Great power competition has been the primary driver of the Pentagon over the past few years, but the Defense Department doesn’t get to pick the next war.

It is more likely that the U.S. military will be drawn into another conflict against an insurgent or proxy force, than it will end up fighting naval battles in the South China Sea or halting Russian armor in the Fulda Gap.

“While you’re going to have the larger force-on-force kind of engagements, at the same time, there’s going to be action in ‘gray zone’ ... the space in between war and peace,” said retired Col. Frank Sobchak, co-author of the long-delayed Iraq War Study and a former Army Special Forces officer.

“We see this through proxies, we see militias, we see the involvement in democratic elections," Sobchak said Tuesday at a Foundation for Defense of Democracies event in Washington. "All these are things that we saw in Iraq that we learned from, that same kind of gray space action is going to occur when we have conflict with a great power.”

In January, the Iraq War Study’s two volumes were finally published online, roughly five years after the Army originally commissioned it. The findings, while at first glance appear to not be in lockstep with the Pentagon’s new focus on China and Russia, are perhaps more important than ever.

Who came out on top?

In the study’s conclusion, Sobchak and fellow co-author retired Col. Joe Rayburn wrote that "an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor” of the Iraq War.

That country looks like a victor in the Syrian civil war, as well.

Iran, which the 2018 National Defense Strategy singled out as “the most significant challenge to Middle East stability," was a covert actor throughout the Iraq War, responsible for the deaths of more than 600 U.S. troops, the Pentagon says.

The Iranian regime appears to have reemerged as a focus of Washington leaders as the fight against the Islamic State’s physical caliphate winds down.

U.S. troops will remain in the region for the time being, at places like Manbij in northern Syria. During a visit to Manbij in May, a general who formerly led U.S. Special Operations Command said Americans were “coffee breath-close” to Syrian, Russian, Hezbollah, Iranian, Turkish and Israeli forces.

The entire Syrian conflict has been a soup of proxy forces and mercenaries operating on behalf of state-level militaries. But so far, the U.S., Iranian, Russian and Syrian forces have shared the battlefield against ISIS relatively well.

That wasn’t the case during the Iraq War, and with ISIS’ territorial demise, there is the possibility that easy peace will not last, especially if, or more likely when, an ISIS insurgency begins en masse.

The common enemy is gone

The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, and its specialized Quds force, was designated a foreign terrorist organization by President Donald Trump’s administration Monday, an unprecedented move against another nation.

Iran retaliated by designating U.S. Central Command a terrorist organization and the U.S. government as a sponsor of terror.

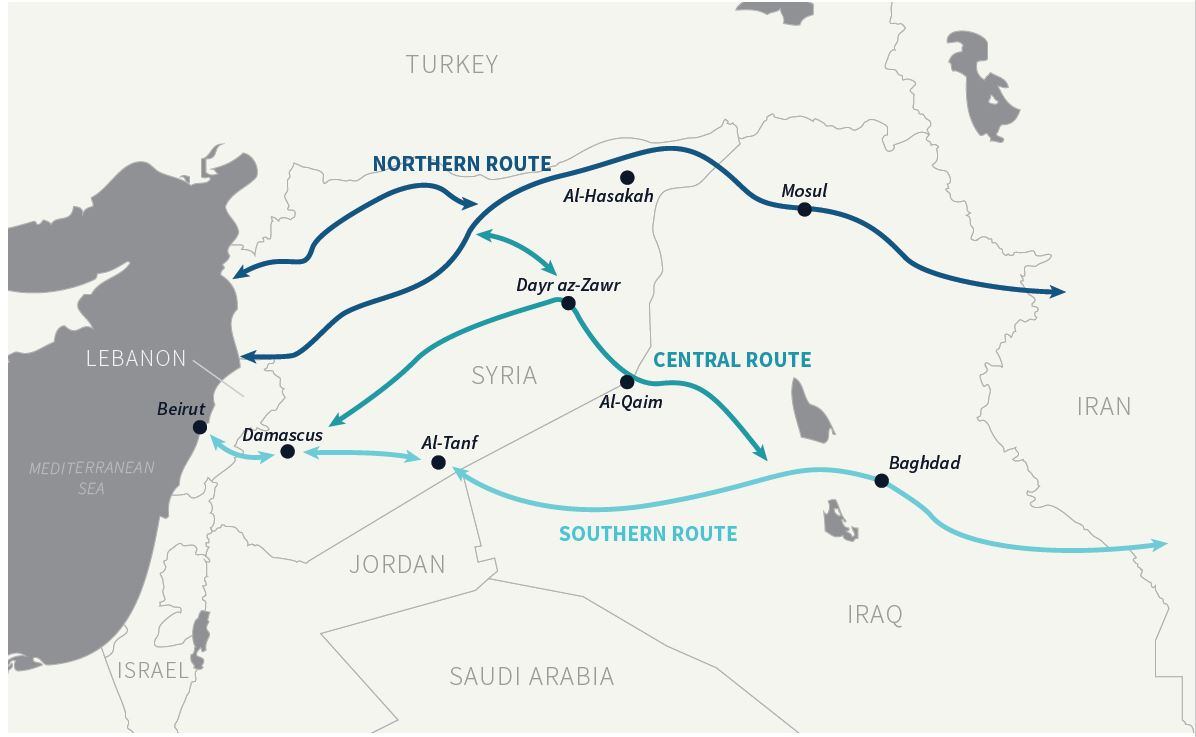

That could have implications for American outposts in the region, especially the U.S. base at Al-Tanf in southeastern Syria, which blocks one of Iran’s most direct supply lines to its Syrian regime allies and local proxy forces.

“A U.S. withdrawal from Syria could facilitate the expansion of these corridors, particularly a departure of U.S. troops from bases like Al-Tanf,” Seth Jones, a former Pentagon official and current senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in a March brief.

“The [Quds Force] is particularly active in such countries as Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria," Jones wrote. “It has provided military and non-military aid to partners, boosting their capabilities and increasing Tehran’s influence."

It’s not clear how Iran would attempt to counter the U.S. troop emplacements in Iraq and Syria, if at all. But it is important to understand the role Iranian influence played in the Iraq War.

Immediately after the invasion of Iraq, Iranian leaders feared they were next. But that evolved as a Sunni insurgency developed.

“Once they realized the U.S. was having trouble, they began slowly ... funneling in undercover operatives, buying up land, purchasing safe houses, infiltrating IRGC Quds force operatives," Sobchak said. “Over time, as they saw the United States really was not pushing back against them, it emboldened them to take further action, military action.”

One long-standing complaint by the U.S. government was that metallurgy and other forensic evidence from explosively formed penetrators — shaped charges designed to penetrate armor — had been traced back to Iran during the war.

“They took an active role in targeting American soldiers, they took an active role in aligning influence upon the Iraqi elections and were very active in directly challenging U.S. objectives,” Sobchak said.

Former President George W. Bush did not want to risk escalating a conflict with Iran, and so his administration attempted to deal with Iranian proxies within Iraq, rather than target Quds forces directly.

The Bush administration also never declared the Quds force a terror group, as they are now, nor did it designate them enemy combatants, which would have allowed them to be targeted under the rules of engagement, Sobchak said.

“Similar to the issues that are debated now, the reason why, in both 2005 and 2006, they decided not to do that was the fear of climbing the escalatory ladder with Iran,” Sobchak said.

“If we had pushed back more, I think Iran would have backed down,” he added.

Is the U.S. finally pushing back?

Because Quds force operatives were never designated enemy combatants, Iran was emboldened to continue attacking U.S. forces, said Bradley Bowman, senior director of FDD’s Center on Military and Political Power and a former national security adviser in the U.S. Senate.

The new foreign terror organization designation may have that effect, according to Bowman.

“Yes, this [designation] might increase danger, but probably the most dangerous thing is for Tehran to feel that they can continue to attack with impunity," Bowman said.

The foreign terror designation, however, is not a one-for-one comparison to the enemy combatant designations contemplated in the Iraq War days, cautioned Barbara Leaf, former deputy assistant secretary of state for Iraq and a senior Foreign Service officer.

“What does the [foreign terror] designation actually do that hasn’t been done already,” Leaf said, pointing to the sanctions already in place against the Iranian regime. “Operationally, it doesn’t have a lot of effect.”

If the U.S. military wanted to actually have an impact against Iranian meddling in Iraq during the war, it would “have had to do that on the battlefield,” Leaf said. “We failed to do that in Iraq.”

The issue, though, can still inform current policy, Bowman added.

“The historical record is clear that Iran more aggressively targeted U.S. troops when the IRGC felt that they could get away with it,” he said. "Based on this, it is perhaps reasonable to conclude that it is more dangerous to allow terrorists to act with impunity than it is to call them what they are.”

The Trump administration appears to be ratcheting up tension with Iran at a time when the Pentagon is supposedly focusing primarily on China and Russia.

But Iran is undoubtedly a major regional power, and the administration has long complained that Iranian weapons exports have been captured across the Middle East.

“We’re one [Iranian] missile away from igniting a regional conflict,” Brian Hook, special representative for Iran, told reporters in November at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in Washington.

Hook showed off a display of captured weapon systems, including ballistic missiles, guidance components and unmanned aerial vehicles, that the Trump administration says are evidence of Iran’s violation of United Nations resolutions against weapons proliferation.

“Our maximum pressure campaign will continue until the Iranian regime decides to change its destructive policies, or it can continue to watch its economy crumble,” Hook said.

The next insurgency is the next proxy war

The Iraq War Study, like the various designations contemplated against Iranian forces, is not a perfect comparison to current situations, but there are lessons learned.

Iran began seriously meddling in the Iraq War only after it devolved into an insurgency.

At the same time, U.S. troops created camps to detain local militants. These became unintended accelerators of radicalization for many detainees — the most famous of whom was future ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi.

The situation got worse in Iraq during the 2004 and 2006 time frame partially because the U.S. pursued a strategy of scaling down the troop presence, Sobchak said.

This was done because U.S. planners incorrectly thought that American forces were akin to an infection in Iraq, creating antibodies, or insurgents, just by being there, Sobchak said. At the same time, it was hoped that decreasing troops would empower the Iraqi security force apparatus to stand on its own.

Neither of these came to pass, largely due to the intense sectarian division in the country that extended to even the Iraqi government.

Portions of that equation are certainly present in Iraq and Syria today. U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces operate massive detainment camps for ISIS prisoners, and have pleaded with the international community to repatriate non-Syrian foreign fighters.

Additionally, a United Nations report in August said that ISIS still has between 20,000 and 30,000 members distributed between Syria and Iraq, posing the risk of another major insurgency.

The partner forces in Iraq and Syria appear more competent today, but the ingredients are present for a similar situation as in the surge years of the Iraq War.

And even today, Iran remains active in Iraq and Syria. Iranian-sponsored Shiite militias, for instance, were key to bringing about the defeat of ISIS.

Discussions about bringing all U.S. troops home from Syria, and not continuing stabilization funding, paint a similar picture to the 2004-2006 Iraq War decisions.

“It’s very difficult to kill something that has as much power as the extremist religious fervor of Daesh [ISIS],” Sobchak said. “To declare something over and move on, I think is very problematic.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.