When the opportunity presents itself, how can the U.S. and its allies not strike a common enemy? How are those decisions made, and who makes them?

It's questions like these and many more that confront audiences watching "Eye in the Sky," a film that follows the British military's mission to keep watch over enemy combatants defecting to al-Shabaab in Kenya. The operation cannot be carried out, however, without a U.S. Reaper — armed with two hellfires.

But the film, in a well-developed story line, doesn't plan to answer all of these questions; it conjures up more uncomfortable conversations.

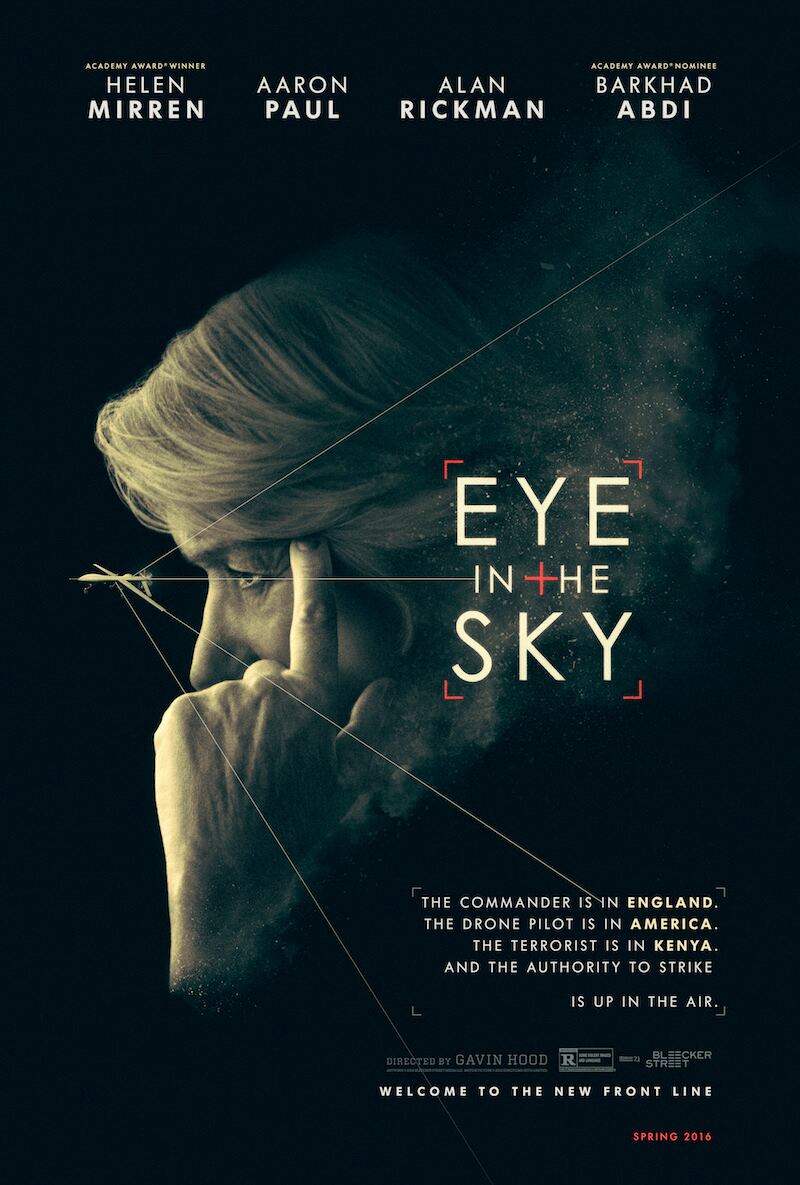

Air Force Times sat down on March 7 with "Eye in the Sky" director Gavin Hood. Before his movie career, Hood served a few years in the South African military. The film, which stars Helen Mirren, Aaron Paul, Alan Rickman, among others, opens in select cities on March 11.

Hood's comments have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q. How did you plan moving through each narrative to make sure everyone's story was told in an accurate way for viewers to understand who makes these decisions? Especially for audiences who may not have any idea what RPA pilots actually do?

A. We didn't want the film to preach or tell anybody what to think. We wanted to give points of view from people in different jobs and different relationships to this particular scenario. I hope that they are given some insight into the world of drone warfare, which is more and more where we are going. ... And if you don't know much about it, you've heard about it in the abstract.

Q. Did you consult members of the military or the Air Force when making "Eye in the Sky"?

A. I think it is important that the movie has an objective voice, but I got great assistance for many people within the military. I spoke to colonels, I spoke to military intelligence officers, I spoke to drone pilots. We had a ... remotely piloted aircraft pilot who also used to fly F-15s and F-16s. He flew fighter jets for 10 years before moving into RPAs. He is now in the reserves so he is still flying. ... What you want for your actors (Aaron Paul, Phoebe Fox) is for them to have the advice of an expert to make sure that they have got all of the technical flying information correct. ... We had a British military adviser for Helen Mirren (who plays Col. Katherine Powell). I also spoke to people that ran the geospatial institute in Hawaii.

Q. Why did you show in such details the approval process for an airstrike?

A. I spoke to people who train drone pilots. The line that Aaron Paul (2nd Lt. Steve Watts) gives, "I am the pilot in command responsible for releasing this weapon, I will not release this weapon until you read me a new CDE [Collateral Damage Estimate]" is an absolutely accurate line to train the pilots because drone pilots, not just as the person who pulls the trigger, have the right to confirm that that order is legal if they doubt it. ... If they follow an illegal order, they can be charged with a war crime. So the stakes are high for them. But once it's confirmed for him that that order is legal, if he doesn't follow it, he would be court-martialed. ...They have to follow orders provided those orders are legal. And how do you, as a young pilot, make that distinction? Tremendous pressure to know because if you disobey an order that is a big deal.

Q. What kind of technologies are presented in this film?

A. There are basically three drones portrayed. There is the Reaper ... then there is the Hummingbird. We changed our design to just look a little different [from the actual Nano Hummingbird drone], but the idea is of a bird that flaps wings and has a camera on it. ... There is an Air Force video about micro aerial vehicles ... called M.A.V.s. The Beetle drone. The problem in the movie is actually just battery power because the smaller they get the more powerful the battery needs to be to generate flight and transmit high-def[inition] video. So the batteries are running out, and that's part of the frustration. The real question is not are these little drones real. The question is how quickly is our movie out of date because of the little drones can now being armed.

Q. Why did you choose Kenya as the setting for this film?

A. Traditionally warfare has always been defined by geographical space. The conflict zone, once we are in the conflict zone, once we've entered a war, the laws of war that we've traditionally had govern what happens within the theater of war. ... The tricky thing we are in now is we are now also hunting using drones, hunting in areas with whom we have not declared a war, so in "peaceful" countries. Referring decisions through the chain of command would not be insane within [Afghanistan] as it would be in Yemen or Kenya or Somalia or areas where there is not a ground conflict that has been fully declared...To do a drone strike in an area of conflict like Afghanistan or Iraq is a different story to telling a story about a potential strike in a "friendly" country.

"Eye in the Sky" opens in select cities March 11.

Photo Credit: Bleecker Street Media

Q. How does the conversation surrounding modern warfare develop in this film?

A. The way warfare is waged is changing so rapidly both in terms of the way we fight war and the way our enemies fight war. But the laws of war are in need of a rethink, and there are people lobbying for certain approaches from different points of view and so I think ... it helps us to acknowledge that one of the reasons we wanted to make the film is to bring a kind of visceral, visual language to what can sometimes be a very academic debate. ... I would hate for any of our viewers to think that this director has solved the problem of modern warfare. I resubmit that I genuinely don't, and that is why I found Guy's [Hibbert] script so exciting and wanted to make the film because it allows the audience to be the jury. It doesn't tell anyone what to think.

Q. What do you want U.S. airmen, the U.S. military as a whole, to take away from this?

A. What I like about Aaron Paul's approach as a pilot, and, I have met many pilots who do have this approach and some who don't, is that he understands that he is taking human life. [Some] describe the targets as "bug splats" and they are very crass in the conversation about the loss of life. ... For me, it is important that those pilots understand that speaking like that about their fellow human beings even if they are an enemy is a recruitment tool for the enemy. The way we fight and the way we speak and the way we describe them matters from a strategic military point of view, not just from a "touchy-feely" point of view. I believe we have to win this war. [But] we should do so without dehumanizing the enemy.

Oriana Pawlyk covers deployments, cyber, Guard/Reserve, uniforms, physical training, crime and operations in the Middle East, Europe and Pacific for Air Force Times. She was the Early Bird Brief editor in 2015. Email her at opawlyk@airforcetimes.com.