Air Force Lt. Col. Derek Bright’s children were out of their home at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, for so long that Fairfax County school officials considered them homeless. Displaced for 87 days while their home was treated for mold, the kids qualified for the school district’s free lunch program.

Ashley Fischer and her Navy chief husband lived in a hotel off post near Fort Belvoir, then in a temporary house, after mold was found in their home — and while their 3-year-old son has been undergoing treatment for brain cancer.

Raven Roman and her family are living in their third home in a year and it’s not because of change of station moves for her husband, an Army chief warrant officer. They’ve been displaced from their home at Fort Belvoir twice because mold and other problems have affected their health.

“We decided to move off post. We can’t put our children at risk,” Roman said. But the move off post cost them $8,000 out of pocket, she said.

“We’re going through the second round of throwing our personal belongings away,” because of mold contamination.

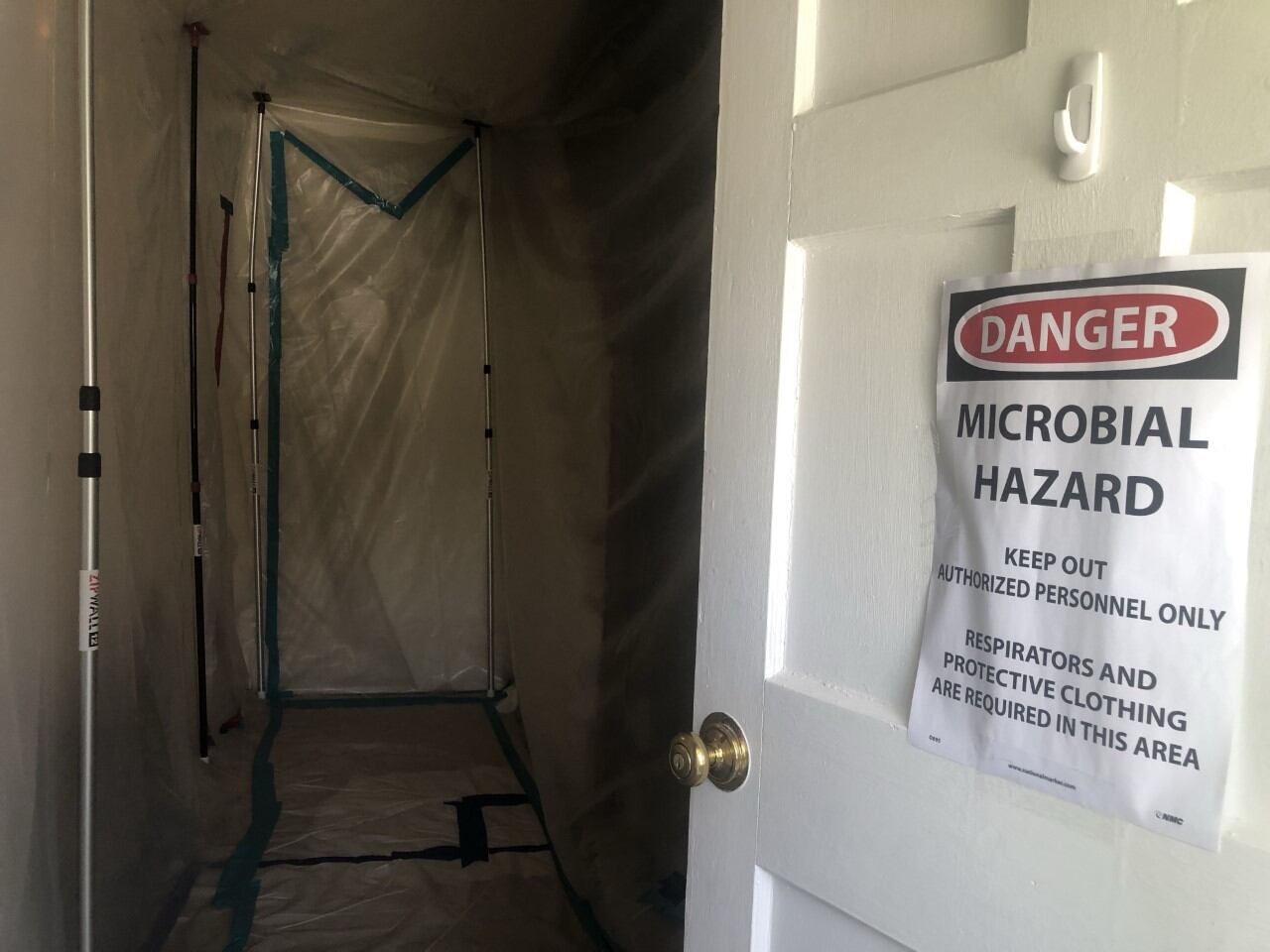

As the problems with mold and other health and safety issues in military privatized housing have come to light, officials in the services and in privatized housing companies have vowed to address the problems quickly. But in some cases, that means a family has to leave the home while the company remediates the problem, which might take a week — or months.

RELATED

The problems at Belvoir are a microcosm of similar issues across the country, affecting members of all the military branches.

At Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma, for example, residents have been complaining for years about the lousy housing conditions and their frustration with the lack of progress in getting problems fixed. Like many other Air Force bases, Tinker has had a significant mold problem in its privatized housing, but more recently, problems with asbestos and faulty firewalls in the homes have come to light.

In September, base leaders informed residents that a subcontractor to Balfour Beatty Communities had potentially disturbed asbestos while replacing floors in about 20 houses.

“The subcontractor executed the work without appropriate safety precautions and did not notify residents that proper safety precautions had not been taken, creating possible risks to residents,” said Col. Paul Filcek, commander of the 72nd Air Base Wing, in a news release.

Thirteen families were displaced to hotels, at no cost, while work to make the houses safe again was completed, according to the Air Force.

Shortly after the asbestos discovery, Oklahoma Sen. Jim Inhofe, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and then acting Secretary of the Air Force Matt Donovan visited the base to learn more about the problem.

RELATED

They also delivered an ultimatum to Balfour Beatty, the company that built and manages the homes: Deliver a plan for fixing all the problems within 90 days.

The myriad problems at Tinker with mold, firewalls and now asbestos have taken a toll.

“These families are being displaced for weeks, sometimes months … it’s awful with little children,” Air Force wife Janna Driver told KFOR-TV in Oklahoma City.

She, her husband and their 4-year-old twins have all suffered health problems and have had to move several times since their base house flooded and became infested with black mold.

“I get that they are being investigated,” Driver told the television station. “But it’s just not happening fast enough, and our military families are suffering tremendously because of it.”

While no one, least of all the families themselves, wants them to stay in unsafe houses, the delays in returning home can involve whole new levels of frustration. More, there’s inconsistency in how the families are treated in this displacement process, from base to base, company to company, and even sometimes on the same installation, according to families and advocates.

“All we’re asking for is standard operating procedures, transparency and accountability,” said Roman. Families also need information about navigating this complex, difficult process, and they need open lines of communication, she said.

Crystal Cornwall, executive director of the Safe Military Housing Initiative, is calling for “clear directives and polices that are followed for displacement, to include [Basic Allowance for Housing] rent reimbursement, food cards, and remediation or replacement of household items.”

“Displacement in and of itself is a huge inconvenience to families financially and within their everyday lives,” she said. “They have to figure out bus routes, how to get their kids to school, how to pay for the expense of eating out, gas. …”

Bright said he’s seen differences in how his and other families are treated at Fort Belvoir, compared to his previous assignment, Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, where he was also displaced because of mold. There, the housing company, Hunt, was better about communicating with residents and more honest about disclosing and addressing problems in the home. “It’s not right, and it’s not getting better. It’s getting more confrontational,” he said.

There are inconsistencies in how fast companies make decisions about remediation; whether families should leave the houses; what kinds of living expenses are paid, and whether families have to continue to pay rent when they’re out of a base house, said Darlena Brown, an Army wife who is founder and president of the Military Housing Advocacy Network. She’d like to see the service branches adopt a system similar to the family readiness groups, with true advocates working on behalf of military families to deal with housing issues.

‘Unacceptable’ displacements

Military leaders are aware of the inconsistencies in policies relating to displaced families.

“We’re working to be collaborative in the services, because we’d like it to be the same across the board,” said Gen. Gus Perna, commanding general of Army Materiel Command, noting that service members often live on an installation belonging to a different service branch, and everyone needs to clearly understand his or her rights.

The Army is tracking every displaced family — 1,722 since February, how long they’ve been displaced and when they move back in, he said. But that’s just the first step. Next, Perna said, is “the accountability … that they never should have been displaced to begin with; the standardizing of what we give them so they know their rights; and getting them back into their homes.”

He said he’s made it clear to housing company CEOs: Having problems that result in displaced families is unacceptable. He’s told them, he said, that he appreciates that they are providing some benefits for displaced families, but that’s only “mildly interesting.”

“When you can’t sit down, when you can’t sleep in your bed, when the lights aren’t the way you want them, when your children’s closets are their suitcases, it’s unacceptable. Unacceptable. So I appreciate you’re paying for this and you’re doing that, but it’s unacceptable to the end state we’re trying to achieve.”

The newly formed Military Housing Association, a coalition of five of the most active companies in the military housing public-private partnerships, declined to comment on whether the companies are working together to look at the procedures for helping military families who are displaced, and determining what is fair to the families and what is fair to the companies.

Because these lengthy displacements for health and safety reasons are relatively new, policies are evolving.

“This a relatively new area, as it was not common to have to displace residents over the past 12 years,” said Ron Hansen, president of Michaels Management Services. “We started at paying for hotels if a resident had to be displaced. Our assumption was displacement would be around a week.”

But as the numbers of displaced families and time of displacement increased, he said, Michaels and Clark Realty have been developing new policies, which are not yet formalized.

Who pays for what?

Generally, the companies are making arrangements for families to live elsewhere and are paying for a hotel or other living arrangements.

In some cases, the company no longer requires the family to pay rent — equivalent to the service member’s Basic Allowance for Housing. Sometimes the company charges prorated rent.

But that’s not always the case, and it’s not the expectation of the services.

Army, Air Force and Navy officials said that when the privatized housing company is providing temporary accommodations, the resident is still responsible for paying rent to the company — the amount of their BAH. “Oftentimes, the project owners will also provide some rent concession to the resident to offset the inconvenience,” said Air Force spokeswoman Laura McAndrews.

It may vary within the company, too. “Reimbursing BAH as a result of displacement is managed on a case-by-case basis, depending on multiple variables,” said Alisa Capaldi, spokeswoman for Corvias, which manages 26,000 homes across 13 installations.

Some companies pay per diem expenses or provide some reimbursement; others don’t. Some have paid for moves off the installation, others don’t. There can be differences between what one housing company manager offers families and what another manager offers families in another community on the same base.

In a hotel, even with a small kitchenette, it’s often difficult to cook, so expenses like eating out and extra gas add up, said Fischer, the Navy wife, especially for those who have been in a hotel for 100 days or more.

Once school started at Fort Belvoir, the Brights, the Air Force family, had to borrow school clothes from friends because their belongings were locked in their home, under remediation.

“We couldn’t get to our clothes,” Derek Bright said. “We can’t go and spend hundreds of dollars on clothes we already have.”

The Brights moved their children and chocolate Labrador retriever into two hotel rooms July 17, a week after their fifth child was born. The other children are 9, 7, 5 and 3. They were later moved into a townhouse, but later had to move out because of mold there, too.

But Bright said he is concerned about other families. Most of those displaced at Belvoir are E-6 and below.

“It’s absolutely the lower ranking enlisted families who are suffering the most,” said Brown, president of the advocacy network. “And they don’t have a voice.”

Unless there’s language in a tenant’s lease agreement that specifically addresses this, a resident may seek reimbursement for housing-related expenses by filing a claim with their renters insurance company or by filing suit in any court that has jurisdiction, according to Scott Malcom, spokesman for the Army Installation Management Command. But insurance companies providing renter’s coverage do not cover mold damage.

What about damaged belongings?

A sticking point for families is whether a company pays anything for replacement of belongings that have been ruined by mold and can’t be salvaged.

Until recently, Sgt. 1st Class Shannon Elliott’s family had been at an impasse with Fort Hood Family Housing regarding mold damage to their belongings, which remain in the second of three houses they lived in at the base. Because Elliott’s wife, Maureen, suffers from multiple auto-immune disorders, extreme care must be taken and some items are unsalvageable.

Lendlease officials declined to comment on its policies, saying in a statement, “As a matter of policy, we do not comment on the private lives of our residents.”

Fort Hood spokesman Tom Rheinlander said the private company hires a third-party consultant to assess and reimburse damaged household goods.

Corvias works with residents to ensure belongings are properly cleaned or replaced if necessary, said spokeswoman Alisa Capaldi.

When a resident claims that property must be disposed of because of mold, Michaels Management Services offers to specifically test and clean the items, said Ron Hansen, president of the company. If the resident believes cleaning is not acceptable and wants full reimbursement, the company looks at dispute resolution.

The local manager has the authority to resolve reimbursement on obvious items and reasonable requests, he said.

Is it safe to return to the house?

When the remediation is done, there are questions about how effective it is and whether it’s safe to return.

In August, commanders at Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi met with officials from Hunt Companies, the contractor in charge of base housing there, and angry residents to address problems they’ve faced there, including recurring mold. The residents had accused Hunt of failing to improve poor living conditions.

Col. Paul Fidler, deputy commander of the 81st Mission Support Group, said initial meetings about housing problems were filled with “very high emotions.” But the contractor now has a “Moisture Remediation Plan” which the support group oversees, and follow-up meetings were much better.

“It’s everybody’s question. What is considered safe? What do they do to make sure the family is safe coming back into the home?” said Roman, the Army wife.

The Romans had extensive mold in their first home at Belvoir, so the company moved them to another home in 2018 and paid for the move. About five months later, they found mold in the second home. They were moved to a hotel for 10 days, then back into the house. “We got a clearance report saying the home was good to go. But the main issue, the elevated humidity, was not addressed,” she said.

“We felt we couldn’t do it anymore. We didn’t feel we could put our children in another home on base,” she said. Two of their three girls had had pneumonia at the same time, and both had been getting sick with chronic upper-respiratory conditions.

So, their third house in a year’s time was a house in the civilian community — a move that cost them about $8,000 out of pocket.

Col. Greenberg, Fort Belvoir’s garrison commander, said families shouldn’t go back into their homes until everything is fixed. His command team reaches out to displaced families periodically to make sure they’re getting what they need and that they are getting the right information from the company about the status of their home. The command team reviews the status of displaced families each day with the company, he said.

Before the family returns to the home, the company’s quality control looks at the house to make sure the work is acceptable, and a quality assurance team from Fort Belvoir checks the house, he said.

At Fort Hood, the company follows state regulations, which include a mold assessment consultant and mold remediation contractor licensed in the state of Texas. After the work is completed by the remediation contractor, the assessment consultant inspects the work, according to spokesman Tom Rheinlander.

Corvias hires qualified professionals to respond to residents’ environmental concerns and they conduct post-remediation evaluation, according to their spokeswoman. “Typically, this work is verified by both Corvias’ maintenance team and our Army and Air Force partners at each installation,” said Alisa Capaldi.

What the Air Force is doing

On Oct. 2, Donovan met with Defense Secretary Mark Esper, the Army and Navy secretaries, and privatized housing project owners to assess the progress in reforming the Military Housing Privatization Initiative.

The Air Force is working five major lines of effort to address the health, safety and quality concerns of service members and families living in privatized housing.

♦ Empowering residents: In May, Air Force leaders established the Resident Hotline, a 24/7, toll-free helpline. The call center has assisted 45 callers.

The services have also joined together to develop a Resident Bill of Rights, and solicited feedback from service members and their families early this summer. A final draft is expected soon.

The Air Force is also working to establish resident advocates at its installations and working with contractors to implement automated work-order systems with greater transparency for service members.

♦ Improving oversight: The service is also in the process of hiring additional personnel at several bases to provide increased oversight, including Tinker and MacDill Air Force Base in Florida. Several bases were provided in April with resident construction managers, experienced in residential construction and mold remediation techniques.

♦ Integrating leadership: According to Air Force officials, commanders conducted 100 percent health and safety checks in 2019. The service is also negotiating with project owners to restructure the performance incentive fee plan, to allow for increased commander and resident input in the fee award.

♦ Improving communication: In March, the Air Force issued a letter to project owners defining its position on the use of nondisclosure agreements, after discovering improper use of the document at several installations. It has also identified and shared best practices by project owners across the housing portfolio.

Air Force leaders now are looking at adding questions to the housing survey to more accurately gauge the climate of each base’s housing program.

♦ Standardizing policy: The services are working to develop common leases, and have provided guidance on availability of legal assistance to residents. It is also revising annual site visits to better gauge the health of the housing program of each individual base.

At places like Forts Belvoir and Hood, Keesler and Dover (Del.) Air Force bases and Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington, some military members and spouses have stepped up as advocates — trying to provide information and resources to families to help them make decisions and help them in their discussions with housing companies.

Ashley Fischer is one of them. Her family’s displacement happened during an already stressful time. In December, they learned that their son Rhett, now 3, had brain cancer. He then began chemotherapy sessions and other treatment, with two to three trips a week to Children’s National Hospital in Washington. They discovered the mold in June.

Their two older children, ages 12 and 7, ended up staying with her parents the whole summer because of the displacement. “It robbed them of summer time with mom and dad,” she said.

“Ashley has really done a lot of great work trying to bring the problems we’re having here at Belvoir to the forefront,” said Bright, the Air Force officer.

“She’s been working with the garrison commander and the company. She’s a strong advocate for families who are displaced, who say, ‘Oh my God, what just happened to me? I don’t even know what to ask for or what to expect,’ ” he said.

Senior reporter Courtney Mabeus contributed to this report.

Karen has covered military families, quality of life and consumer issues for Military Times for more than 30 years, and is co-author of a chapter on media coverage of military families in the book "A Battle Plan for Supporting Military Families." She previously worked for newspapers in Guam, Norfolk, Jacksonville, Fla., and Athens, Ga.