The most important and far-reaching decision in the FY21 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) is whether the U.S. Space Force (USSF) will adopt a naval rank structure for officers. If Congress agrees, it will begin the service’s great cultural shift necessary to carry America’s values boldly into space. If Congress punts, the service will continue meandering aimlessly while touting baffling trivialities such as being “born digital” to an increasingly disinterested public.

At least some people in the USSF knows that Americans find space exciting. Recruiters have done a great job capitalizing on this with their slogan “Maybe your purpose on this planet isn’t on this planet.” However, the difference between the USSF’s romantic marketing and it’s toxic combination of ignorant and terminally boring “vision” has confused the public.

William Shatner undoubtedly spoke for many Americans when he asked in a tweet if the USSF really planned on not calling Space Force ship commanding officers captains. Over 7,000 people liked Shatner’s tweet, including both Sen. Ted Cruz, chairman of the Aviation and Space Subcommittee, and Congressman Dan Crenshaw, who is championing a bipartisan House amendment calling for Navy ranks in the U.S. Space Force. That House amendment got a major shot in the arm when William Shatner elaborated on his tweet with a popular culture perspective in the Military Times.

The evolution of a tweet into a deceptively penetrating essay in an independent and reputable military newspaper breathed new life into a debate not just among military professionals and science fiction fans, but nationally among people from all walks of life. Shatner instigated a slew of articles on military culture and vision, and reinforced others written earlier dealing with space and the American psyche. Shatner brought the public into the on-going two-year debate about USSF ranks muffled because of a service corporate culture that has not historically valued dissenting perspectives.

Retired Air Force space officer Timothy Cox’s essay supporting a slightly modified Crenshaw rank structure is pivotal for its honesty, logic, and courage in declaring the USSF broken — comparable to former Acting Air Force Secretary Matt Donovan’s essay that ended the Air Force’s “malicious compliance” opposition to the USSF’s establishment. Cox’s proposal integrates Shatner’s concerns with Crenshaw’s proposed ranks to support the USSF’s mission within the service’s newly chosen three-echelon command structure. Crenshaw’s and Cox’s proposals fit the USSF’s own preferred organizational structure like a glove, and are critical to evolving the USSF into what the nation both wants and needs. Exploring how these proposed ranks fit elegantly into the USSF’s command structure will quickly explain why.

The admirals — The field commands and the “fleet”

During the Age of Sail, a fleet would be split into thirds — the van (front), the middle, and the rear. The USSF’s top-level command structure bears a strong resemblance to a classic naval fleet. The USSF’s Office of the Chief of Space Operations (OCSO) oversees three echelons (layers) of command that comprise, from highest to lowest: the Field Commands, the Deltas, and the Squadrons. OCSO houses the two four-star officers: the chief of space operations and the vice chief of operations. Under the bipartisan House amendment, these two officers are the “leaders of space” would become full admirals — a term derived from the Arabic Amir-al-Bahr (leader of the sea) — and oversee the manning, training, and equipping of the entire USSF and directly command the Field Commands.

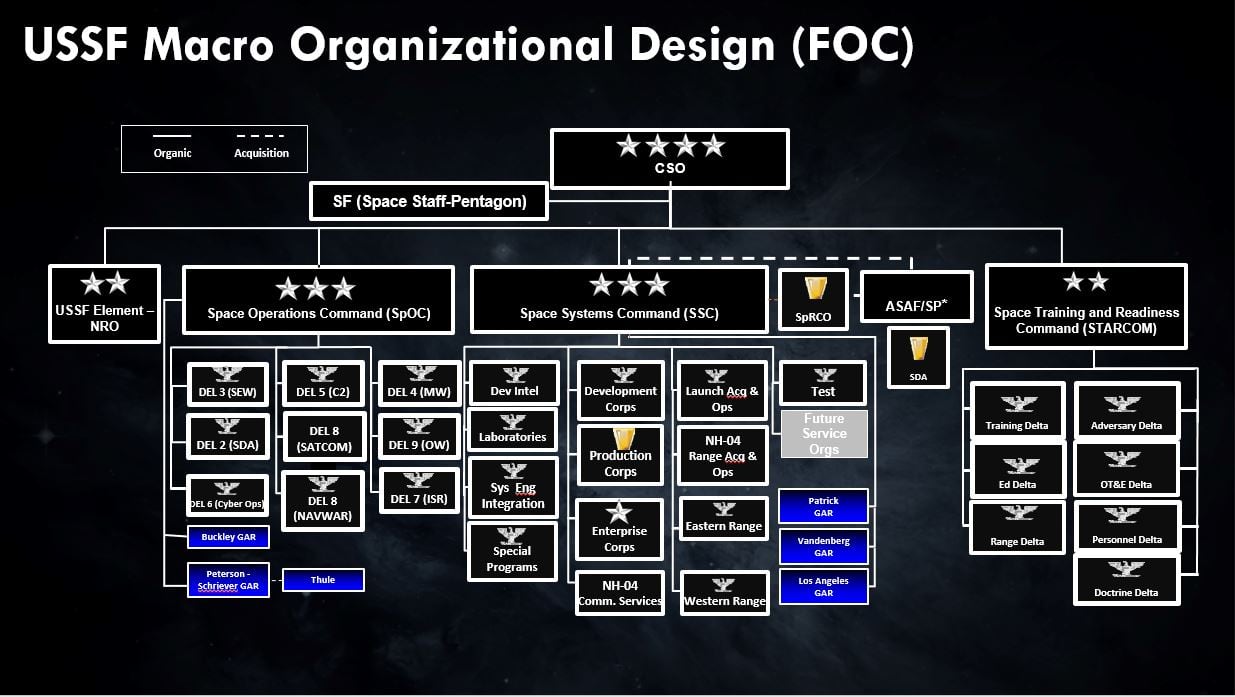

The two proposed “senior” Field Commands are aligned to broad, enduring missions. The Space Operations Command (SpOC) is the “primary force provider of space forces and capabilities for combatant commanders, coalition partners, the joint force, and the nation.” Once authorized, the Space Systems Command (SSC) will develop, acquire, launch, test, and sustain and maintain USSF space systems. Under the House amendment, the three-star flag officers overseeing SpOC and SSC would convert to vice admirals.

The two envisioned “junior” Field Commands support the senior Field Commands' activities. The Space Training and Requirements Command (STARCOM) and the U.S. Space Force Support Element to the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) would be commanded by two-star flag officers, who would be retitled rear admiral under the House amendment. Slated to be established in 2021, STARCOM would “train and educate space professionals, and develop combat-ready space forces to address the challenges of the warfighting domain of space.” The USSF Element – NRO is proposed to support USSF personnel assigned to the NRO.

The USSF structure and organization has adopted much of the naval model in which the admiral’s flagship, in this case the OCSO, would be in the middle third of the fleet to best communicate with both his fleet’s van — in this case the senior Field Commands conducting operations, and rear — the junior support Field Commands responsible for readiness and support. In the USSF’s fleet model, the admiral’s deputy vice admirals would command the operational van while the USSF’s rear admirals command the rear support branches. Crenshaw’s ranks structure is a natural fit, but it does not apply to only admirals.

The captains — At the head of the deltas

The USSF command structure has fewer one-star officers who will likely serve as Field Command deputy commanders or as staff officers. Since they will not be within the USSF’s “fleet” structure, the bipartisan House amendment’s call for rear admiral lower half needs to be modified to commodore, an honorific title once used for senior captains commanding more than one U.S. Navy ship. The USSF can utilize commodores, as a senior captains, to reinforce the middle commands, the deltas, which report directly to Field Commands.

Deemed critical by USSF leadership, eight permanent deltas are grouped by specific missions such as Missile Warning, Orbital Warfare, and Command and Control. Under the House amendment, the O-6 officers leading the deltas would become O-6 captains. Rooted in the Latin term caput (head), captains were originally as ship’s masters in charge of fighting and sailing. These ranks reinforce the identity of the delta leader because, over time, both commodores and captains will probably command deltas, depending on the importance of the mission and organizational size responsible for tasking assigned squadrons.

The commanders — Masters of the squadrons

Squadrons are the USSF’s small organization and command echelon “focused on specific tactics” or operating specific systems. USSF squadron commanders are led by O-5 commanders, who are responsible for all squadron operations in similar ways the naval “Master and Commander” is a ship’s commanding officer and serves as sailing master, responsible for every major task. The House amendment formally recognizes the O-5 squadron commanders with the commander rank by reinforcing this leader’s grade duties.

Similarly, O-4s in the USSF will often be operations officers, who direct lieutenants to squadron commanders, and some may even command smaller squadrons. The House amendment’s conversion of majors to the rank of lieutenant commander reinforces the continuity of the squadron commander position just as well as the USSF’s more senior ranks.

| Grade | Air Force rank | Crenshaw rank* | Space Force command level |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-10 | General | Admiral | Headquarters and Field Command |

| O-9 | Lieutenant general | Vice admiral | Headquarters and Field Command |

| O-8 | Major general | Rear admiral | Headquarters and Field Command |

| O-7 | Brigadier general | Commodore* | Delta |

| O-6 | Colonel | Captain | Delta |

| O-5 | Lieutenant colonel | Commander | Squadron |

| O-4 | Major | Lieutenant commander | Squadron |

| O-3 | Captain | Lieutenant | Spacecrew |

| O-2 | First lieutenant | Vice lieutenant* | Spacecrew |

| O-1 | Second lieutenant | Ensign | Entry |

| * Cox variant |

The lieutenants — Crew commanders and fighting experts

Below the lieutenant commander, the junior officer ranks of lieutenant (O-3), lieutenant, junior grade or the Cox variant of vice lieutenant (O-2), and ensign (O-1), round out the House amendment proposal for Space Force officers. Derived from French word for “placeholder,” a lieutenant serves in lieu of a ship’s captain and was often referred to as “lieutenants commanding.” In the USSF, lieutenants will often get their first chance of command as spacecrew commanders, leading spacecrews operating the space systems “in lieu” of the squadron commander, but invested with his authority, on a day-to-day basis. USSF junior grade officers will often be the spacecrew’s technical experts, focused on developing their tactical space expertise. However, they will often be capable of serving as crew commanders “in lieu of” lieutenants. Therefore, when considering the House amendment it may be useful to rename O-2s to vice lieutenants to distinguish between the roles and responsibilities of O-2s and O-3s, since in most of the services an O-3 promotion is considered a significant increase in responsibility and prestige.

The officer rank, ensign, derives from the Norman enseigne (flag) was used as a U.S. Army rank until 1814 to designates an infantry regiment’s lowest ranking officer. The U.S. Navy later adopted the rank in 1862 for “passed midshipmen,” often fresh from the Naval Academy. Ensign is an appropriate Space Force rank since it has been widely by Army, Navy, and Coast Guard history as a newly commissioned officer.

The bipartisan House-approved Crenshaw system for USSF officer ranks is neither nonsense nor service parochialism. On the contrary, it naturally supports the USSF’s organizational construct and Americans' expectations. Ignoring the amendment by downplaying current realities, the vision of how the USSF will need to evolve to meet future threats and opportunities, and allowing the USSF to muddle along with an Air Force culture will play into the hands of those critics who never supported the idea of the USSF to begin with and wish to keep it grounded. Without a doubt, the bipartisan House amendment would have gone unnoticed by the public, maligned by Air Force lobbyists, and killed without reflection had it not been for the Military Times publishing Shatner’s editorial and continuing to let the debate play on its pages. This essay continues that debate and provides the Department of Defense and Congress an opportunity to reach an understanding in order to develop a positive solution.

Brent Ziarnick is an assistant professor of national security studies at the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Air University, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Editor’s note: This is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.