Since Queen Victoria instituted the Victoria Cross in 1856, five American-born men have received Britain’s highest military award for valor.

The first, William Henry Harrison Seeley from Topsham, Maine, was driven by a family squabble to go to sea when he was 22 years old. After deserting a merchant ship in Boston, he enlisted in the Royal Navy and served aboard the warship Impérieuse on the China Station during the Taiping Rebellion.

In 1862, he transferred to the frigate Euryalus, on which he participated in a multinational punitive expedition to take out shore batteries that a Japanese daimyo, Mori Takachika, was using to bombard any European vessels that sailed through the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshu and Kyushu.

Reconnoitering from Euryalus on Sept. 5, 1864, Seeley pinpointed a stockade and while wounded by grapeshot, returned to give a full report to 1st Lt. Frederick Edwards. Afterward, Seeley was taking part in an assault on Mori’s batteries when his captain, John Hobhouse Inglis Alexander, was badly wounded in the ankle, at which point Seeley carried him a quarter mile on his back to reach safety.

On Sept. 22, 1865, Seeley was awarded the Victoria Cross for his heroism at Shimonoseki. Seeley returned to Massachusetts, where he died on Oct. 1, 1914.

By the time of Seeley’s death, there was a new, rapidly expanding war in Europe, which included the British Empire and would soon involve the United States. The war would set the stage for four more Americans to earn Britain’s highest honor while passing themselves off as Canadians.

George Harry Mullin was born in Portland, Oregon, on Aug. 15, 1891. When he was 2 years old, Mullin’s parents resettled north of the U.S.-Canada border in present-day Saskatchewan.

Given the circumstances, Mullin had little trouble enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in December 1914. He was attached to the scout and sniper section of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

Shipped to France, Mullin managed to survive the hazards and miseries of the trenches for two years, during which he was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery during the capture of Vimy Ridge in April 1917.

In July 1917, the British launched a new offensive centered around Passchendaele, which, like previous attempts, degenerated into a succession of struggles against one well-defended German objective after another.

Within that context, on Oct. 30, Mullin had his moment, as quoted in the Jan. 11, 1918, issue of the London Gazette:

“When single-handed he captured a commanding ‘Pill-box,’ which had withstood the heavy bombardment and was causing heavy casualties to our forces and holding up the attack. He rushed into a sniper’s post in front, destroyed the garrison with bombs, and, crawling on to the top of the ‘Pill-box,’ he shot the two machine-gunners with his revolver. Sgt. Mullin then rushed to another entrance and compelled the garrison of ten to surrender.

“His gallantry and fearlessness were witnessed by many, and although rapid fire was directed upon him, and his clothes riddled with bullets he never faltered in his purpose and he not only helped to save the situation, but also indirectly saved many lives.”

Mullin left the military as a lieutenant and returned to Moosomin, where he married and had four children. In 1934, he served as sergeant at arms at the Saskatchewan Legislature. During World War II, he served as a captain in the Veterans’ Guard.

Retiring as a major, he died in Regina on April 5, 1963, and is buried in Moosomin. His VC is on display at the Museum of the Regiments in Calgary, Alberta.

There would be three more Americans serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force whose extraordinary actions earned them a Victoria Cross, all in 1918.

Raphael Louis Zengel was born in Faribault, Minnesota, on Nov. 11, 1894, but shortly thereafter his mother moved to a homestead in Canada.

In 1915, Zengel enlisted in the 5th Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 1st Canadian Division, Canadian Expeditionary Force.

During a trench raid near Passchendaele, on Nov. 11, 1917, his platoon leader and platoon sergeant were disabled, but he took charge to accomplish the mission, for which he was awarded the Military Medal in March 1918.

Five months later, as his unit was advancing east of Warvillers on Aug. 9, 1918, Zengel noticed a gap in his formation where a German machine nest threatened his battalion with flanking fire. Rushing across 200 yards of open field, he killed two enemy soldiers and scattered the rest, after which he led and inspired his battalion for the rest of the day’s advance.

For this, King George V awarded him the VC at Buckingham Palace on Dec. 13, 1918.

Serving in the Calgary Fire Department until 1927 and on the home front in World War II, Zengel retired from his second conflict as a sergeant major. Zengel died on Feb. 27, 1977, and is buried in Alberta.

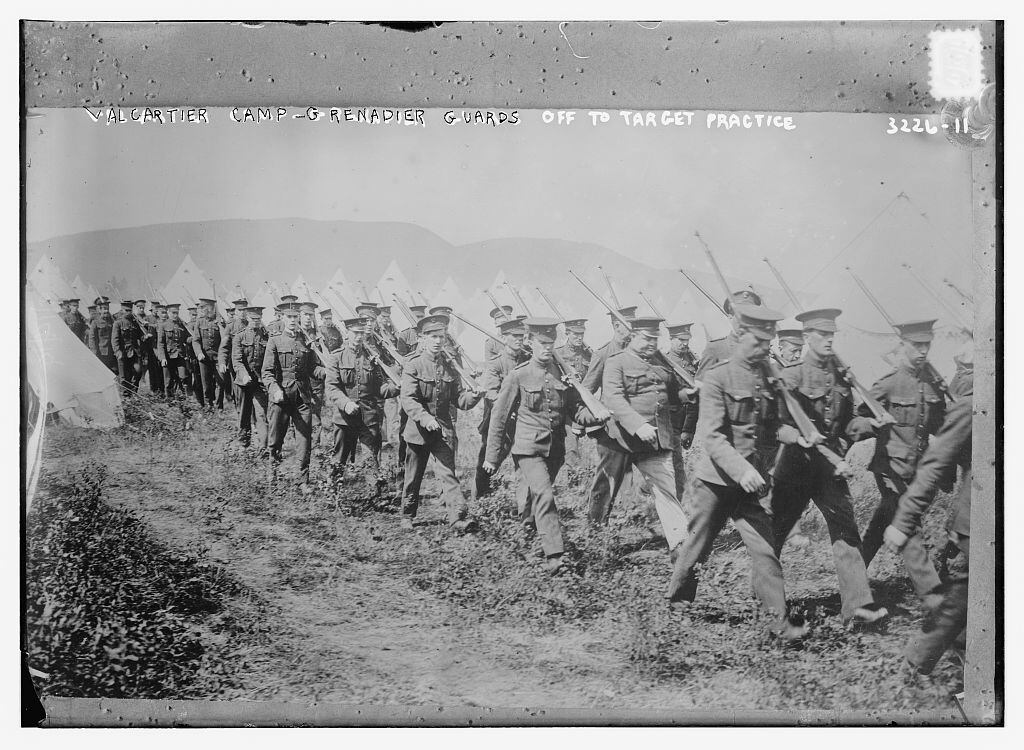

Born in Talmadge, Maine, on Jan. 29, 1894, William Henry Metcalf attended Waite Grammar School and was working as a barber when he enlisted in the 12th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, in Valcartier, Quebec on Sept. 23, 1914.

Metcalf shipped out to France the following month and transferred to the 16th Manitoba Regiment, 3rd Brigade, 1st Canadian Division, as a corporal.

After surviving the battles of Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele and Amiens, Metcalf was a lance corporal with the Military Medal and bar when the Allied forces launched their final offensives of the war.

On Sept. 2, 1918, Metcalf’s unit was assaulting the Drocourt-Quéant line at Cangicourt when it encountered heavy resistance on its right flank. Contacting a British tank, Metcalf led it against the enemy positions by preceding it in the open with a signal flag to make up for the poor visibility its crew was afforded.

Although repeatedly wounded by enemy fire, he guided the tank until a breakthrough was achieved and only then took cover to receive medical attention. He was hospitalized for nine months before receiving the VC.

After the war, Metcalf settled down in Maine as a garage mechanic. He died on Aug. 8, 1968, and in accordance with his last wishes, was buried in Maine soil overlooking the St. Croix River toward Canada.

On the same day Metcalf earned his Victoria Cross, another American was doing the same in the same area — but not in the same manner.

Bellenden Seymour Hutcheson was born on Dec. 16, 1883, and educated at Northwestern University Medical School.

He married a Nova Scotian, and on Dec. 14, 1915, he renounced his American citizenship to enlist in the 97th Battalion, 1st Ontario Central Regiment, Canadian Expeditionary Force, as a medical officer.

On the first day of the final British offensive on Aug. 8, 1918, he rescued multiple wounded British troops.

A month later, on Sept. 2, 1918, Hutcheson was attached to the 75th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, assaulting Dury, east of Arras. During the battle, he recovered numerous soldiers, including a gravely wounded officer for whom he elicited the help of British and captured German troops, then advanced under fire to rescue a wounded sergeant.

Having already earned the Military Cross, Hutcheson was awarded the VC for his actions on Dec. 14, 1918.

After the war, Hutcheson reclaimed his American citizenship to resume his medical profession in Illinois. He died in Cairo, Illinois on April 9, 1954, and is buried in Illinois.