Now that the active-duty military has completed its mandated stand-downs to discuss domestic extremism, the Pentagon is lining up the next moves.

After meeting with the service secretaries, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin is standing up a domestic extremism working group, according to a memo released Friday.

“I don’t want to speak for them, but it was clear to the secretary that they took it seriously, the stand-down,” Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said of Austin’s meeting, “that they believed their people took it seriously across the force, that the listening sessions that the secretary asked for [were] particularly fruitful and valuable.”

The Countering Extremism Working Group’s first order of business is to come up with an actionable definition of extremism, which will update a current Defense Department instruction that allows for membership in known extremist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan or Proud Boys, as long as one isn’t an “active participant” in a group’s activities.

“One consistent thing that he did hear is that the force wants better guidance,” Kirby added.

Whether that includes a list of groups as a reference, the Pentagon is making sure to emphasize that unaffiliated, lone-wolf types are also on the radar.

“It’s not just about group membership ... it’s about the ideology and the conduct that that ideology inspires,” Kirby said. “Some of this radicalization occurs on an individual level.”

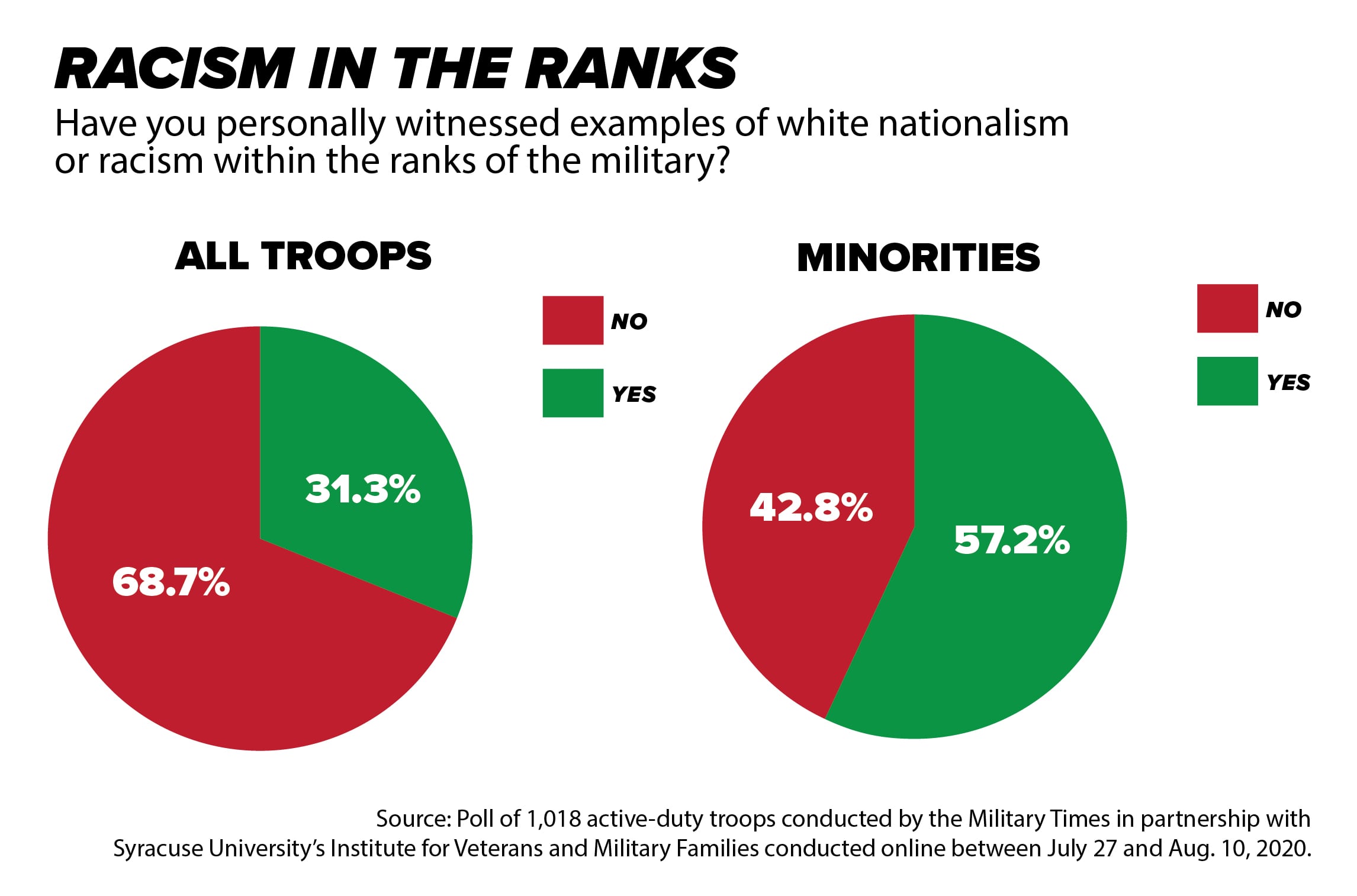

Thirty-six percent of troops who responded to a 2020 Military Times poll reported having witnessed racist or white supremacist ideology while serving.

RELATED

During a March hearing on domestic extremism in the military, Republican members of the House Armed Services Committee expressed concerns that efforts to root out extremism would unfairly target conservative, religious troops.

The Pentagon’s working understanding of extremist ideology centers more around the violence against or subjugation of groups based on their “personal backgrounds,” Kirby said, rather than religious beliefs.

“That wasn’t a concern that the secretary heard today at all,” he added.

The working group will also update transition checklists the services run through when discharging troops, adding training that focuses on extremist groups’ coordinated targeting of military veterans in their recruiting efforts.

On the other end of a career, the group will help tighten up screening procedures for recruits seeking to join the military, including a standardized questionnaire “to solicit specific information about current or previous extremist behavior.”

And finally, the group will undertake a study of extremism in the force, in an attempt to gain “greater fidelity on the scope of the problem.”

Bishop Garrison, DoD’s senior adviser on human capital and diversity, equity and inclusion will lead the group, which will bring its recommendations for mid- and long-term efforts to Austin in July.

The group will also take a look at military policy and legal frameworks for counter extremism, as well as oversight of existing insider threat programs, screening capabilities and education/training to counter extremism.

RELATED

One of the biggest sticking points for the Pentagon, and one of the most asked questions, since the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection ― which law enforcement officials have said comprised many military veterans and at least some current reservists ― has been whether DoD has any data on the incidence of extremism in its ranks.

In short, it doesn’t. In response to a request for information, the Pentagon told Congress in 2020 that it had discharged 21 troops in the previous five years for extremist activity.

Discharges are a common outcome for service members investigated for extremist activity or affiliation. This is primarily because any criminal charges are generally levied by the Justice Department, which handles many of the military’s extremism cases, leaving it up to the military to discharge them so they can be sentenced federally.

At the same time, involuntary discharges are a common way of handling troops who are a threat to good order and discipline but aren’t necessarily criminal.

“Not all, but in many, people did express that they understand this is a problem, that some of them have experienced personally ... quite a few personal anecdotes about experiencing it, and I think that was reflected across the force,” Kirby said of feedback from the force-wide stand-downs.

Though efforts picked up pace early this year, the incidence of extremism in the military has been gaining more and more attention in recent years, most notably with requests for information from Congress.

Last June, a report to the armed services committees suggested several fixes, only one of which the Pentagon did not immediately adopt: creating a separation code that would immediately identify a service member on their discharge paperwork.

The report says DoD will look into it, but the Pentagon’s personnel and readiness directorate could not confirm in March whether it was still under consideration.

A more thorough data set of extremism would involve not only culling judicial and non-judicial punishments related to extremist behavior, but also force-wide surveys for collecting anecdotes about experiences with extremism, not dissimilar to the way the Pentagon surveys its work force on sexual assault and harassment.

Austin, for his part, has said he believes “99.9 percent” of troops are serving with honor and dignity, though that is an “colloquialism,” Kirby told Military Times on Friday.

“Even though the number’s small, it can have a corrosive, outsized effect, and that’s the point he’s trying to make,” Kirby said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.