Fatal military aviation accidents have reached a six-year high, in both the number of accidents and the number of pilots and crews killed, a Military Times investigation has found.

So far, 12 fatal accidents — 11 crashes and one ground incident — in fiscal year 2018, which began Oct. 1, have claimed the lives of 35 military pilots and crew. It’s the highest number of crashes in years, and the total number of deaths so far this year ties 2016’s deadly year, when 35 aviators were also killed.

There are still four months to go in fiscal 2018.

Last week’s horrific crash of a Puerto Rico Air National Guard WC-130 brought the state of military aviation back into sharp focus. The plane’s fall from the sky was caught on video; all nine airmen aboard were killed.

Over the next 24 hours, in media briefings with reporters at the Pentagon, senior leaders downplayed the rash of accidents, calling each unique and not indicative of a trend.

“This is not a crisis. But it is a crisis for each of these families,” Pentagon Press Secretary Dana White said Thursday. “And we owe them a full investigation, and to understand what’s going on. But these are across services, and these are different individuals and different circumstances.”

The day before, Navy Secretary Richard Spencer had roughly the same response.

“We look at the five-year average, we’re not out of the norm at all,” Spencer said of the Navy’s accidents. at an unrelated media briefing just hours after the crash.

It’s that type of messaging that seeds doubt in current military pilots’ minds that Pentagon leadership is really aware of how bad the problem is — and that it’s one of the reasons they are leaving military service.

“I haven’t seen this many accidents in a long, long time,” said one C-17 instructor pilot who asked not to be identified. “Even my civilian friends are starting to notice it. That’s kind of a wake up call.”

| Fiscal Year | Total Fatal Class A Mishaps | Total Deaths |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 10 | 23 |

| 2014 | 9 | 15 |

| 2015 | 9 | 27 |

| 2016 | 9 | 35 |

| 2017 | 9 | 33 |

| 2018 | 12 | 35 |

| Totals | 58 | 168 |

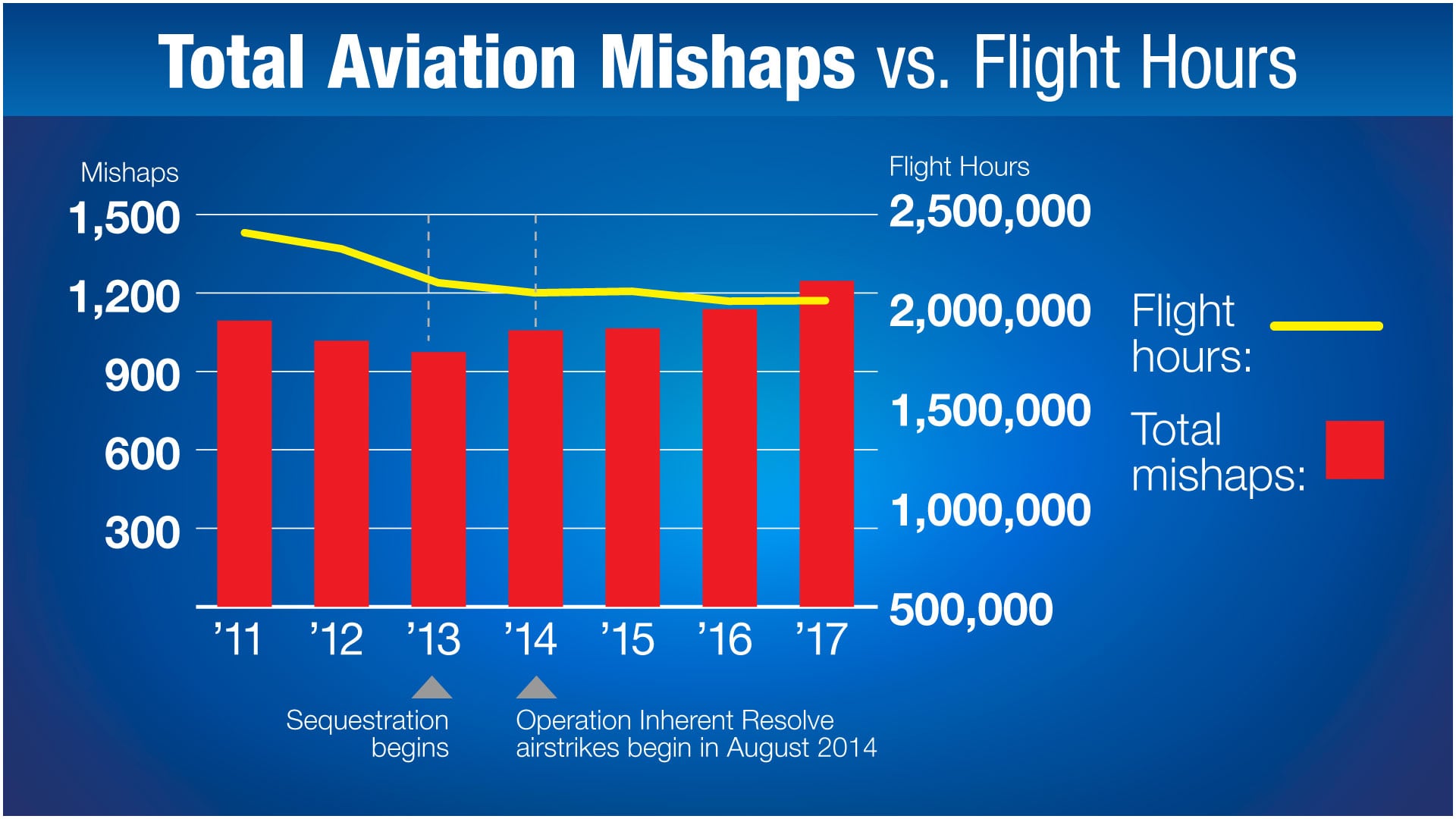

An investigation last month by Military Times found that military aviation accidents across the military’s manned bombers, fighters, cargo planes, helicopters and tiltrotor aircraft had jumped 39 percent since the automatic budget cuts of 2013.

Most of those accidents were Class Cs, the more minor incidents that either result in injury that leads to lost work days, or cost between $50,000 and $500,000 to fix.

That investigation relied on data of more than 5,500 accidents, obtained through mulitiple Freedom of Information Act requests to the services, and was limited in scope to reviewing accidents that occurred between fiscal years 2013 to 2017.

But now, statistics for 2018 are beginning to emerge. The most serious incidents, Class A mishaps — incidents that result in death to a pilot or crew, destruction of the aircraft or losses totaling more than $2 million — are on the rise, too.

“The people at the senior levels, the generals, they have their perspective: ‘This isn’t a crisis,’ ” the C-17 pilot said. “I don’t think they see the trends, or see it from the perspective from those of us who live it on the front lines.”

Zero available aircraft

What those aviators say is driving the problem: No one is getting the training they need.

First, after the 2013 budget cuts, there was no money. Now, because squadrons are smaller, pilots and crews are constantly deployed, so there’s no time to train.

For units at home, there are few available aircraft. Squadrons are sometimes down to just one available jet — and sometimes no aircraft at all.

“If you don’t train, that’s when the mistakes happen. That’s when the accidents start happening,” the C-17 pilot said.

One Navy official, who asked not to be identified, said when his squadron returned from deployment, it was gutted. The most ready aircraft were shifted to another deploying squadron. The unit would have maybe five of its full complement of 12 jets left.

But the five aircraft wouldn’t last; usually two would be pulled to a fleet replacement squadron - the units training the next generation of Marine Corps and Navy aviators, who were also short on jets. Another would likely be tasked to support advanced flying courses that lacked aircraft too.

“That leaves you two remaining aircraft, but you don’t have the parts to fix those aircraft,” the Navy official said. “Or maybe you do have one ‘up’ aircraft at the start of the day. You go to start it up, it goes down because something on it breaks.

“And now you have to wait in line, because you’re the lowest priority to get that part. So now your one ‘up’ aircraft becomes zero ‘up’ aircraft. And then you spend a whole day trying to fix that part and/or fix another jet.”

A can’t say ‘no’ culture

In previous years, when concerns were raised about the pace of operations, pilots were told, “If you don’t like it, just get out. We’ll find someone to replace you,” the C-17 pilot said.

Squadrons are so minimally manned service-wide that the earlier rebuff “has now gone away.”

They are still tasked, usually with no notice, that they are needed immediately overseas to support another critical mission. All other needs are pushed aside, no one trains, few are home long enough to reconnect with spouses and families, he said.

Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson acknowledged the strain last November in an annual “State of the Air Force” media brief.

“We’re burning out our people,” Wilson said.

When asked at the Wednesday briefing by Military Times if a “can’t say no” culture was putting aviators’ lives at risk, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson had a different take.

“These [flights] are controlled by strict regulations. We’re not violating any of those regulations. Those aircraft that we send pilots up in are fully certified to fly. The pilots that are, we send in to fly, are fully certified for the missions that they conduct.”

Congress is now questioning that, and lawmakers have cited Military Times’ in-depth “Aviation in Crisis” investigation as it looks for answers.

By service, Navy aviation accidents were up 82 percent; Marine Corps accidents up 80 percent, Air Force accidents up 16 percent and Army accidents up 6 percent.

“The service branches have been too slow to respond. These are alarming trends,” said Rep. Mike Turner, R-Ohio, in a press release Wednesday announcing that the House Armed Services’ Tactical Air and Land Subcommittee would hold a hearing on this question: What are the services doing about it?

“When we have a hearing or travel to military bases and talk to pilots, we become more and more concerned that the service branches don’t have an answer [to the rising accidents],” Turner said.

Impact on future force

The last five years have left a legacy impact on the future force. Senior aviators now moving up the ranks have hundreds of fewer flight hours than their predecessors.

“We had enough … final layer of fat that we could survive two years of this [the budget cuts],” the Navy official said. “The real problem was going to come five, six, seven years down the road, when those people who had to take the cut at the beginning of their career were transitioning into the middle part of their career — which is what we’re seeing.”

Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Robert Neller said that’s what he’s seeing, too.

“Twenty years ago, if you were a senior captain or a major, you probably had ... 1,200, 1,500 hours. People that are senior captains or majors now, they’ve probably got 800 hours,” he said.

Those less experienced leaders are now the ones responsible for training the next generation of pilots.

The C-17 instructor said he’s experiencing that first hand, as it is now his responsibility to train the next generation of pilots. Among the instructors, pressure and doubt about whether the services will be able to climb back out of this hole are leading to many of them getting out.

“I really don’t know who’s staying in [military service],” the C-17 pilot said.

RELATED

Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis has already said that there won’t be a quick fix to military aviation’s problems, despite the $700 billion budget the Pentagon has received for fiscal year 2018, and the planned $716 budget for fiscal year 2019.

“It’ll take years,” Mattis told reporters earlier this year. “When you say, ‘I want an F-18 Super Hornet,’ they start building it. It won’t come to us for many, many months.”

And it’s more than just replacing the airframes, White said Thursday.

“You can’t buy the time back,” White said. “You can’t buy the training hours back. You can’t buy the maintenance time back. You can’t do that.”

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.