Editor’s note: This commentary was first published in The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

“Hey, Eeyore, we need to do something big,” Jim Gover said, using my nickname since we couldn’t use our real ones in sonar for security reasons.

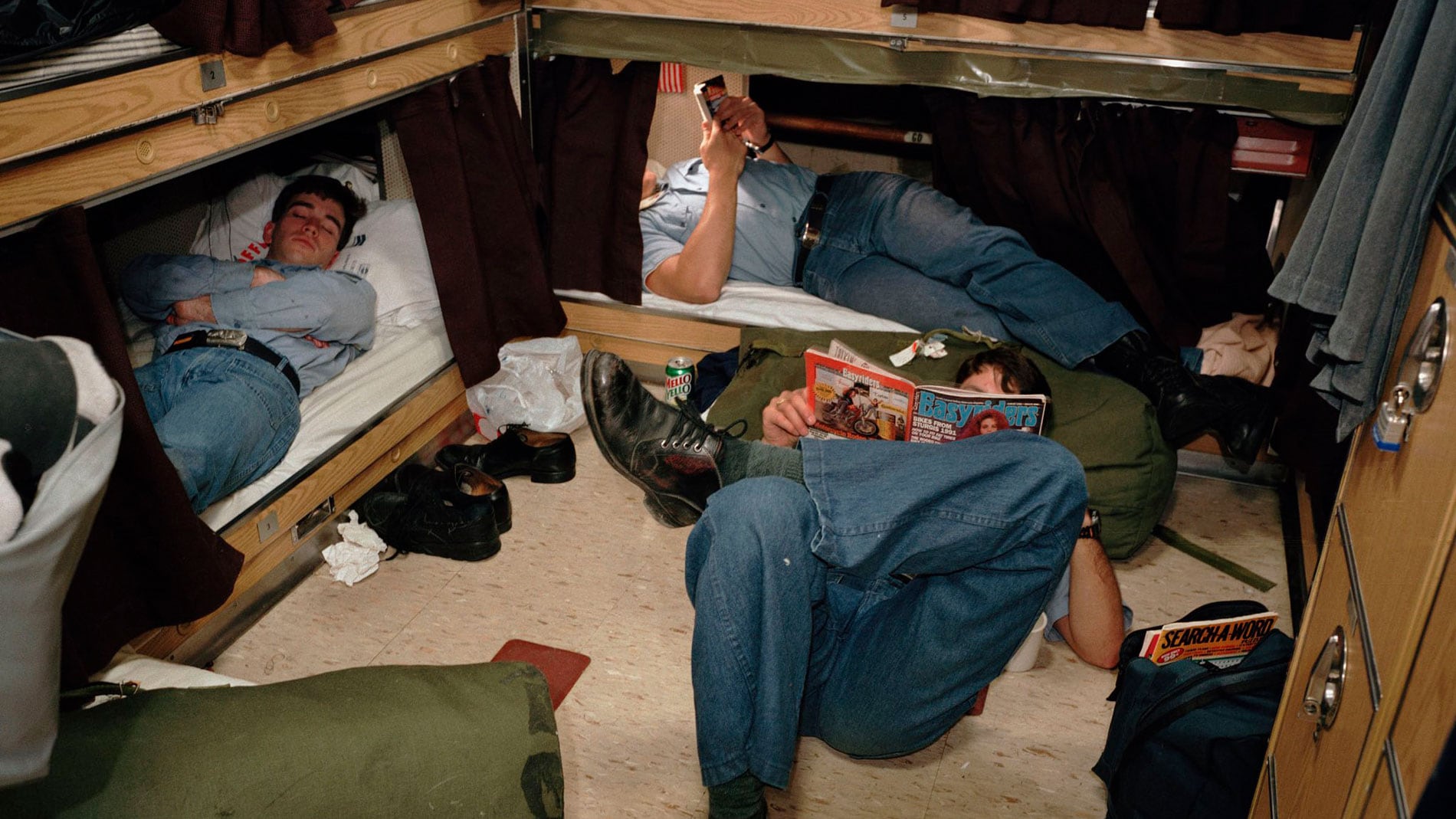

We were on day infinity of submarine patrol and my partner in mischief, Jim Gover, was about to get me in trouble again.

“We are 400 feet under the water in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with 24 Trident C-4 missiles pointed at the Soviet Union,” I responded. “Isn’t that big enough?”

“No, you idiot. I’m talking about something really important — a big prank.”

“Dude. We’ve been out to sea for seven weeks now. We’ve done all the usual pranks — the ‘mail buoy,’ ‘relative bearing grease,’ ‘water slug serial numbers,’ ‘blow the DCA,’ ‘feed the shaft seals.’ We even stole the executive officers’ stateroom door and replaced it with the door from the officer’s head. It doesn’t get much ballsier than that.”

Jim chuckled. “Yeah, the XO’s door heist was a lot of fun, but I think we can do better. Think big, man. How can we pull something off that would impact everyone on the crew and still be 100% safe? What’s something that touches everyone?”

“Easy,” I said. “Toilet paper.”

“Great. Let’s steal all the toilet paper and cause a shortage.”

Some things sound simple when you are sleep deprived and bored out of your mind on a slow watch. Executing them is far more challenging. We started small — just grabbing a few rolls and stashing them after each watch. Jim started spreading a rumor that the supply officer didn’t order enough toilet paper and we might run out.

Gossip spreads quickly in tight quarters with a small crew, and it didn’t take long until people were walking around with their own personal rolls of toilet paper. Jim and I chuckled with delight. It was already working! But our celebrations were woefully premature. Our plan was fatally flawed.

First off, the sub had plenty of toilet paper — enough for another 100 days at least, and God forbid we stayed out that long. Second, the toilet paper was stored in the chief’s quarters where the old goats jealously guarded it like dragons sitting on a mountain of treasure. Finally, and most importantly, we ran out of places to store it. Sure, hiding 20 or 30 rolls doesn’t seem that hard. But a submarine isn’t that big. Where are you going to hide 600 rolls? After about two weeks of effort, we realized the plan wasn’t going to work and spent the rest of patrol “reintegrating” the toilet paper into the ship’s supply.

But we couldn’t give up on the big idea just yet. Jim and I spent that next off-crew tossing ideas back and forth and finally we settled on FORKS! We hatched a plan to slowly and methodically steal all the forks on board.

Once we started our next patrol, I rounded up everyone in the sonar division and outlined the strategy. First, each person at the end of every pre-watch meal would slip their fork into the pocket of their coveralls instead of returning it to the scullery for cleaning.

Next, they’d bring the forks up to the sonar control room and stash them in a safe place. Five people per watch section and four watch rotations a day mean that we could conceivably steal 20 forks per day. By the end of the month, we’d have 600 forks in our possession! I wondered how many forks were on board, anyway — the crew numbered only 165.

We started the heist, but it was going at a glacial pace. Still, the great thing about forks is that they don’t take up a lot of space. We stored them in a toolbox in the Sonar Control Room. We hid them under a false bottom that was difficult to see in the darkened “blue room of doom.” After about a month, I took inventory and we had over 400 forks — but there seemed to be no shortage of them on the mess decks.

“Time to step it up,” I told the guys.

On mid-watch, when most of the crew was sleeping, I sent the sonar auxiliary operator to the mess decks on recon missions to steal a few extra forks. Each night they came back with an additional handful.

This went on for another week, and finally, Jim overheard the cooks yelling at the mess attendants: “What’s happening to all the Goddamned forks?!”

“I don’t know,” the hapless mess attendant said. “I just put out a bunch more last night and now they’re all gone!”

“We’re down to our last box,” the cook said. “You need to guard the forks!”

Now things were starting to happen. The cooks made sure the forks stayed in sight of someone on the mess decks. Rumors started flying among the crew and people started keeping their own personal forks and washing them in the crew’s head. Unintentionally, the cooks had made the problem worse — now the entire crew was hoarding forks.

Meanwhile, we continued our pace of thefts and probably added another 100 forks to our stash. This was great! We weren’t even to the halfway point of patrol and we’d stirred up a good fork panic.

Finally, the supply officer stepped in and replaced the remaining metal forks with plastic forks. Then he went to the XO and informed him of the problem. The XO, sensing a rat but not yet wanting to upset crew morale, decided to have every officer in the wardroom search the entire boat looking for the missing forks.

He divided up the boat amongst all the officers, gave them each a flashlight, and they spent an entire watch rifling through every locker, shelf, cubby, and possible hiding place from bow to stern.

I was on watch when the search team came into sonar. They tried — they even opened up the toolbox where we’d hidden the forks, but they didn’t notice the false bottom before closing it and moving on. Disaster averted; the prank was still alive!

Still, I knew the powers that be would regroup and our days were numbered. About this time, I wrote up a fake “plan of the day” and included in it an announcement on the disappearing forks that went like this:

Warning! All hands beware! A herd of renegade forks has escaped from the mess decks and is reported to be at large. Do NOT attempt to apprehend. These forks should be considered disobedient and unruly. If seen, any confrontation should be avoided and the “Fork Apprehension Rehabilitation Team” (FART) alerted immediately.

The crew had a good chuckle and everyone kept on using their personal forks or dealing with the plastic forks. The next Saturday was pizza night. Most of the crew came up for some pizza, and Jim and I were on the mess decks getting ready to go on watch. Now, most people eat pizza with their hands. But for some reason, the chief of the boat and the senior enlisted man on the crew decided to eat his pizza with a plastic fork that night.

Then it happened. His fork broke.

“Goddammit!” the chief of the boat bellowed. “Enough of this bullshit! I want the forks back NOW!”

Jim and I smirked at each other and suppressed our laughter. We knew the gig was up; it was only a matter of time until we paid the piper.

Neither Jim nor I ever announced ourselves as the originators of the prank, but everyone knew. It was always us.

We went on watch, and about an hour later, my boss, Jim Conlin, came into the sonar shack.

“If you return the forks now, you get amnesty,” he said. “I would advise you to do as such.”

And that is what we did. We loaded all the forks into a brown paper bag, and I had the auxiliary operator set them outside of the wardroom pantry. Once he returned, I placed an anonymous call to the mess decks to inform them that the forks had been miraculously recovered. It had taken nearly 50 days to pull off the prank, and it had affected everyone on the crew. Nobody was hurt, and it gave us all something to help pass the time.

A submarine patrol — like all military service — is long episodes of boredom interspersed with random moments of terror. Isolated for weeks at a time with no access to news or even letters from home, boredom set in pretty quickly, and we always looked for diversions.

Practical jokes filled that space and helped pass the time; they were a rite of passage. Jim and I staged a lot of practical jokes in our time together on the USS Nevada, but nothing would ever top the “Great Fork Heist of 1988.”

David Chetlain spent more than nine years in the Navy as a sonar technician. He qualified in submarines on the USS Georgia SSBN 729 and was subsequently a plankowner on the USS Nevada SSBN 733. He also served as the ship’s rescue swimmer and photographer. His last patrol was during Desert Storm in 1991. After completing submarine duty, David spent two years as a recruiter at NRD Portland where he finished college and took an early discharge. He has spent his entire civilian career in the software industry.

Tags:

funny military storiesfunny navy storiesbest military storiesbest navy storieslife on submarinesubmarine storiesopinioncommentaryIn Other News