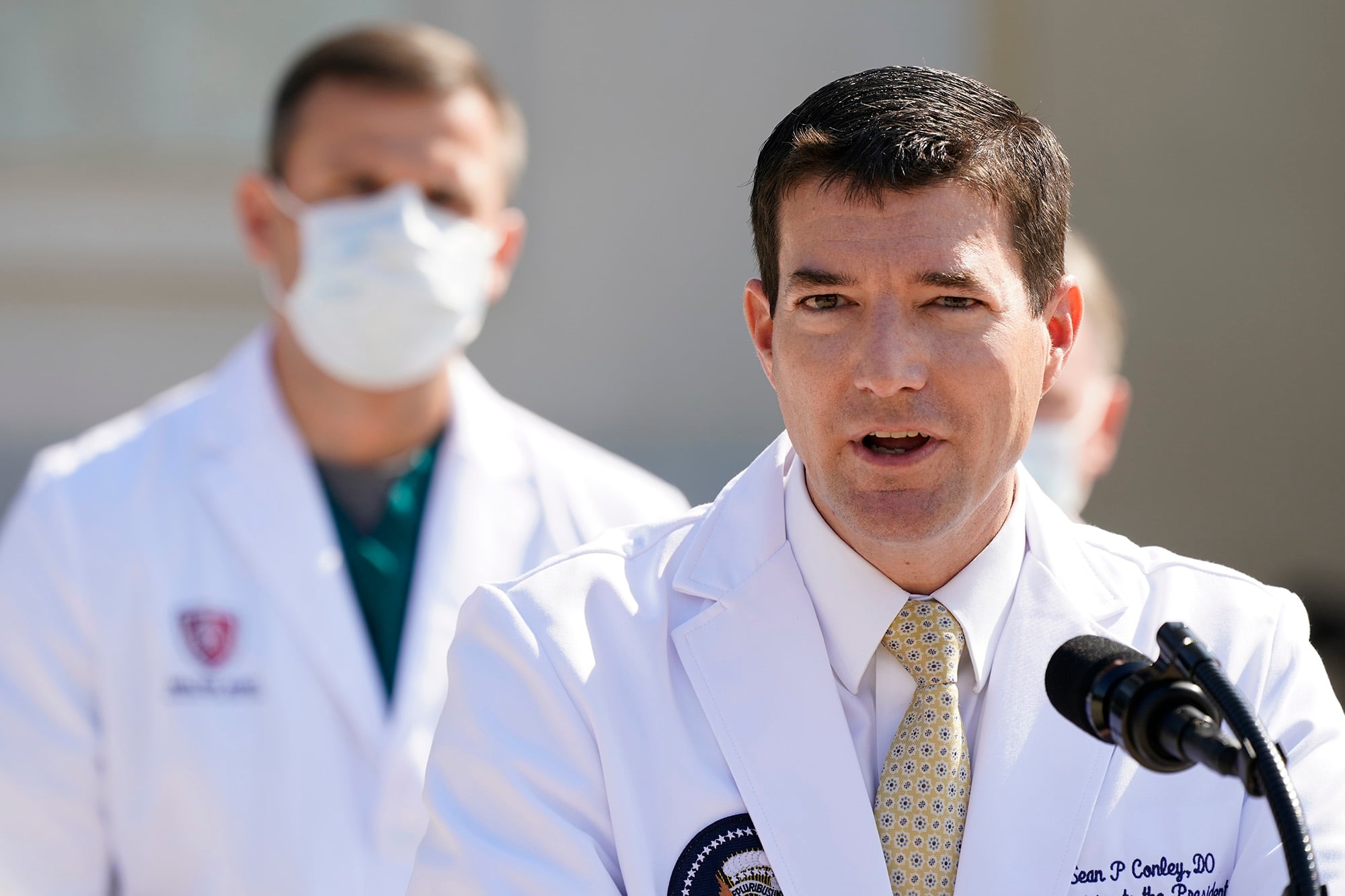

For the second day in a row, the Navy commander in charge of President Donald Trump’s care left the world wondering: Just how sick is the president?

Dr. Sean Conley is trained in emergency medicine, not infectious disease, but he has a long list of specialists helping determine Trump’s treatment at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

Conley said Sunday that Trump is doing well enough that he might be sent back to the White House in another day — even as he announced the president was given a steroid drug that’s only recommended for the very sick.

RELATED

Worse, steroids like dexamethasone tamp down important immune cells, raising concern about whether the treatment choice might hamper the ability of the president’s body to fight the virus.

Then there’s the question of public trust: Conley acknowledged that that he had tried to present a rosy description of the president’s condition in his first briefing of the weekend “and in doing so, came off like we’re trying to hide something, which wasn’t necessarily true.”

In fact, Conley refused to directly answer on Saturday whether the president had been given any oxygen — only to admit the next day that he had ordered oxygen for Trump on Friday morning.

It’s puzzling even for outside specialists.

“It’s a little unusual to have to guess what’s really going on because the clinical descriptions are so vague,” said Dr. Steven Shapiro, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s chief medical and science officer. With the steroid news, “there’s a little bit of a disconnect.”

Conley has been Trump’s physician since 2018 — and already has experienced some criticism about his decisions. In May, Conley prescribed Trump a two-week course of the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine to protect against the coronavirus after two White House staffers had tested positive. Rigorous studies have made clear that hydroxychloroquine, which Trump long championed, does no good in either treating or preventing COVID-19.

This time around, Conley is being put to an even greater test, trying to balance informing a public that needs honesty about the condition of the president with a patient who dislikes appearing vulnerable.

Dr. Stephen Xenakis, a psychiatrist who retired from the Army medical corps as a brigadier general, said Conley would be obliged to follow Trump’s wishes regarding what information about his condition is released publicly, as is true in any doctor-patient relationship.

But Conley as a military medical officer is bound to adhere to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which prohibits lying, he said.

A number of current and former military officials declined to comment on the record, referring all questions to the White House. But several said they were concerned that Conley’s efforts to spin a more upbeat characterization of the president’s current health condition is raising flags within the Navy about his credibility and the reputation of the Navy’s medical team. They said his admission that he tried to give an optimistic description of Trump’s condition may lead the public to question future information he or the other doctors provide.

They spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss internal conversations or because they are not part of the president’s medical team and therefore do not have details on his condition.

According to medical licensing records from Virginia, Conley graduated from the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine in 2006. Rather than having an M.D. degree, Conley is a D.O., or doctor of osteopathic medicine — a fully licensed physician but one that, according to the American Osteopathic Association, focuses more holistically on treating the “whole person.”

Conley went on to a residency in emergency medicine at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, Virginia, and served at a NATO trauma hospital at Kandahar airfield in Afghanistan.

A trauma expert isn’t required to be up to speed on respiratory viruses — but deciding to move Trump to Walter Reed meant Conley would be backed up by a team of critical care experts who specialize in pulmonary and infectious disease.

Several are Walter Reed staff, but the team also brought in Dr. Brian Garibaldi from nearby Johns Hopkins University, a well-known expert in acute lung injury who has cared for COVID-19 patients.

Garibaldi told a Hopkins publication over the summer that he had enrolled in a study testing if hydroxychloroquine could protect health workers — even as he said doctors must “resist the urge to give this medicine to everyone. We all want to do something to help our patients but sometimes doing something can be more harmful than doing nothing and I think we need to keep that in mind.”

What’s known about Trump’s current treatment: He was given an experimental antibody drug that most people could get only in a research study — along with a course of remdesivir, an antiviral, earlier than most patients.

Pittsburgh’s Shapiro, who is both a lung and critical care specialist, called those reasonable decisions: The idea is to help the body fight the virus early, before it triggers a lung-damaging inflammatory overreaction.

What Trump’s medical team hasn’t mentioned: Whether he’s getting blood thinners, which are being given to nearly all hospitalized COVID-19 patients to prevent virus-triggered blood clots that in turn harm the lungs and other organs.

And giving the steroid drug to a mildly sick patient disregards treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health and World Health Organization that say it’s only for people ill enough to need oxygen. For seriously ill people, research shows that once the virus has escaped the immune system, dexamethasone can tamp down the resulting inflammation and save lives.

“If they’re really talking about discharge tomorrow, and he really isn’t on oxygen,” Shapiro said, “then it’s more likely that the dexamethasone is just thrown in there as more one more thing that probably isn’t necessary and might not even be helpful.”

“The next few days are going to be key,” Shapiro noted.

AP reporters Lolita C. Baldor and Brian Witte contributed to this report.