leads to injuries serious enough to cause lost work days.

However, the rapid rise of minor incidents should not be dismissed, defense analysts said.

That spike “is your early warning,” said Todd Harrison, the director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“That’s your warning that there’s a problem and you need to do something before something bad happens. It‘s like a canary in a coal mine.”

Recent events have drawn new public attention to the issue. In the past three weeks, six more military aviation accidents have killed 16 pilots or crew, and destroyed six aircraft. Two Navy aviators were killed March 14 when their F/A-18F Super Hornet crashed during a training flight in Florida. A day later, seven airmen were killed when their HH-60 Pave Hawk crashed in western Iraq during a routine transit flight.

On April 3, two more crashes occurred. A Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier crashed during takeoff in Djibouti; the pilot ejected and survived. Later that day however, a Marine Corps CH-53E Super Stallion helicopter crashed during a training flight in California, killing the four crew members on board. The next day, April 4, there was another loss. An F-16 from the Air Force’s Thunderbirds crashed near Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, killing the pilot. On April 6, two soldiers were killed when their AH-64 Apache attack helicopter crashed during a training flight at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

While the causes of each crash won’t be known until command investigations are completed, Congress will get a chance to ask about the crashes next week in hearings on Capitol Hill.

On Thursday, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Joseph Dunford will testify before the House Armed Services Committee on the military’s needs going into the 2019 fiscal year. Several hours later, top aviation officers from all four branches will also testify before the tactical air and land subcommitee on their 2019 combat aviation request.

It’s not clear how blunt each service will be, as Mattis has previously warned them not to talk publicly about things like aviation readiness concerns.

“While it can be tempting during budget season to publicly highlight readiness problems, we have to remember that our adversaries watch the news, too,” Mattis directed through a memo obtained by Military Times that was sent to the service chiefs last year. “Communicating that we are broken, or not ready to fight, invites miscalculation.”

Last week, Joint Staff director Lt. Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, in a weekly press briefing at the Pentagon, rejected the idea that the recent accidents were an indicator of a larger problem.

“I would reject ‘wave’ and ‘crisis,’” McKenzie said. “Those are mishaps that occurred. We’re going to look at each one in turn. Each one is tragic. We regret each one. We’ll look at them carefully. I’m certainly not prepared to say that it’s a wave of mishaps or some form of crisis.”

Many service members, however, hope Congress won’t buy that.

“Hopefully someone in Congress will wake up and realize things are bad and getting worse,” said one active duty Air Force maintainer, who has worked on A-10s, F-16s and F-15s. “The war machine is like any other machine, and cannot run forever. After 17 years of running this machine at near capacity, the tank is approaching empty.”

RELATED

The 2013 climb

That the spike began in 2013 is significant. That was the year sequestration, the automatic budget cuts agreed to by Congress and former President Barack Obama, took effect.

“We had to cut $50 billion over 10 months that had not been planned for or budgeted for,” Hagel said.

At the time, the military’s aviation mishap rates were improving, after getting some relief due to the 2011 drawdown of forces in Iraq. Then sequestration hit. Instead of a well-funded reset, each service was mandated to execute steep budget cuts.

To absorb the cuts, each service had to make hard choices. Personnel were much easier to cut than weapons programs; which often have three- or five-year spending obligations, with expensive fines for canceling. The services’ decision at the time to cut experienced maintainers continues to impact aviation readiness today.

Critics say the services decided to cut people in order to protect aircraft platforms — like the F-35 joint strike fighter — dealing a self-inflicted wound that made things worse.

“Look at the federal budget and tell me that the money isn’t there,” the Air Force maintainer said.

“There is plenty of money there. Plenty,” the maintainer said. “It’s how they choose to spend it that needs to be analyzed and micromanaged because military leaders have failed us, in more ways than one.”

ISIS

A year after the sequester cuts, the global security landscape changed dramatically. In summer 2014, Islamic State militants conquered a wide swath of Iraq and Syria. China built militarized man-made islands in the South China Sea, and Russian forces invaded the Ukrainian territory of Crimea. U.S. air power responded in each case.

“There was a lot going on at the time,” recalled Col. Anthony Bianca, head of Marine Corps aviation plans and programs. “And then sequestration hits. Morale was low between 2013 and 2015.”

Mishaps rose 13 percent from 2013 to 2014, and kept climbing through 2017.

Notably, the number of mishaps climbed despite the fact that overall, the military flew those manned warplanes 170,000 fewer hours in 2017 than it did in 2013.

In interviews, military officials acknowledged readiness was hurt by the sequester cuts, but they cautioned against tying the rise in mishaps directly to the cuts in funding. Still, they did not have an answer for what caused the spike.

“I don’t want to speak to any correlation or causality of an increase in mishaps,” said Capt. David Koss, the Navy’s top aviation readiness officer. “But from a readiness perspective, I can say that [budget pressure] has made it much more challenging to get readiness, which does increase undue risk.”

Across all platforms, manned and unmanned, Class C mishaps rose from 808 in fiscal year 2013 to 1,055 in fiscal year 2017. That’s worrisome, defense analysts said. A Class C has the possibility of quickly becoming a Class A — the worst type of mishap — if a pilot has not had enough flying time to have it ingrained how to react. A Class A mishap means death of the pilot or crew, damage of $2 million or more, or loss of the aircraft.

Class A mishaps, across all platforms, climbed 17 percent in the same time frame, from 71 accidents per year in 2013 to 83 accidents per year in 2017. Based on a review of accident reports and open records, at least 133 service members deaths were attributed to those Class A accidents.

Stats since 2013

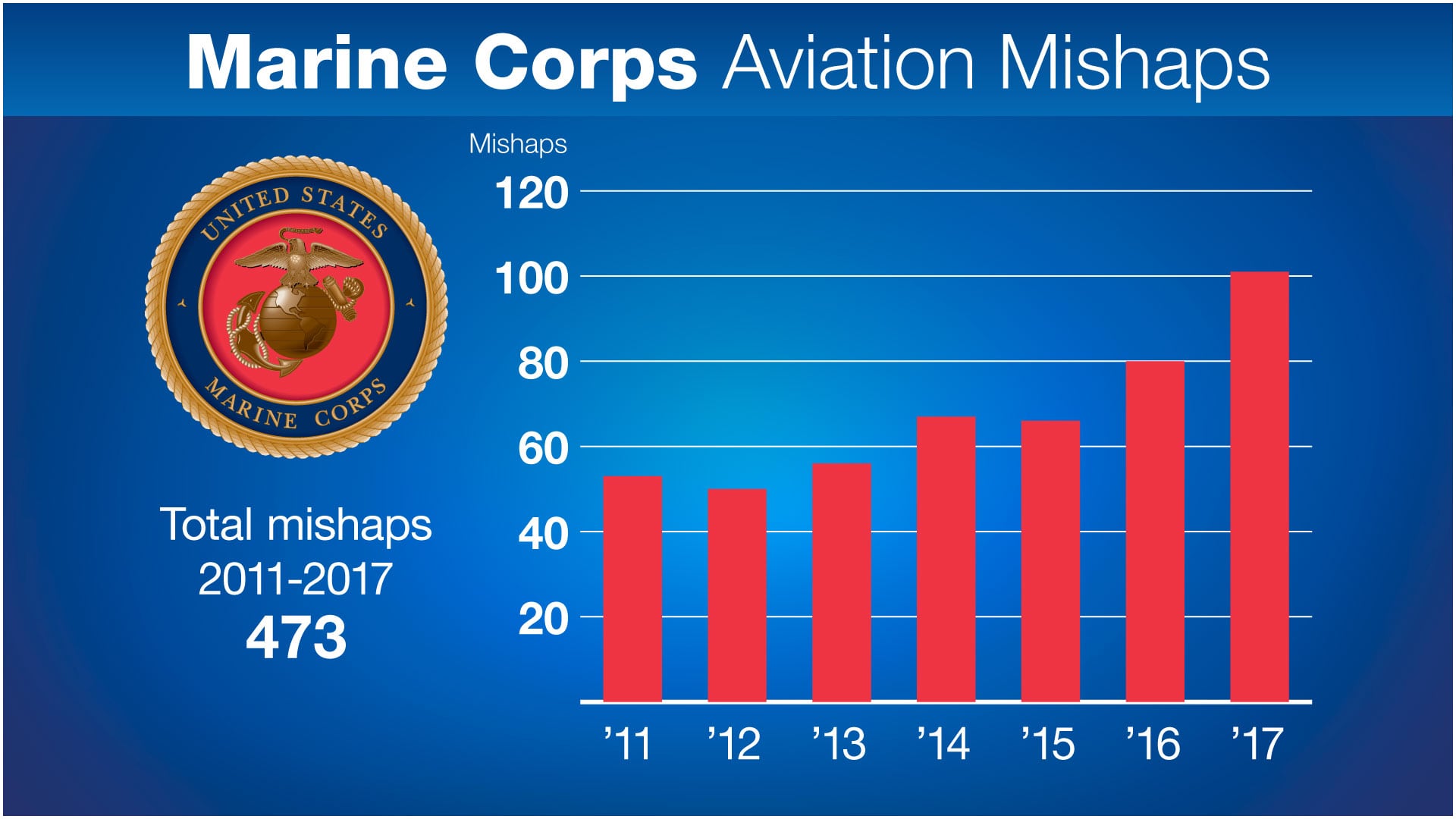

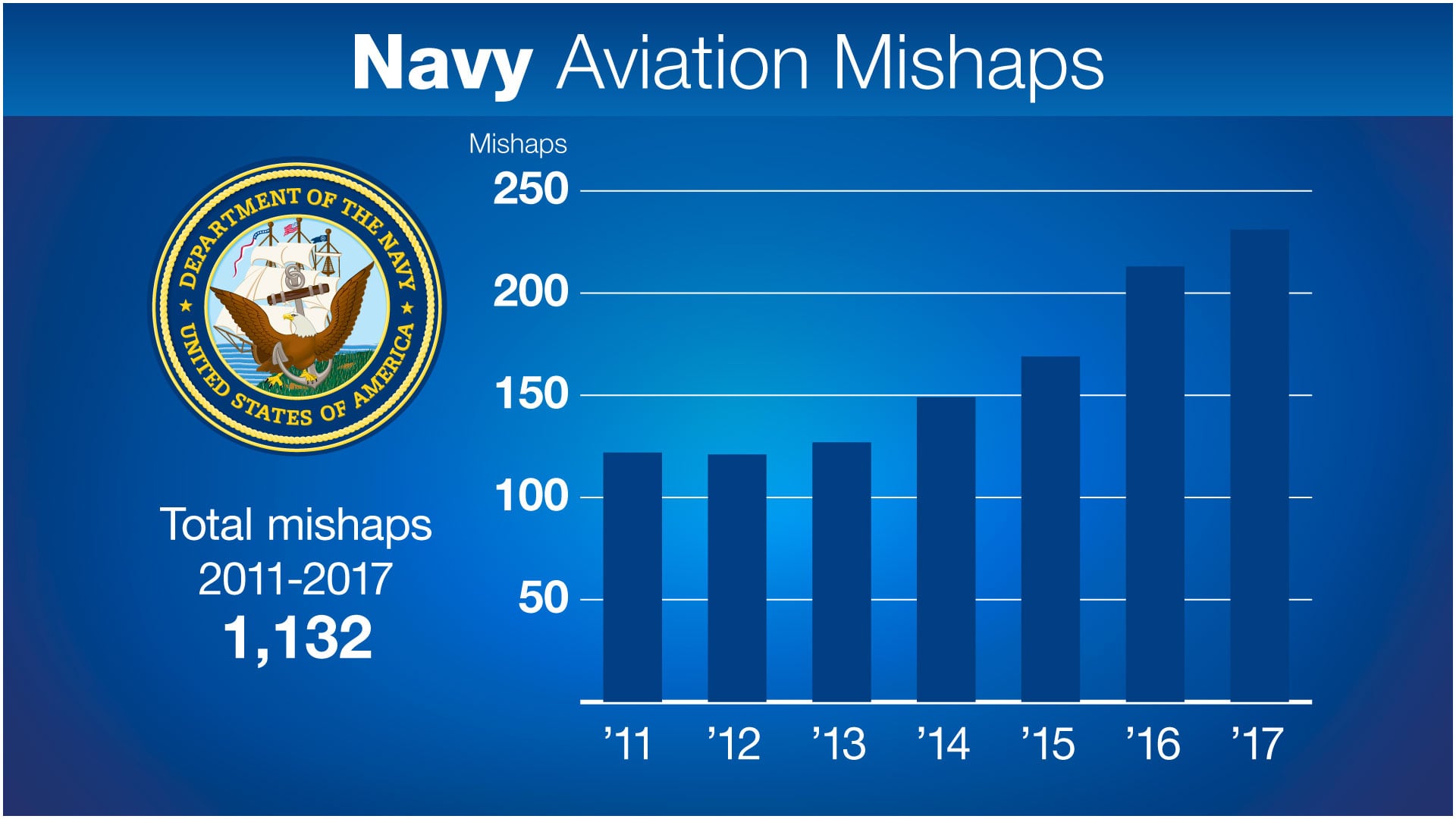

All four military services have reported a rise in mishaps over the past five years.

♦ Marine Corps mishaps jumped 80 percent, driven by Class C ground maintenance problems, such as towing incidents or tools damaging aircraft engines or canopies.

♦ Navy mishaps jumped 82 percent, driven by a 108 percent increase in incidents — mostly Class Cs — involving the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornets.

♦ Air Force mishaps rose 16 percent, driven by a rise in Class C incidents such as physical injuries in C-130H and C-17A cargo aircraft, gun-related mishaps in A-10 Warthogs, and other assorted mishaps in the F-16.

♦ Army mishaps overall rose 6 percent but declined for its most-used manned rotary aircraft.

By percentage, the mishaps hit the Navy and Marine Corps the hardest because their air fleets are about half the size of the Air Force and Army’s, so each individual incident made a bigger statistical impact. However, the spikes in Class Cs have all of the services’ attention.

“They’ll tell you it’s a pyramid,” Bianca said. “If you are having more Class Cs, then your chances of having more Class Bs or Class As go up ... I’m not sure I agree with that math, but if it’s preventable, then we need to prevent it.”

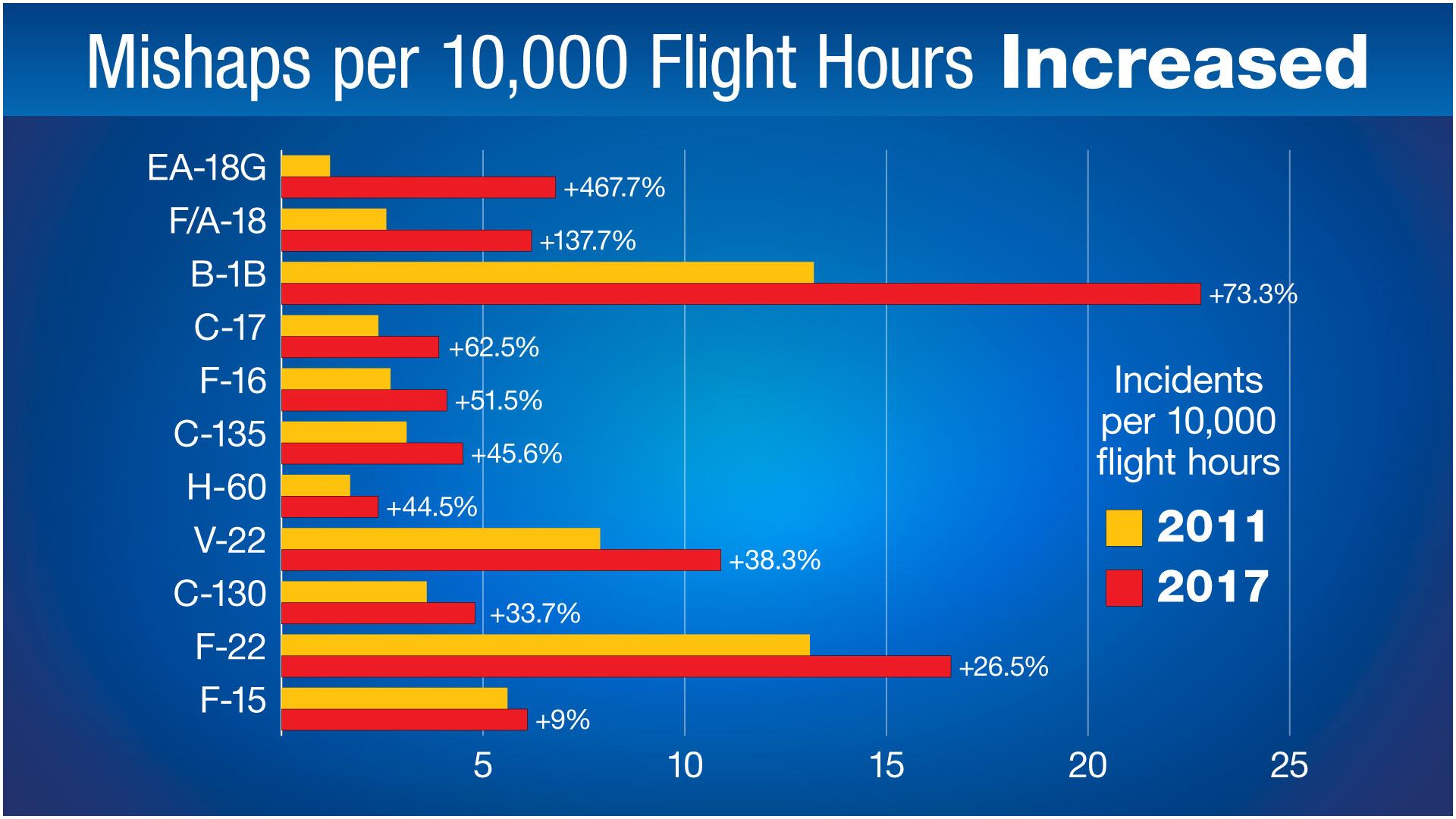

Certain airframes were hit harder than others.

For all variants of the H-60 — the Army’s Black Hawk, the Air Force’s Pave Hawk and the Navy’s Seahawk — the services flew 39,400 fewer hours in 2017 than they had in 2013. Mishaps rose from 80 to 90 in that same time frame.

The Air Force’s F-16s flew 190,000 hours in fiscal 2013, reporting 54 mishaps. The hours held steady ― F-16s recorded 189,000 flight hours in 2017 ― but mishaps hit a seven-year high in 2017, with 78 reported.

All variants of the C-130 flew 20,000 fewer hours in 2017 than they did in 2013. Mishaps rose from 80 to 99 in that same time frame.

Navy and Marine Corps F/A-18 Hornets flew 39,000 hours less in 2017 than they did in 2013. Hornet mishaps rose from 19 to 31 per year in that same time frame.

That mishaps spiked as flight hours fell isn’t surprising, analysts said. The less frequently a pilot flies or a maintainer works on an aircraft, the less current their skills are. That adds risk, said Dan Grazier, a former Marine Corps captain who is now a military fellow with the Project on Government Oversight in Washington.

“The lack of flight hours — that is the big thing I am hearing from my friends still in the service,” Grazier said. “What if they run into one of those situations where there is a minor issue with the aircraft, or where they run into an emergency situation. That is where experience comes into play.”

The sequester impact

In the months before sequestration took effect, military leadership gave lawmakers plenty of warning on the fallout.

“There’s not going to be any operations and training money left for the [non-deployed] force,” warned Gen. Martin Dempsey, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in January 2013.

That March, DoD lost about $37 billion from its base budget and received about $30 billion less in overseas contingency funding.

The services responded by reducing training and exercises, then cutting the number of experienced maintainers and pilots. However, military officials made those personnel cuts without tracking what qualifications and skill sets were walking out the door. Anyone with 15 years in service was eligible to retire with benefits, which meant the military lost upper mid-grade, highly trained personnel. The services cut more junior service members, too.

“We were cutting people. We were cutting billets and those positions that are very important as you build into the future,” Hagel said. “The consistency of that quality of people, the consistency of the training and preparation, it matters, and it will show up later.”

In the Air Force, which shed almost 1,400 maintainers to address budget shortfalls, the increased workload generated by older, more maintenance-heavy warplanes was carried out by a smaller and less experienced workforce.

“In my career field, experienced maintainers are a thing of the past,” the Air Force maintainer said. “Hardly anyone stays longer than they have to stay. Continuous training is non-existent for most maintainers.”

RELATED

The Navy is now studying what impact maintainer cuts had on the fleet. It has found that mid-grade enlisted maintainers now have an average 1.5 years less experience than their predecessors. It also found “a continued degrade in the number of supervisors, meaning chief petty officers, senior chief petty officers, as the years have gone by,” said Navy Capt. John Fischer, who heads naval aviation safety for Commander Naval Air Forces.

“We compared that to the VFA [strike fighter] community’s mishaps over the same time period, and we were able to directly correlate … an increase in mishap rates as the level of years of service in supervisors went down. Not causal, but definitely a correlation,” Fischer said.

The strongest correlation was found between lack of experience and the Class C mishaps, Fischer said.

Maintainer tracking

When the Marine Corps executed its cuts in 2013, Bianca said, leadership just looked at the occupational specialty codes to maintain “this many corporals, sergeants, staff sergeants and gunnys, and tried to balance the manpower pyramid, which by law we are required to do.” The Corps didn’t take into account whether that maintainer had obtained more senior qualifications, such as a collateral duty inspector, someone with the skills and experience to examine others’ work and ensure safety standards.

“Now we record that,” Bianca said, adding that a qualification like that can qualify a Marine for incentives.

“We lost a lot of that middle management, that salty, very experienced sergeant who can shoot the bull with you and knows exactly what is supposed to be happening, what you are supposed to be doing, and maintains the discipline. The NCO that keeps things going the right way,” Bianca said.

RELATED

The maintainer cuts are noticeable on the flight line, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Dave Goldfein told reporters last fall.

“When I started flying airplanes as a young F-16 pilot, I would meet my crew chief and a dedicated and a secondary crew chief at the plane,” he said. “We’d … walk around the airplane. I’d taxi out. I’d meet a crew that was in the runway, and they’d pull the pins and arm the weapons and give me a last-chance check. I’d take off.”

At his destination, a new crew would be waiting to perform a post-flight inspection and any needed maintenance, Goldfein said. Today, what often happens is “you taxi slow because the same single crew chief that you met has to get in the van and drive to the end of the runway to pull the pins and arm the weapons.”

“Then you sit on the runway before you take off and you wait, because that crew chief has to go jump on a C-17 with his tools to fly ahead to meet you at the other end.”

Rise in risk

By 2017, the U.S. had expanded its air campaign in Afghanistan, conducted tens of thousands of airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, increased strikes against the Islamic State and other terror groups in Africa, increased its patrols and air power in response to North Korean missile tests and Chinese militarization, and beefed up security theater packages in Europe in support of Operation Atlantic Resolve.

To meet the increased demand ― with less money and fewer people ― the services pushed readiness to the front lines. Pilots and maintainers stateside flew less, maintained less and lost proficiency. For lack of spare parts, maintenance backlogs and other issues, more and more warplanes couldn’t fly.

Fewer personnel also meant others deployed more, adding pressure on military families. For all of these reasons, many service members opted to leave the service.

“What happens then if the units aren’t adequately resourced? They’re flying less, right? Because they don’t have all the money and parts they need to keep the airplanes flying, and therefore, obviously, they’re maintaining less,” said Koss. “So if they’re flying less and they’re maintaining less, it puts more pressure on readiness.”

Class A losses

When a Class A mishap occurs, it is almost invariably the result of a chain of events, culminating with the pilot’s reaction to that chain. It’s part of the reason why the services are paying close attention to the Class C mishaps from a maintainer standpoint.

In January 2015, a fatal UH-1Y crash took the lives of Marine Corps pilot Maj. Elizabeth Kealey and co-pilot Capt. Adam Satterfield. Crash investigators found an improper installation of the filter, filter retaining ring and cover allowed oil to spill out during flight. The pilot’s incorrect assessment of the seriousness of the warning that oil pressure had dropped led to the fatal incident.

The filter was a known issue. Three waivers had been granted to allow the helicopter to keep flying until it could be addressed. But the filter’s retaining ring had been installed upside-down, which prevented a proper seal of the cover.

“It is reasonable to surmise that if the aircraft waiver was never approved and the filter assembly had been previously replaced with the correct sealant, this mishap would have never occurred,” the investigating board found.

Neither pilot had flown 17.8 hours, the Marine Corps’ monthly goal, in the 30 days prior to the crash; Kealey had flown 11.2 hours; Satterfield, 10.7, but the report did not find that to be a contributing factor in the crash.

“Aeronautical judgement does get better with increased flight time, but [Maj.] Kealey had a sufficient amount of experience to offset the small deficit in flight time over the past 30 days,” the investigation found.

The investigation did recommend that the squadron take steps to ensure “the proper supervision of flightline maintainers.”

Aircraft 205

The April 21, 2017, crash of “Aircraft 205,” a Navy F/A-18E Super Hornet was another mishap that could have been kept to a Class C but ended with the destruction of the aircraft.

On that day, VFA 137, a strike fighter squadron attached to the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson, had 10 jets launching for an exercise near the Philippines. But in final flight checks, one of the two-ships couldn’t depart — one aircraft was unflyable. The squadron provided a substitute F/A-18E, Aircraft 205.

That aircraft had just come back online after a fuel cell replacement. However, the check flight to return to operations had revealed other issues.

The communications link that provided Aircraft 205 with situational awareness of other jets worked only on deck, not in the air. The tactical air navigation system that directed 205 to the ship only worked after the Super Hornet was already overhead. The dump switch, which allows a pilot to dump fuel in an emergency, “would not electronically stay in the ‘dump’ position,” according to the Navy’s official accident report.

One of the pilots assigned to the two-ship that day was a Navy captain with more than 4,100 flight hours, 3,800 of those in the F/A-18. The other aircraft pilot was a Navy lieutenant with 320 hours in the jet.

Because 205 passed the check flight, “all involved thought [the captain’s] experience was better suited for Aircraft 205,” since it was common for long-time down jets to have minor issues. The junior officer was assigned to fly the more reliable jet.

As VFA-137’s Super Hornets flew back to the Vinson after the exercise, multiple systems on 205 failed.

The communications link failed, leaving the pilot with no situational awareness of other aircraft as the jets approached the Vinson to land. Then, indicator lights began to flash, signaling he was losing hydraulic fuel. He lost rudder control and had to idle the right engine. Troubleshooting with the Vinson’s tower ensued, but investigators found the tower representative in charge of bringing 205 in — another Navy lieutenant with 237 flying hours in the Super Hornet — “was not experienced enough to handle the emergency situation.”

Over the next 18 minutes, the pilot “became overwhelmed with flying the jet,” the investigation found. “Despite over 4,000 hours, he never had a situation where the jet was fighting him so much.”

He ultimately ejected, surviving with injuries. Aircraft 205, worth $57 million, crashed into the Celebes Sea and was a total loss.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

On Feb. 9, Congress passed a two-year budget deal. It provides $700 billion to DoD for fiscal 2018 ― now six months into the spending year ― and $716 billion for fiscal 2019. President Trump signed the spending pact into law the same day.

Service officials should take mishaps into consideration as they determine how to spend that money, said John Pendleton, director of readiness and force structure issues at the Government Accountability Office.

“Traditional readiness, at its core, is the sum of equipping, manning and training,” Pendleton said. “If you have an increase in mishaps, you likely have an issue in either training, equipping or manning, or possibly all three.”

But officials also must determine whether the increase in mishaps is really tied to money at all, Harrison said.

“What worries me is people think they just need to throw money at the problem,” he said. “What they first need to do is really research what are the factors that are affecting these mishap rates.

“It could very well be how the funding is being used, for example the type of training or maintenance to be accomplished with that funding,” Harrison said. “It could be issues with personnel, it could be issues with leadership. What this does tell you for sure is the readiness of the force to be able to operate safely is going down and this is not a good trend.”

Air Force Times senior writer Steve Losey contributed to this report.

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.