Picture Marine Corps boot camp. You probably see a huge drill instructor screaming directly into the face of a determined young recruit.

Well, all that’s on hold for now.

Roughly 2,000 new recruits have passed through Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, and their experiences have looked quite different compared to those who came before them.

After an uptick in COVID-19 cases during March first forced social distancing aboard the base, there have been a lot of changes: Training companies have been at anywhere from 50 to 75-percent capacity, with open bay sleeping areas measured to an exact six feet between every bunk; trainees and cadre are keeping their distance both inside facilities as well as outside, and wearing masks wherever they can’t stay apart; and a two-week quarantine period prior to the start of practical training has turned into something of an extended study and acclimation session.

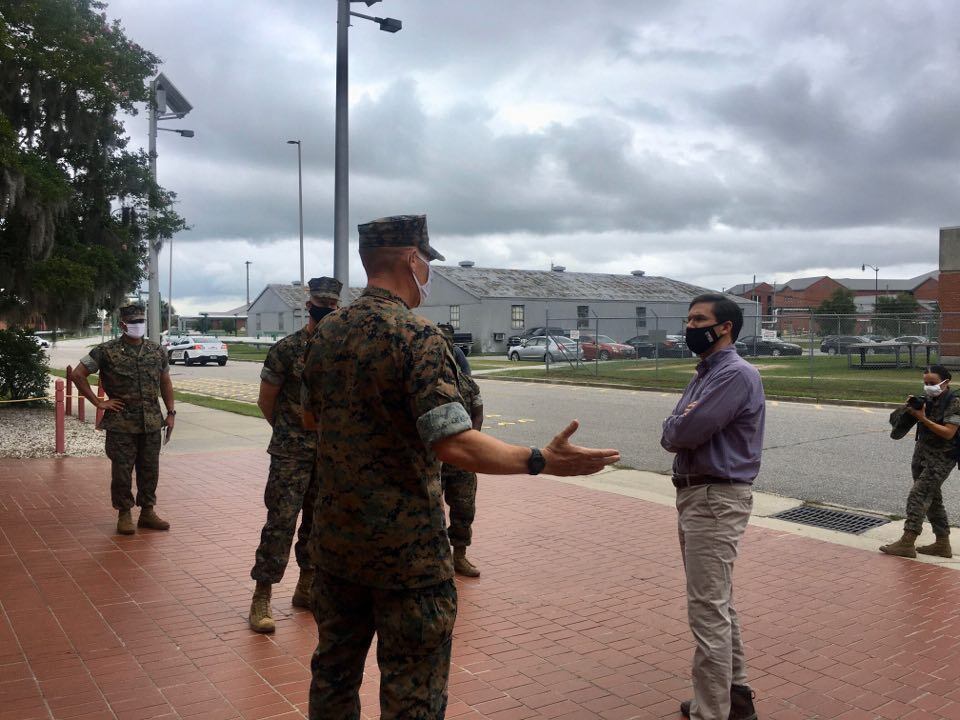

“They said they’re coming out of their restricted period more confident and more at ease,” Defense Secretary Mark Esper told reporters traveling with him to Parris Island on Wednesday. “They had more time to study and focus and are just coming in a little bit smarter.”

It started with an ad hoc tent city, sealed off white structures with shower trailers and outdoor handwashing stations, not unlike those you’d see at a pre-deployment training center.

Dubbed the “expeditionary staging area,” 900 recruits called it home for their first two weeks of boot camp, before the Citadel — a nearby military college that had sent all of its students home for the semester — opened up its housing as a more comfortable option.

During that initial period, recruits are living in dorm rooms with two to four each, studying written and online materials that include customs and courtesies, history, rank structure and other basics.

That isolation time is building more thoughtful recruits, officials said, as they’ve been able to focus, rest up and study before the onslaught of combat training.

“The two weeks of restrictied movement on the front end … its given those men and women that are new to this ― they’re singularly focused on two weeks of mental and emotional preparation for what you guys are seeing here today,” Maj. Gen. James Glynn, the base commander, told reporters Wednesday.

They are regularly screened for fevers and other symptoms during the isolation, then tested for COVID-19 at the end. If they come back positive, it’s another two weeks in isolation, along with their roommates and anyone else they came in contact with.

The rate of positives has been anywhere from one to three per cohort of 200 or 300 recruits, as the numbers who ship to boot camp have fluctuated throughout the spring.

“Really, the only big difference is the amount of recruits that I have in my series, because I’m used to having double what I have right now,” Staff Sgt. Katheryn Hunter, a Parris Island senior drill instructor, told reporters.

RELATED

Though the social distancing and masks haven’t made much of a difference in the training, she said, there has been a noticeable decrease in another issue ― other communicable disease.

“The crud,” the stuffy-nose-wet-cough cold that routinely makes its way around every type of military unit from a deploying ship to a special operations team in field training, hasn’t had nearly as much of an impact on boot camp these past few months as it usually does. The same goes for other notorious basic training illnesses, like strep throat and the flu.

“We’ve seen our illness rate come down precipitously,” Glynn said, meaning more recruits than usual are getting through training without having to take time out for sick call.

Both Hunter and Glynn attributed that not only to the spaced-out traning and face coverings, but the increased cleaning protocols in common areas.

“We need to keep things going through, but I think the future of how infrastructure is built — how many people can you fit in a confined space and how do you build buildings to support that kind of spacing in the future?” Glynn said, pondering a future where training units could be more physically dispersed to prevent spread of illness in general.

And despite the pandemic, officials said, there hasn’t been an uptick in wash-outs or issues with failure-to-adapt, despite the compounded stress of the most demanding 13 weeks of most of these recruits’ lives, while fears about contracting an illness ― or maybe worse, being away from family at risk ― abound.

“All the recruits here, since they went into two-week quarantine, being here they’ve gotten their mind right and they know that this is where they want to be,” Hunter said.

The way forward

The end of boot camp’s 13-week slog has traditionally included family coming to visit for graduation, then 10 days of freedom to go back home and decompress.

But in the time of COVID-19, that kind of travel has been restricted, so instead, families are staying home and new Marines are staying on base with a few days to prepare for the next step.

“With only three or four days of light duty or no duty, as compared to 10 days of going home, they’re showing up at the next phase of training in much better shape, they haven’t been out drinking or causing problems, they’re more focused,” Esper said.

That might be a permanent change, Esper said, per his conversation Wednesday with Glynn.

“So they’re starting to think, maybe we won’t go back to 10 days off,” Esper said. “He said, a lot of kids join because they’re trying to escape home, and you’re putting them back in an environment that they don’t want to be in, or around bad influences.”

Each service is largely responsible for its own initial entry training practices, but Esper said he’s collecting lessons learned from all four corners that might be useful going forward.

“How are they tweaking the machine beyond coronavirus?” he said.

One new development, which is starting to roll out, is antibody testing.

With more than 6,000 service members diagnosed, and estimates that between 50 and 70 percent of the total total number infections could be asymptomatic and undiagnosed, the military will be a key population for studying how coronavirus spreads and how it affects people, particularly the more young and healthy.

Researchers from the Defense Health Agency are already tracking asymptomatic cases and, on a volunteer basis, studying troops who’ve been affected.

“We may want to ask you to stick your arm out and donate blood,” Joint Chiefs Chairman Army Gen. Mark Milley said Thursday during a senior leader town hall streamed live from the Pentagon, as plasma from survivors could be used in therapy for those experiencing complications.

Testing has already begun for high-priority communities, like counter-terror units and Air Force or Navy nuclear deterrence commands, Milley said.

And the donations could be sent to the most at-risk military populations.

“If we can produce this and give you units of blood to take aboard ships and deploy, would you want that?” Esper told reporters on Wednesday, recalling conversations with Navy officials. "They’re all [saying], ‘Yes, that would be helpful.’ "

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.